How do these transitory living spaces become second homes? I went on a mission to learn about their design, both theoretical and practical.

In fact, they don’t become homes – not really. They may use some home-like decor elements, but their goal is never to become permanent.

The Shangri-La and Beverley Hotels are designed as destinations, ultimate escapes where you can revel in luxury or voyeurism. Bridgepoint Hospital aims to get patients back out the door ASAP, while the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health is creating an urban village to help clients more easily reintegrate into the community.

Both the Toronto South Detention Centre and Roy McMurtry Youth Centre are designed to prevent incidents that could extend inmates’ stays or see them become repeat guests.

Turns out planning temporary spaces is a delicate balancing act, perhaps one reason why progress in this area seems so sluggish. Hotels are slow to differentiate themselves from one another, while public institutions struggle to leave the 20th century behind in order to become more effective and humane.

As a result, tracing these places’ design journeys is at once both inspirational and maddening. It’s clear that transient spaces play a tremendously important role in our society, and design is key to their success or failure.

Toronto South Detention Centre

160 Horner, Etobicoke

Going to prison in Canada isn’t a pretty proposition. Yes, detention centre design has come a long way from the dungeon-like Don Jail, but it still lags far behind the standard set by some European nations.

Norway’s state-of-the-art Halden Prison, for example, was dubbed “the world’s most humane prison” by Time Magazine. It features wall stencils by a famous street artist, a recording studio, jogging trails and a kitchen laboratory for inmates to take cooking courses, among other dorm-like amenities.

It has no metal bars, and inmates’ rooms resemble Ikea showrooms, complete with flat-screen TVs and en-suite showers. Guards are so integrated with prisoners that they play basketball together and share meals.

In Ontario prisons, “state-of-the-art” refers to residents’ ability to participate in religious services and the use of Body Orifice System Scanning (B.O.S.S.) chairs in place of manual cavity searches.

The Toronto South Detention Centre is the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services’ new $594 -million darling in Etobicoke. It’s a 234,000-square-metre expanse of concrete and plexiglass that will eventually house 1,650 inmates (assuming TSDC doesn’t run into overcrowding problems like the Don).

“We’re more oriented toward the American than the European philosophy,” says Alan Munn, senior partner emeritus at Zeidler Partnership Architects, who was part of the design team.

“European [institutions] tend to allow prisoners to have more personal stuff in their cells. But you only need to do that if someone is there for more than 18 days.”

At TSDC, a provincial detention centre, the longest sentence served is two years less a day. The average length of stay is 18 days.

There may be a big difference between a sentence that totals just over two weeks and one that spans two years, but there’s not much difference in the two very different types of inmates’ living facilities.

“Unfortunately, most of the units are designed to be very much the same. [The ministry] wanted that so staff get used to how the unit works,” explains Munn on the phone from his Toronto office.

The main impetus behind TSDC’s modern design is safety and security. Inmate movement, deemed risky, is kept to a minimum, with video-link technology for visits and open-concept cellblock units, each with a guard station, a day room with metal tables and chairs, TVs, a seating area of unmovable chairs and a yard. Residents essentially never have to leave their unit.

There’s a reason for that.

“Most house only 40 people so you won’t have massive numbers of inmates getting together and starting a riot,” says Munn.

Designers attempted to make the detention centre kinder than those it replaces, but considering those facilities’ human rights records, that’s not exactly a grand ambition.

“We made the spaces as humane as possible within the parameters we were given,” says Munn. “We tried to get as much natural light into the spaces as we could and to deal with acoustic issues so the space wasn’t as hard acoustically.”

Rather than numbering the day rooms and cells, the architectural team colour-coded the spaces in an effort to add some warmth. They also included facilities for aboriginal ceremonies and a multi-faith worship room that includes a footbath for Muslims to cleanse before prayers.

TSDC’s exterior is designed to blend in with the surrounding community. It’s also bigger than it looks from the main road.

“We wanted to make it look much more like a civic building. All the public spaces are welcoming, open and filled with light,” says Munn. “It’s important to create the right type of feeling for the community, not just for the inhabitants.”

Roy McMurtry Youth Centre

8500 McLaughlin, Brampton

Even when a prison’s design team has the best intentions, our government’s fear-first, think-later response to inmates can undermine everything. When it came to incarcerating Ontario’s youth, the Ministry of Youth and Child Services granted designers of the Roy McMurtry Youth Centre in Brampton a little more leeway, but was quick to backtrack on progress.

“The perception by staff, I think, is that these kids are a threat,” says Gerald Lambers, part of the team at Kleinfeldt Mychajlowycz Architects that worked on the centre. “They became very concerned about their [own] health and safety, to the detriment of the kids.”

McMurtry houses young offenders aged 12 to 18. The average length of stay is six weeks, but some kids spend two years or more there.

Lambers and his team were acutely aware of the dire conditions in existing youth detention centres.

“The instances of self-harm were just astonishing,” Lambers tells me in KMA’s quirky and cluttered Toronto office.

The theory was that brighter, more open and welcoming spaces would have an impact on the residents’ moods.

The facility consists of a series of cottages, each with two wings, 16 bedrooms, meeting and communal areas and an enclosed outdoor space with a basketball court. Each bedroom has natural light and ventilation, and the complex also has athletic fields, a school and areas for multi-faith worship.

“We tried to stay away from detention-grade hardware. It is, in fact, detention-grade hardware, but it looks like the hardware you see on your bedroom door,” says Lambers. Cell doors look like they’re made of wood.

McMurtry was built to meet LEED standards, so many of its materials aren’t typical of prisons.

“A lot of the materials are better-quality than those you’d see in a high school,” says Lambers.

Like Toronto South Detention Centre, McMurtry is a direct supervision facility.

“The vision was that guards would be on the floor interacting with the kids, talking to them. They’d know when a kid had a problem,” says Lambers.

“The reality is that when the facility opened, a lot of new staff were brought in, including experienced staff from the adult corrections system with a lot of old ways of thinking and doing things. Their immediate response was to harden the facility,” explains Lambers.

Many of the natural materials used to soften the prison’s look were removed. Windows for guards to peer through were suddenly installed in previously windowless washrooms, eliminating precious privacy for teens.

“It was kind of contrary to the original vision,” says Lambers. “We don’t have much involvement with the facility at this point.”

Bridgepoint hospital

14 St Matthews

We live in a 21st century world with 20th century hospitals. Our not so fondly nicknamed Hospital Row on University is arguably one of the city’s most depressing stretches.

Towering behemoths of drab brick and concrete dominate, while their interiors are worse for wear. Unforgiving fluorescent lights and shades of lifeless hospital green make these institutions places to avoid you don’t want to come here unless something is seriously wrong.

Infrastructure Ontario is trying to usher in a new generation of hospitals that don’t reek of anxiety, illness and the dreaded D-word. The new Bridgepoint hospital in Riverdale leads the effort with a fresh outlook on the ways good design can make a hospital, its patients and the community it serves better.

Bridgepoint provides rehabilitation and restorative care for patients who have complex medical conditions and who suffer from brain trauma or neurological issues.

“There’s a whole new frontier in health care. We need to take a different approach,” says Bridgepoint Health president and CEO Marian Walsh, a petite woman with electric energy that fills the room. “It’s not enough to just treat people and leave them to languish. How do we help people to live well with these conditions?”

In addition to caring for their physical well-being, Bridgepoint harnesses the power of design to produce positive psychological effects. Administrators are acutely aware of the strains hospital life can have on the psyche.

“There’s lots of research on the psychological and physical benefits of being connected to the landscape,” says Walsh. “We want people to benefit from the healing effects of nature, not to feel isolated by their health problems.”

As a result, every individual patient space has two windows – one horizontal and one vertical. “Everyone who comes here comes in an ambulance – they’re bedridden,” she says. “The horizontal windows enable patients to feel connected from the moment they arrive.”

The vertical window is a metaphor for the hospital’s goal, which is to help patients eventually stand and walk again.

Natural light plays a major role in the building, which is more or less encased in floor-to-ceiling glass so you can see through it from almost any angle. Views of the city help patients feel less secluded from the outside world.

Bridgepoint uses warm colours – no hospital green here – and wood finishes to make it feel more like home. Walsh boasts of features like flower gardens, a labyrinth and the future addition of 222 full-size trees, multi-use bike paths and a public park.

“Nothing here is accidental or ornamental. It all has a meaning: to call people to life.”

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health

1001 Queen St W

Across town at Queen and Ossington, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) is undergoing a massive redevelopment with similar design goals. Every building will be demolished and rebuilt by the time the project’s completed in 2021.

CAMH’s new vision is called “the urban village.” The aim is to use smart design to integrate the centre into the neighbourhood and reduce the stigma that surrounds mental illness.

The centre will welcome in the community by extending existing streets through the property. CAMH facilities and non-CAMH buildings will be integrated, and parks and pedestrian paths will be improved “so [the site] becomes like a normal city block,” explains Alice Liang, a principal at Montgomery Sisam Architects, the design team behind the redevelopment.

There are some limitations when creating spaces for patients with mental health issues, especially those in acute care. “For acute clients, the primary goal is their safety and the safety of staff,” says Liang, a no-nonsense woman with a short bob to match.

All design elements in the acute care facility must be anti-ligature, meaning there’s no way for patients to potentially hang themselves. Door handles, hinges, curtain rods and even hooks in bathroom stalls have to give way if anything more than the weight of a jacket is placed on them. Unlike in other health care facilities, sinks can’t be automatic because some patients will drink themselves sick.

“It’s about being aware of those considerations but not allowing the design to be hijacked by them,” says Liang. “It shouldn’t look like a prison.”

The design team also worked to conceal the cameras placed around CAMH to monitor patients. “Some clients suffering from paranoia are further agitated by the cameras,” says Liang. “Our goal is to design as calming an environment as possible.”

Building interiors now feature warmer colours and softer textures to look more like homes or dorms than like a harsh hospital setting. Strategic use of brighter shades also serves to help orient patients around floors and spaces that can easily start to all look the same.

“The surrounding environment has to be as normal as possible, not only to better re-engage them with the community when they leave, but also to remind them of where they came from,” says Liang.

Bedrooms have three different types of lighting that patients can control, none of them fluorescent. Communal areas provide a space for socializing and watching TV, while hallways feature reading nooks. Comfort and normalized living are key.

“All hospitals built in the 21st century are looking to hotels, because at the end of the day, the facility is serving customers,” says Liang. “We now often refer to hospital design as hospitality design.”

The Beverley Hotel

335 Queen West

A soft thumping emanates from the front window of an unmarked building. A DJ stands inside, his back to you, swaying with the beat while he spins for clusters of Queen West cool kids drinking craft beer and tucking into duck-fat kettle corn. Their warmth contrasts with the sheets of steel and hard, uneven concrete that line the room.

The window frames the space like a living Instagram photo, its subjects perfectly filtered by the low glow of bulbous overhead light fixtures.

You aren’t the only one watching. Inconspicuous reflective wall panels – so discreet you could easily miss them altogether – allow guests to steal glances at one another without so much as a turn of the head.

And in the guest rooms, the bathrooms are a peeping Tom’s wet dream.

Welcome to the Beverley Hotel, a place to be seen, subtly a setting tailor-made for a generation whose voyeuristic tendencies and desire for privacy are at constant odds.

The hotel’s restaurant and bar combine the clean lines of Scandinavian design with Queen West-inspired elements.

“It’s a cleaned-up version of Queen West. It’s street culture, it’s raw,” says Paolo Silverio, the hotel’s interior designer and an OCAD graduate.

“Everyone on Queen loves to wear dark colours, so it is very dark here. We have the cement floors, the steel,” he says, very much the part in a black leather jacket. There’s also a mural fashioned from a photograph of Armistice Day celebrations in Toronto.

As the night deepens, city dwellers move on from the Beverley and 905ers stumble in. The hotel caters to a very special subset: party-hard suburbanites who need a downtown place to crash.

Guest rooms are small and simply designed, not meant for much more than passing out in the most dignified manner possible.

“I call it a cleaner version of Ikea,” says Silverio.

The rooms’ quirkiest design feature are the bathrooms that provide all the privacy of a fishbowl. Some are fully encased in clear glass others have oversized windows that connect with the bedroom.

Either way, your bunkmate is afforded a full view of everything you do in there. Silverio figures the design will appeal to guests’ inner voyeur and that most people who share a room are likely pretty intimate already.

As it turns out, if you want to get to know a hotel’s personality, the bathroom is a good place to start. The room with the white throne speaks volumes about the guests designers envision staying there and the experience they’d like them to have.

Shangri-La Hotel Toronto

188 University

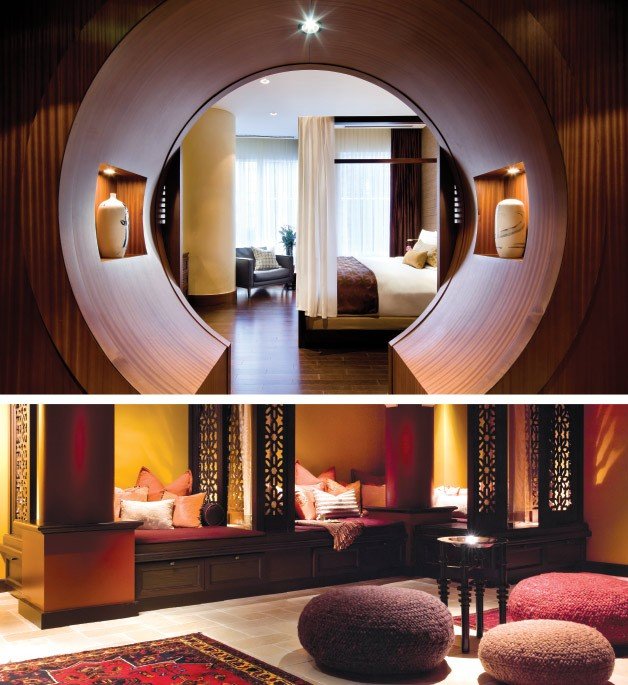

A few blocks from the Beverley, in a suite at the Shangri-La Hotel, grand double French doors open to a washroom swathed in black-veined white marble. You glide across heated floors to a distinctly Asian oak table, on top of which sits a dual vanity and mirrors embedded with a sleek LCD TV. L’Occitane bath products on the countertop whisper, “Try me!”

Choose between a separate glass-enclosed shower or a luxurious deep-soaking tub. Hell, take both for a spin. For those with deep pockets, an Italian crystal chandelier and a balcony the size of a bachelor pad are part of the mix.

The Shangri-La is all about extravagance. The hotel sticks to the Asian-inspired style for which the chain is known, using walls panelled with raw silk, richly coloured carpets and subtle calligraphy paintings by Chinese artist Wang Xu Yuan to feel authentically exotic without seeming like a caricature.

But the hotel isn’t just a travel destination. It’s important to the owners that it be a local hot spot. In addition to business travellers and ritzy socialites, the hotel targets the same cool kids as the Beverley.

Enter the strategic inclusions of Soho House and Momofuku restaurants on the property, and a lobby that’s become one of the city’s most popular places to grab a drink.

More than a mere lobby, it’s a community hub, a place where the hotel’s patrons connect and clink champagne flutes. It was also one of the most challenging spaces to design.

“It was really tough, because you want it to be grand but also feel intimate,” says Renata Li, a designer and architect at Westbank, the hotel’s development group. On the phone from its Vancouver headquarters, she tells me the trick is in “pulling the space away from the entrances, so that it can become its own intimate space.”

Li and a team from McFarlane Biggar Architects + Designers used a wood wall fashioned by Quebec woodworkers Beaubois and a sprawling double-sided fireplace to add warmth to the space. Residential-scale clusters of furniture and smaller objects like teapots make the space feel more like a home.

Overnight stays are just a small part of the equation here. Next up, the hotel aims to become a major musical venue – a rather unusual but exciting aspiration for a luxury hotel. While their competitors stick to the status quo that often seems more about money than taste, the Shangri-La, in the true spirit of hospitality, is expanding its welcome.