Two summers ago, there was in incident at our neighbourhood park involving my daughter, who was six at the time. This story requires a bit of context, so forgive the long set-up, dear reader. But it explains why I am thankful that David Chariandy, who brought us the complicated stories of suburban Scarborough through his novels Soucouyant and Brother, has written a non-fiction book called I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You: A Letter To My Daughter (McClelland & Stewart).

Like much of Toronto, we live in a racially diverse neighbourhood, just a little west of Yonge and Finch. Parents admonish their children at the nearby playground in Farsi, Korean, Tagalog, Russian and Hindi (that would be me!) among other languages. We were out on a rather hot day, loaded with water bottles and slathered in sunscreen. And just that morning we’d talked about different skin tones and the importance of sun protection for all.

It was so hot that the playground was empty, save for another young girl, whose mother was chatting with her in Spanish. My kids quickly started running around with her. A short while later, another mother and her two daughters arrived. After a few minutes, that mother moved to a shady area where her younger daughter was playing, while her older daughter stood near my children and the young Hispanic girl.

I had been half-listening to the children’s patter when suddenly I clued into the fact that my daughter and the young Hispanic girl were comparing skin colours. The girls had their arms out. My daughter pointed out the young Hispanic girl’s lighter skin tone. Then my daughter pointed to the older girl and said, “Her skin is darker because she is from Africa.”

I saw a look cross the older girl’s face. While I tried to think about how best to address the exchange, the older girl stalked off to her mother. I followed and did my best to explain what had happened. I was mortified. The mother was good-humoured about it all. In our short conversation, we established that I had grown up in New Delhi, and that her family had recently moved from Ghana. I tried to get the girls to play together but the situation had become awkward. Within another 10 minutes, the Ghanaian mother and her two daughters left the park.

As I watched them leave, I felt I had failed in that moment.

Later that day, and many times since, my husband and I have taken every opportunity to talk to our children about complicated ideas of identity. It’s not the easiest conversation to have. Yes, as a South Asian woman, I can talk about my experiences with inequity. But I also understand prejudices in my own family and social circles, ranging from a vague distrust of other racial minorities to definite cases of anti-Black racism there’s also the added complication of religious, ethnic and caste differences within India.

I have, of course, read works such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Dear Ijeawele, Or A Feminist Manifesto In Fifteen Suggestions, as well as Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between The World And Me. (James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time is on hold for me at Toronto Public Library, and I have been reacquainting myself with the works of Indian thinkers such as B.R. Ambedkar lately.)

Those books have helped me in my own attempts at discussion with my children. I added Adichie’s righteous calls to actions to my own mental checklist. Coates’s premise that constantly asking questions – especially when there are no easy answers – is a form of finding answers struck a chord, even as his visceral descriptions of growing up in Baltimore added to my understanding of his specific experience.

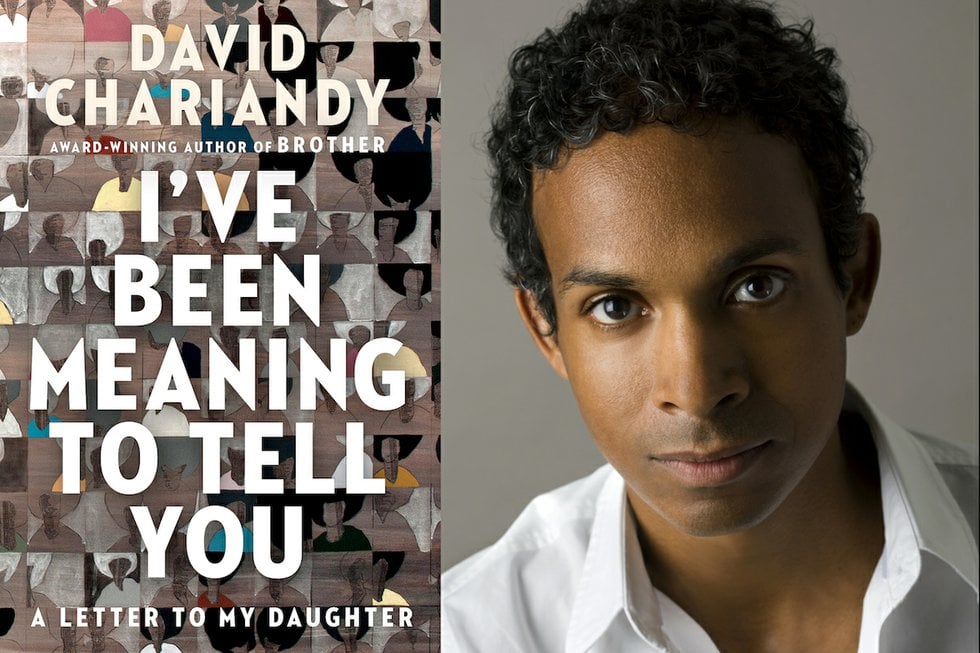

Which brings me to David Chariandy’s I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You, a book that adds to my evolving understanding of ways in which to carry forward these conversations, but in a Canadian context.

Chariandy’s latest work is also written like a letter – to his 13-year-old daughter. However, where Adichie and Coates put forward necessary and forceful arguments in the face of urgent and tangible instances of violence, I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You also adds layers of nuance.

Through it we understand Chariandy’s particular experience growing up as a son of Trinidadian immigrants (his mother is Black, his father South Asian), being married to a woman who tries “to live ethically as a white settler upon Indigenous land.” He’s raising a daughter at a time when she can both watch YouTube videos of IISuperwomanII and confront the news story of Alexandre Bissonnette shooting and killing six men at a Quebec City mosque.

There are no how-tos or hypotheticals in Chariandy’s slim book. Instead, there are stories, explaining how he navigates life in certain moments. It gives readers a powerful tool: the language to engage, even as our children roll their eyes at us in our attempts to speak to them using their forms of slang.

The other day my daughter saw an advance copy of I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You on top of my laptop. “What’s it about,” she asked. “Is it for me? I mean, kids like me? Because it says letter to my daughter.”

I told her we’ll be reading it together soon.

David Chariandy launches I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You: A Letter To My Daughter on June 6 at the Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema. See listing.

books@nowtoronto.com | @aparita