Part 1.

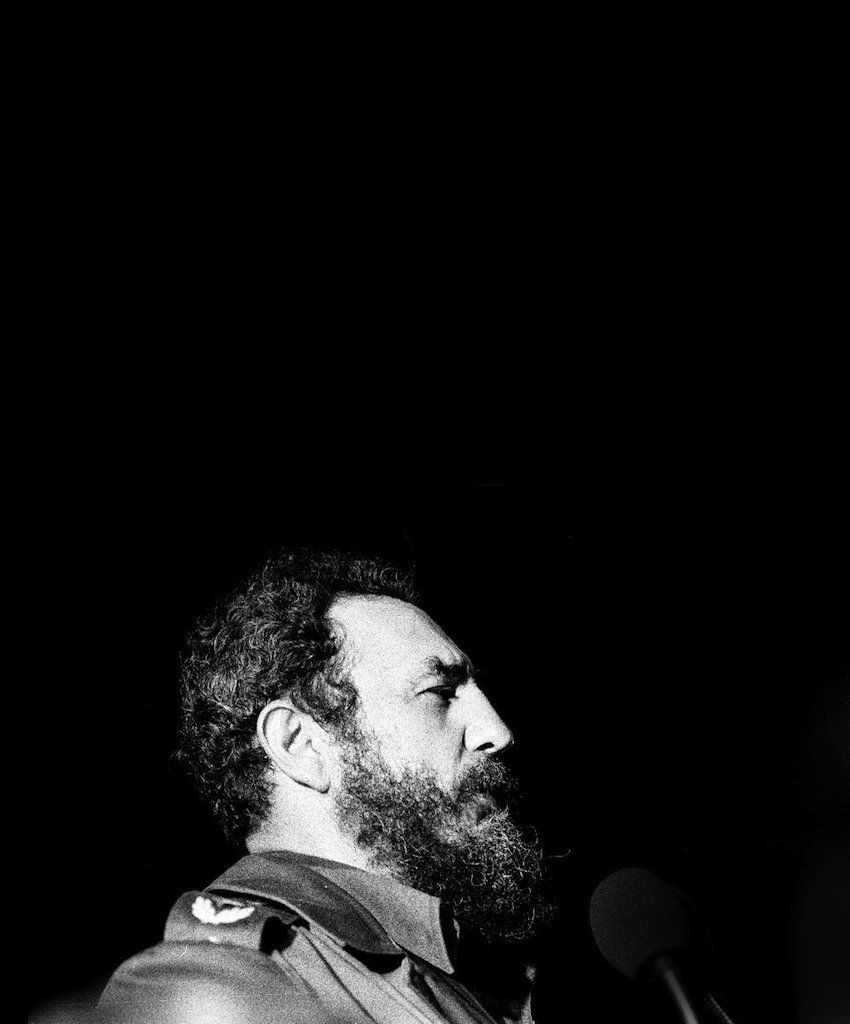

The life story of few political figures rivals that of Fidel Castro, the outsized Cuban revolutionary and former president who died last Friday, November 25, age 90. I can think of one in the modern era – Nelson Mandela. Indeed, Mandela’s first trip outside South Africa after his release from prison was to visit Castro in Cuba.

But most conservative commentators and politicians both here and stateside weren’t inclined to reach too far back into the Cuban leader’s life to offer an opinion on his death. Remembrances and eulogies focused on Castro the dictator and Castro the “murderous” tyrant, not Castro the internationalist. Initial reports of his death were met with news of dancing in the streets of Miami, where a large expatriate Cuban community lives.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s statement of “deep sorrow” for the “legendary revolutionary and orator” and “remarkable leader” was widely condemned, becoming fodder for listicles and such on the internet.

Conservative Party of Canada leadership candidate Kellie Leitch, she of “Canadian values” fame, quickly jumped at the opportunity to make political hay for her followers posting on her Facebook page a grainy black and white photograph of questionable origin purportedly showing Castro executing someone in cold blood.

“Justin Trudeau has embarrassed Canadians with his ludicrous statement,” Leitch pronounced on Twitter. “He needs to apologize and retract immediately.”

The same photo had been making the rounds on alt-right sites in the U.S.

But no matter. The mainstream was to busy following the blowback caused by Trudeau’s comments. It didn’t take long for birthers among the Twitter trolls to start claiming (again falsely) that Castro was Trudeau’s real father, complete with photo-shopped snaps to try and make the point. Conservative politicians half way around the world in Australia were weighing on that one.

Preposterous, of course, but in the brave new world of Trump where the leader of the free world is a former reality TV star and more people are reportedly reading fake news websites than the real stuff, even real news outlets are producing fake news. Call it a further descent into unreality.

Most critics like Leitch et al seem to have taken their knowledge of Cuban history from De Palma’s Scarface. (“Say hello to my little friend.”) They might be surprised to find out that Castro despised the so-called “elites” just as much as they do.

Castro was born into wealth, the son of a well-to-do sugar cane plantation owner who was well enough off to send Castro to the best education money could buy, first in boarding school and then under the guidance of Jesuits. Castro grew up a member of the Cuban bourgeoisie. He studied law at the University of Havana which is where he first learned about the injustices of the Spanish colonial system which left most of Cuba’s inhabitants impoverished and huge swaths of the country’s land in the hands of a small minority. It was also at the university where he became a student leader at a time when being a student leader and challenging the government of the day could get your beaten or killed.

He graduated law school in 1950, dedicating himself to working in some of Havana’s poorest neighbourhoods. It was during this time that Castro became involved in anti-racism work and decided to run for political office, nominated as a candidate for the House of Representatives. Fulgencio Batista had other ideas. A former president of Cuba, Batista would return to power in a military coup declaring himself president and cancelling elections. The U.S.-backed dictator gave up three-quarters of the country’s land to U.S. multinationals and control of drugs, gambling, and prostitution to the American Mafia. He tortured and killed his political opponents, an estimated 20,000 during his seven-year reign, many in public executions.

The rest, as they say, is history. After a number of failed political attempts to overthrow Batista, Castro became convinced that armed struggle was the only choice left. He led an attack on the Moncada Barracks in an attempt to obtain arms to lead his revolution. The attack failed and the rebels, Castro included, were rounded up and jailed. Many were executed. Castro, who made his famous History Will Absolve Me speech at his trial, was sentenced to 15 years for his part, but only served two years, released by Batista as a sign of goodwill over growing discontent with his rule, and especially his ties to wealthy U.S. corporate interests and the American Mafia. Castro would leave the country and launch his revolution from Mexico.

Contrary to popular belief, Castro wasn’t always a communist. In fact, Castro avoided an alliance with the country’s communists fearing it would drive liberals and political moderates away from his movement. His reluctance to embrace them was part of what led to his split with his lieutenant Che Guevara, who would leave Castro’s government and go onto is death leading another armed struggle in Bolivia.

The road to reforming a country ravaged by poverty proved a difficult one for Castro. the endeavor was made more impossible by the U.S. economic blockade imposed in 1961 which saw all but a handful of Western hemispheric countries join the U.S. in declaring what amounted to economic war on Cuba and driving the island nation into the arms of the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War.

There would be many mistakes made by Castro’s regime in the aftermath of the Cuban missile crisis that followed.

The socialist utopia Castro aspired to never materialized, at best it remains a work in progress, despite major strides in education, literacy and health care on the island.

But it was his five-decades battle with the U.S. that ultimately defined Castro’s legacy. There would be numerous attempts on Castro’s life by U.S intelligence. The resulting paranoia would ultimately see the regime defend itself by police and the military.

Castro would remain a key figure in the struggle for Latin American unity nonetheless. He gave refuge to leading figures in the Black Power movement in the U.S. and was among the first leaders to support the anti-Apartheid struggle in South Africa. To many Africans, Castro was a hero for his efforts against white minority rule.

Shortly after his death last week a meme started making the rounds on the Internet quoting Castro as saying he would not die until America is destroyed. It was probably just a fake. But America looks well on its way.

Part 2.

I should probably be the last person to defend Fidel Castro.

Back in 98, I was invited to travel as a journalist to cover the first Cuba Canada Meeting of Friendship and Solidarity in Havana. The trip was being organized by the Canadian-Cuban Friendship Association.

But officials with Cuba’s immigration department and the government-run International Press Centre seemed to have a problem with my participation.

And so less than 48 hours before I was scheduled to board Cubana Airlines flight 181, I got the call from Jose Garcia, Cuba’s consul general not to bother showing up at the airport because I would not be allowed on the plane. No official reason would be given, though it wasn’t hard to guess why Cuban officials were not eager to have me visit.

I had applied through normal channels. Made it known that I had planned to meet with average Cubans outside the planned tour with government and church officials.

But it appeared that my communications over the years with Cuban dissidents, among them Elizardo Sanchez, head of the Cuban Commission for Human Rights and National Reconciliation, had become a matter of concern to authorities. As had several articles I’d written about the jailing of human rights activists in Cuba, including the round up of members of the Concilio Cubano in 1996 – for which Amnesty International saw fit to bestow recognition at its annual human rights awards.

I like to kid about the episode. Tell people I’m the only (alleged) Commie to be banned from Cuba. Truth is, it was a disheartening experience. I had been on the island a year earlier, visiting as a tourist, and like many Canadians, had fallen in love with its mesmerizing beauty, history and people.

Looking back on it now I understand why Cuban authorities might not have wanted a journalist of my historical disposition about the politics there shitting all over their social experiment – even if I worked for a lefty magazine. Truth is I was probably just a little bit naive.

The government had passed new rules regulating foreign correspondents the previous June just ahead of the pope’s historic visit. They required foreign news agencies working on the island to hire local reporters through government offices. The country had built a political system that was the envy of the Latin American world it wouldn’t be a stretch to say, but almost 40 years after Castro’s Revolution, it continued to be a repressive and highly controlled society. The waves of repression seemed to follow a familiar pattern – not so bad when the economy was doing better, and ramped up during periods of economic upheaval.

“That’s the irony of Cuba,” the St. Petersburg Times’ longtime Latin American correspondent David Adams told me back then.

I had seen contradictions firsthand: the unemployed doctor I met playing maracas for a few cents on the beach, the vacant eyes of the young women offering sex for greenbacks in the night clubs, the men in military uniforms who appeared out of nowhere one day (apparently my friend and I had ventured too far from our resort) to check our “papers.” There was much wrong with Cuba, but most Cubans seemed to be able to smile in the face of the economic adversity.

A few years later, in 2002, I met with a leading figure of the Revolution. It was at the Royal York Hotel and on the occasion of the release of his book. Enrique Oltuski, was the Polish-born architectural engineer who emigrated to Cuba as a child with his Jewish shoemaker father, who would end up doing very well for himself in business.

Oltuski would later become vice president of the Cuban government’s Central Planning Board, where he worked under Guevara. His book traces his involvement as head of the urban underground student movement in Havana while Castro and Guevara were waging guerrilla war from their mountain bases in the Sierra Maestra. Like Castro and Guevara, Oltuski came from well-to-do family. I told him my story about being denied entry into the country. I’m not sure to this day if he was feigning amazement. He handed me his business card and told me not to hesitate to call if I ever did decide to visit the island again. He died in 2012.

And I have yet to go back, fearing (probably unjustly) that my name would appear on a list somewhere when I landed at the airport and that I would be turned back. Probably about time I made my peace.

enzom@nowtoronto.com | @nowtoronto