Last month, Norman Shewaybick trekked 17 days along more than 550 kilometres of treacherous ice roads from Thunder Bay to his Webequie home, hauling a full oxygen tank to highlight the crisis in health care afflicting northern Ontario’s First Nations.

“It’s not about being a hero,” he says. “It’s about saving lives, and how our health system isn’t doing its part for us.”

Shewaybick, a high school teacher and grandfather of six, was joined by his sons and two other supporters on “a healing journey home” inspired by the deathbed promise he’d made to his wife of 26 years, Laura. When she went into respiratory distress last October, the local nursing station couldn’t provide proper treatment because it had run out of oxygen. Her death at 51 might have been avoided if not for the substandard health care afforded indigenous people in remote communities.

“She was loved by so many, and many still grieve,” says Shewaybick. “I will miss her for the rest of my life. My grandkids come here and keep asking, ‘Where’s Grandma?’”

The oxygen tank Shewaybick brought home symbolizes the basic medical devices such as defibrillators, x-ray machines and other diagnostic equipment that are too often in disrepair or unavailable in First Nations communities. The seriousness of that problem was highlighted February 24 when leaders of the Nishnawbe Aski Nation and Sioux Lookout First Nations Health Authority declared a public health emergency to address “needless deaths and suffering caused by profoundly poor determinants of health” as well as “a level of health care that would be intolerable to the mainstream population of Ontario.”

The Sioux Lookout region is home to 33 First Nations communities with a total population of 30,000, some 80 per cent of them accessible only by air. The area has seen more than 600 documented suicides since 1986, a conservative estimate that does not include countless serious failed attempts. Prescription drug use and opioid addiction are rampant, and chronic diseases like diabetes contribute to the highest amputation rates in Ontario.

We have 10-year-old children committing suicide, and our people are living week to week with serious issues.

The litany of misery is a long one. Besides the severe obstacles to basic child health screening and poor access to treatment, the majority of health care staff are not fully trained, and jurisdictional spats over which level of government covers what service are a constant.

Shibogama Health Authority director Sol Mamakwa likens his eight years of work in northern communities to a war zone in which “the status quo has become acceptable and normalized. We have 10-year-old children committing suicide, and our people are living week to week with these serious issues.”

While he does not begrudge the welcome being given to Syrian refugees, Mamakwa notes, “We are a community about the same size as the number of Syrians who just came to Canada, and it would be great to receive the same sympathy and the same access to health care, to housing, to education.”

Instead, the communities he serves are caught in a “jurisdictional black hole” between the federal government and Queen’s Park, which instead of providing desperately needed services “play ping-pong over the health of our people.”

Mamakwa says the health care bureaucracies seem most interested in cost-cutting, and that despite the vulnerabilities faced by young people, northern communities can access a resident pediatrician only five days a month.

The plight of Sioux Lookout children was highlighted by Canadian Family Physician journal’s peer-reviewed study in October 2015 of eight cases of acute rheumatic fever (ARF), a preventable disease now rare elsewhere in Canada. The study documented the role played by inadequate and crowded housing as well as deficiencies in the health care system in these eight cases in one 18-month period. Two four-year-olds died, and the other six were left with rheumatic heart disease.

One of the authors of the report, physician Michael Kirlew, has worked in the North for nine years. Speaking to NOW just after putting a patient on a Medevac plane, he’s furious at the conditions he sees on a daily basis, noting that federally run nursing stations are “providing a standard of care that is far, far inferior to what other Canadians receive in almost every single respect.

“There are no checks and balances, and mechanisms for accountability are virtually non-existent. Care is being routinely denied to people under the non-insured benefits system, which really serves as a gatekeeper to care to decide which patient is or isn’t going to get what they need. It’s egregious. And we also have bacteria that take advantage of social determinants like lack of housing and clean water, so it’s a recipe for disaster.”

Kirlew has worked in Haiti, Guyana and other overseas locations, and “people’s jaws drop when they hear about these types of situations in Canada. So we need a fundamentally different way forward. The patient, the community and its values need to be at the centre, and the system we have right now fails on all three of those points.”

Some health care practitioners and community leaders are cautiously hopeful that recent political rhetoric about a respectful nation-to-nation relationship will translate into concrete action.

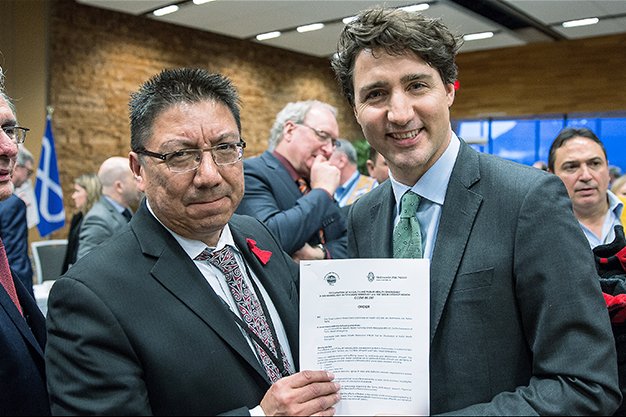

At last week’s First Ministers’ Meeting in Vancouver, Nishnawbe Aski Nation Grand Chief Alvin Fiddler personally handed a copy of the emergency declaration to Justin Trudeau, reminding the PM of the urgent need to address the crisis.

While Fiddler hopes to chat soon with Health Minister Jane Philpott, he’s already heard from Eric Hoskins, Ontario’s health minister, and received offers of support from a number of corporate players, as well as the Red Cross and the Heart and Stroke Foundation.

“They’re starting to realize the gravity of the situation,” he says, noting that symptoms of the crisis were further documented in a damning 2015 federal auditor general’s report.

The auditor general found that only one of the 45 nurses in the sample studied in northern Manitoba and Ontario had completed all five mandatory training courses. Some 30 separate deficiencies found in nursing stations by Health Canada itself had not been addressed.

“Right now, the funding we get is based on the Indian Health Policy from 1979,” says Fiddler.

Indigenous leaders insist that solving the crisis in northern Ontario and remote communities across the country goes beyond possible funding increases. What’s required is the modernization of outdated policies, community-based consultations and a holistic approach that, for example, considers colonial legacies, implements the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, respects indigenous cultures and tackles racism.

Those were the findings of a landmark 2015 Wellesley Institute report, First Peoples, Second Class Treatment, that concluded that “indigenous peoples experience the worst health outcomes of any population group in Canada, underscoring the urgency and importance of understanding and addressing racism as a determinant of indigenous health.”

That rings true for Mamakwa, who says, “Cultural safety is really important, and it doesn’t mean putting a piece of woodland art in your doctor’s office. People need to learn who we are, our history, and how institutions like education, health care and prison can sometimes be very racist. People also need to recognize that we are Ontarians, Canadians, First Nations people who are a part of this country. Right now we don’t just need health care. We need care.”

news@nowtoronto.com | @nowtoronto