Douglas Coupland at MOCCA (Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art, 952 Queen West) to April 19 and the ROM to April 26, . 416-395-0067. See listing. Rating: NNNN

Douglas Coupland is back again with more shoulder-shrugging digital anomie for the 21st century in his big MOCCA retrospective.

It features a smorgasbord of works from a visual arts career that’s gathering steam on the heels of his literary success. He plunges us once more into his essential medium, best described as Canadiana at a remove. The work is diffident and glib, and it conveys the basic gist of his oeuvre: we are all over-saturated and alienated and slightly bored, and beneath this boredom lurks a darker current we can’t bring ourselves to face.

As the world becomes more digitally accessible and globally connected, he seems to say, it also becomes flatter, weirder, glossier and more banal. By straining this message even further through his self-effacing Canadian sensibility, he leaves us with something akin to Duchamp unleashed at Vancouver Mall.

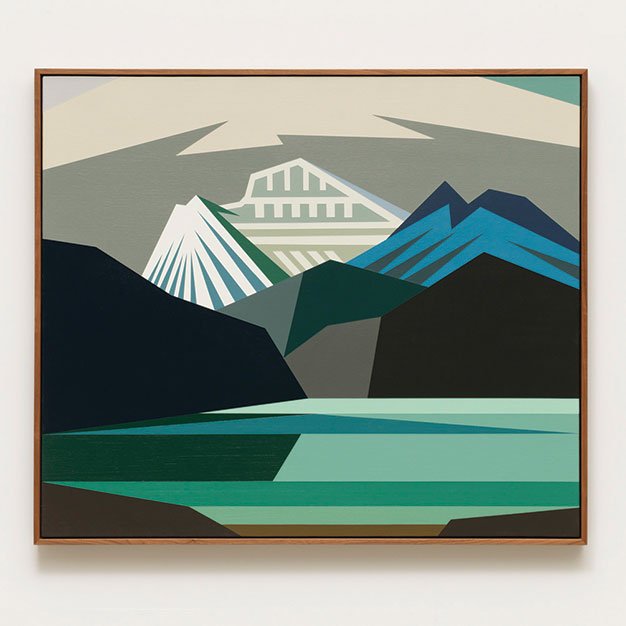

None of it is meant to be particularly moving, but the ideas are always pithily relevant and worth a wry chuckle. His copies of group of seven landscapes interrogate the relevance of their work in an increasingly digitized world. Coupland makes the joke that, in the digital age, since most people see works by the Group of Seven online, they experience them as a blur of pixels on a screen. Eventually, those iconic paintings will be remembered as blurry pixels of landscapes painted by some Canadian guys in the last century.

In another room, two utopian visions are pitted against each other. Lego sets reclaimed from his boyhood form a perfect 60s suburb, with houses repeated neatly ad infinitum in an ominously precise grid. A utopian fantasy skyline of the future stand on the other side of the room, with colourful blocks assembled freestyle into impossible towers. Our future may lie somewhere between the two, or neither may be applicable. Even so, he shows how fantasies of the ideal urban life are central to the way it is lived and constructed.

The high point is the sculptural assemblage Canada House, in which he attempts to fit all things quintessentially Canadian into a space the size of a one-story duplex. Raw plywood lines the walls, to which he affixes hubcap quilts and photographic still lifes of stacked plastic chairs, tires, lobsters and boxes of May West pastries. Modernist lounge chairs upholstered in lumberjack fabric occupy the centre. On plywood shelving on one end, Coupland meticulously arranges hundreds of tiny objects, from Saskatchewan licence plates, cans of Spam and hockey masks to miniature bison and a package of butcher paper labelled “WHALE MEAT.” Each is its own quiet in-joke specific to a Canadian region, giving a sense of the rural-ness and diversity of life up North.

In his tepid review of the show in the Toronto Star, Murray Whyte called Coupland on the carpet for not being a fiery sensualist like the equally diverse German painter and multimedia artist Sigmar Polke (who had a career-spanning retrospective at MoMA last year).

Fair enough, but isn’t Coupland’s entire ethos designed to show us how we are shaped by the most negligible of gestures? His exhibit is nothing more than the detritus of late capitalism: tchotchkes, toys, pencil crayons, souvenirs, advertising, signage and other throwaway media.

By curating and reorganizing these bits of disposable culture, he is showing how we are affected by the thousands of tiny intrusions that global markets insert into our lives with ever-increasing insistence and stealth. The future is increasingly insidious and anonymous, not so much defined by any authorial stamp as by marketing and mass production, accessed by solitary figures making tiny clicks on glowing digital screens.

Coupland is unable to resist the borderline obssessive comfort of re-arranging the near-infinite number of random things that contemporary life throws at us into some semblance of order, even as he realizes that the effort is futile.

It’s a strange and unfathomable world we’re edging into, and his 14 novels have said as much. Even so, he can’t help saying, in one of his deadpan posters at the museum’s entrance, “I miss my pre-internet brain.”