It’s February 25 and I’m on my way to a railway juncture at Dundas and Jane where environmental collective Rising Tide Toronto has organized a direct action in support of the Wet’suwet’en in northern BC. It’s one of several actions in recent weeks in response to growing opposition to pipeline plans in Wet’suwet’en territory.

A young Indigenous man notices I’m having trouble and offers his hand to pull me up a hill. We stumble toward the distant crowd milling on the tracks.

When the OPP arrested Tyendinaga supporters who closed the rail line through their territory in support of the Wet’suwet’en last week, the media were kept at a distance.

When we arrive, arrests are already underway. They include a woman pastor, an Indigenous woman in a ribbon skirt, a young Black man, and two masked youth. Demonstrators unwilling to risk arrest have already retreated to the other side of the chain-link fence on either side of the track.

Deb O’Rourke

With only a few people on the tracks and dozens of police, it looks like this action might end soon. But an Indigenous woman, accompanied by a hand-drummer, holds off the police, and more people slip in out of nowhere to occupy the tracks.

What looked like a slam-dunk for police at 5:30 is impossible by six. The arrests stop. With bodies at risk and voices at full volume, a helicopter thrums overhead, the smell of sage rises, sassy chants intersperse with Indigenous songs and drums. “We’re unarmed. They have guns,” activists chant. “Who do you serve? Who do you protect?”

Indigenous singers follow with the beloved old AIM (American Indian Movement) song from the 1970s, a reminder that the struggle is not new. A speaker reminds the crowd: “We only have one job to do here, people, and that is to stand for the rights of our First Nations brothers and sisters. This is to remain peaceful. Let all of the hurt be on their hearts, not ours.”

I’m reminded of the principle of Satyagraha popularized by Gandhi, which is to peacefully stand up to the state with only your human vulnerability until the hearts of the public are changed and the state is forced to do the right thing.

Elder Pauline Shirt’s family is here to deliver a message for demonstrators – hold the tracks. Shirt’s family and other Indigenous drummers, singers and speakers, will be the calming, teaching voice throughout the night.

When feistiness and humour degenerate into taunting and insult, their voices rise above the crowd. “There are Indigenous people on the tracks doing ceremony, asking the Creator to bring our hearts and our minds together.”

Blankets are passed over the fence, along with pizza, samosas, donuts, water and coffee for those on the track. Someone from Tyendinaga calls over the fence to thank demonstrators. “Stay close and keep each other safe.”

Deb O’Rourke

As darkness falls, the rhythmic pounding of boots grabs everyone’s attention. Knees pumping, arms swinging, a large phalanx of police thunders along the tracks out of the dusk. The folks on the tracks link arms and hunker down, looking in their shawls and blankets like a pile of urchins from Oliver Twist. In that moment, I love every one of them.

When the officers break formation and run, I think we are in for a riot. But they don’t go for the people on the tracks. Instead, the make a line for supporters standing on the side of the track. Dozens scramble over the fence.

I find myself with my back to the chain-link, eyeing a line of officers. The people on the other side are angry. Anyone who went through the police excesses of the G20 would be. Some of demonstrators respond by challenging the police. Some are funny, some insulting, some philosophical. A woman calls out. “What will you say to future generations when they come and ask where were you when this was going on? That you were on the opposing team?”

“Serve and protect the planet!” some in the crowd suggest.

When things get tense, Idle No More’s Crystal Sinclair gets on a megaphone and leads the crowd in the Water Song, dedicated to the late water walker Josephine Mandamin.

“When I was in Wet’suwet’en territory,” says Sinclair, “I drank the purest water in my life. That’s what we’re fighting for. That is why we take strong opposition to pipelines and resource extraction. And that’s why we are all here today. So thank you for showing your love.”

Someone shouts that “police drink water too.” As I snap and record, a friend on the other side of the fence asks me if I’m OK. A nearby police officer assures me that whenever I’m ready to leave, he’ll make sure I get out safely. This officer is doing his job, so I can do mine.

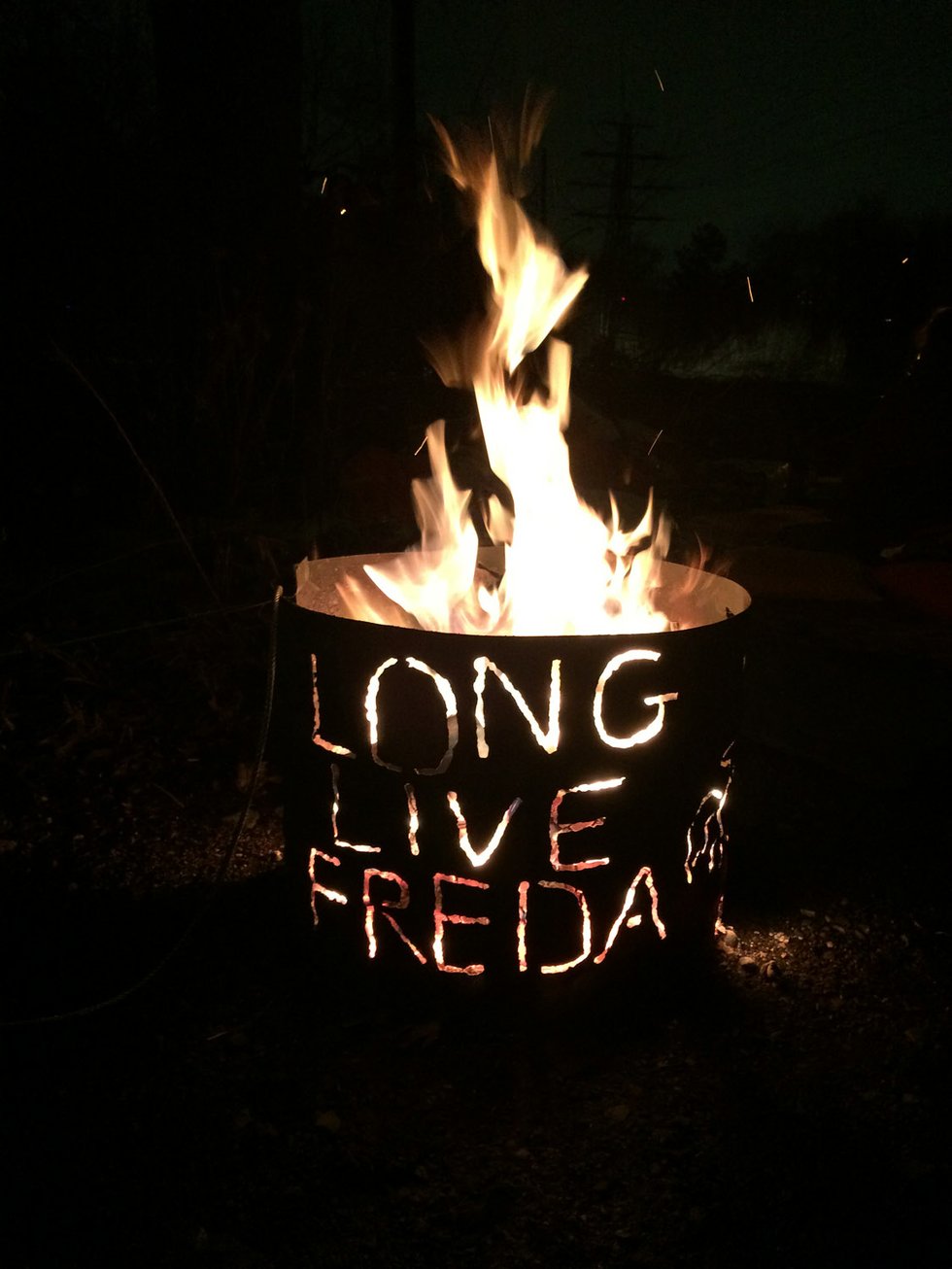

Free to explore again, I see that there more people, nearly 60, are now on the tracks. A fire-truck turns on its floodlight, illuminating the scene. Studying their all-too-human faces, I wonder how police feel about being ordered to be here.

In 2015, when Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission released its report, Senator Murray Sinclair offered that “We owe it to each other to build a Canada based on our shared future, a future of healing and trust.” He would later warn that if Canada did not follow up sincerely, it would face a generation that had no reason to trust the government, and no patience.

When the Liberal government was elected, it promised to work with Indigenous people on a “nation to nation” basis. Yet, the government seems to have ignored the warning of the 1997 Delgamuukw decision that it needed to work out relationships and title with the Wet’suwet’en and the Gitksan. That’s why we are all here now.

“When justice fails, block the rails!” the demonstrators shout. Toronto police peacefully handle hundreds of often rowdy protestors. It’s still not pretty and none of us really want to be here, but we are all able to fulfill our roles.

When I leave the crowd they are calmly chanting. “We are peaceful. We are unarmed. We are in solidarity with Wet’suwet’en.” In the early morning hours, police will remove the remaining protestors.

That’s their job, to safely do their part of a difficult but vital public ritual that we all have to endure when caught in the mess between conflicting interests over water, land rights and democracy.

Deb O’Rourke

@nowtoronto