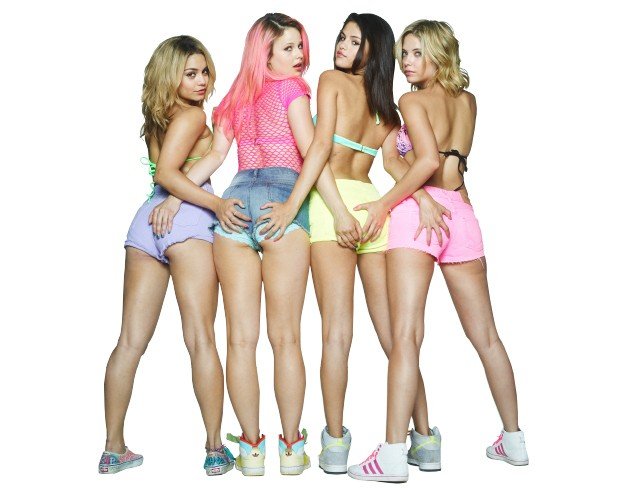

SPRING BREAKERS written and directed by Harmony Korine, with Ashley Benson, Rachel Korine, Heather Morris, Vanessa Hudgens, James Franco, Selena Gomez and Gucci Mane. A VVS Films release. 92 minutes. Opens Friday (March 29). For venues and times, see Movies. Rating: NNNN

Maybe every generation gets the spring break movie it deserves.

In 1960, four Midwestern college girls decamped to Fort Lauderdale to face the swinging 60s’ changing sexual mores in Where The Boys Are. In the 80s, feminist subtext receded as dweebs flooded Florida to retake the beach in horndog films like Revenge Of The Nerds II: Nerds In Paradise. By the early 2000s, the boozy beachfront bacchanal had been appropriated by bland corporate interests, resulting in Razzie-worthy flops like MTV’s The Real Cancun and ill-fated America Idol spinoff From Justin To Kelly.

Enter Spring Breakers, a movie no less tailored to its time. Scored by Skrillex and starring teen idols Selena Gomez, Vanessa Hudgens and Ashley Benson, it has all the ingredients of the typical sterile fun-in-the-sun romp. But as scripted and directed by Harmony Korine, it comes off as a necessary intervention in the whole degraded beach party cinema canon – even if its director swears he’s never seen a movie from this genre.

“I wasn’t even trying to make a spring break film,” says Korine from New York City. “It’s more of a backdrop for this other film – almost a beach noir or something.”

For sure, there’s not another spring break movie like Spring Breakers. For Korine – a director who elbowed into American filmmaking in 1995 as the twitchy teen writer of Larry Clark’s AIDS-panic indie Kids and then established himself as a pop-avant enfant terrible with directorial features of his own like 1997’s Gummo and 1999’s Julien Donkey-Boy – Spring Breakers feels at once like the culmination of all his previous work and like nothing he’s done before.

Like its maker, Spring Breakers is astoundingly original, every inch its own thing.

Korine earned his rep in late 90s as one of the New York art scene’s more volatile members. (For a while, rumours circulated that he was banned from Letterman after giving Meryl Streep a shove backstage.)

But Korine’s not cut from Upper West Side intelligentsia cloth. He grew up in Nashville. His father made short films for PBS profiling the local carnies and moonshiners. This kind of portraiture permeated Korine’s still remarkable directorial debut, Gummo – shot in Nashville but set in Xenia, Ohio, a small town ravaged by a tornado, where moon-faced adolescents kill time hunting feral cats. The New York Times called it the worst film of the year – the kind of publicity a young filmmaker can’t buy.

Nashville’s just a 10-ish-hour drive down I-75 to Florida’s beachside tourist towns. Korine remembers the annual spring break exodus as a tradition in the South.

“White kids would go to Daytona Beach and celebrate in ‘the redneck Riviera,'” he recalls. “Now it’s more integrated. It’s more culturally diverse. It’s also become more corporatized in a lot of ways.”

In its opening scene, Spring Breakers skewers that diversity and corporate sheen. In a series of slo-mo tracking shots, multicoloured bodies writhe to the wonky electro tempos, breasts and beads bouncing in the sun, a snakepit of beer-slicked sexuality. This is the spring break of MTV or those tacky late-night infomercials advertising tapes of sloshed coeds exposing themselves for a free baseball cap. (It’s an almost cosmic coincidence that Spring Breakers arrives just a few weeks after the pervy tycoons behind the Girls Gone Wild videos filed under Chapter 11.)

The dreamy, impressionistic imagery plays, as others have noted, like an art-house Girls Gone Wild. For Korine, the pseudo-pornographic panorama of spring break was “a cultural ground zero: a debauched, apocalyptic free-for-all on the beach.”

The movie originated as a series of images pooling in its maker’s mind, among them lithe young women in bikinis wielding guns, their faces masked by pink balaclavas.

“I started looking at the pictures, and they were all super-sexualized, hyper-violent, real gutter behaviour,” he says. “All around them, in the details, were these childlike pop cultural indicators: nail polish, flip-flops, Mountain Dew bottles, styrofoam cups, puke on the toilet. It was like a private language, and it spoke to me in a strange way.”

This interplay of images is vital to Korine’s cinema. The tornado that lays the scene for Gummo’s rural dystopia is a recurring metaphor for its director’s aesthetic: elements of heavy metal, hip-hop and celebrity culture, broken-down bits of art, pop and schlock all pulverized into what Korine describes in different breaths as “a cultural mashup,” “a cultural mutation,” a “liquid narrative” and “a pop poem.”

That last description, pop poem, best describes Spring Breakers.

For one thing, there’s the pronounced pop element. Korine’s 2007 “comeback,” Mister Lonely, dealt with the fuzzy concept of stardom in its depiction of celebrity impersonators living in a commune in the Scottish Highlands. Spring Breakers busts through the looking glass, casting young super-starlets as gun-toting, exuberantly sexualized party girls. Like a whirlwind whipping through the Disney Channel, Spring Breakers whisks its family-friendly celebrities out of their safe, sanitized pop context and deposits them in the uncharted territory of the art house.

“There was a compelling conceptual narrative at play,” Korine says. “The girls in the film are very connected to this pop mythology that’s very much connected to the world of the film. It’s also very exciting that a completely new audience will get to see this kind of film.”

Korine’s coed quartet (Gomez, Hudgens, Benson and the director’s wife, Rachel Korine) fall under the sway of a cornrowed white boy gangster named Alien, played with loathsome aplomb by James Franco – last seen riding a twister in his own Disney star vehicle. After bailing the girls out of the drunk tank, Alien begins schooling them in his lifestyle of cartoon depravity (“Look at all my shit!” he barks, spinning through a gaudy mansion decked out with assault rifles and nunchuks, Scarface DVD looped on the TV) and bona fide real violence.

Calling Spring Breakers a brain-dead gangster film isn’t so much a denunciation as a statement of fact. This is Scarface for a generation that grew up watching Scarface on repeat, glomming onto the sensations while shrugging off its ethical underpinnings.

What’s most shocking – and bold – about Korine’s film is that it celebrates this stupidity. Like Kids, which drew praise for depicting its adolescent troublemakers without condescension, Spring Breakers rejoices in the emptiness of the cultural landscapes it depicts.

While Korine maintains that Spring Breakers is “about a culture of surfaces,” there seems be plenty churning underneath. In staging the moment when its rowdy partiers cross the line from romanticizing a culture of violence to actively immersing themselves in it, the film seems to comment on what happens when our own ideas of pulpy pop mythology bleed into reality.

Korine sees spring break as an outlaw rite of passage.

“It’s this fleeting moment,” he says, “when kids go and destroy everything and lose their virginity and take as much drugs as possible. Then they get in their car, go back home and pretend it never happened. I don’t know if it’s uniquely American, but it’s thoroughly human.”

Given his prankster-provocateur persona, it’s hard to tell if Korine’s being sincere. But Spring Breakers may be “thoroughly human” even if it it’s in the most vile, base way, its road-trip rallying cry ringing like a primal howl for its lost generation: “Spring break foreeeeeeeeever.”

johns@nowtoronto.com | @johnsemley3000