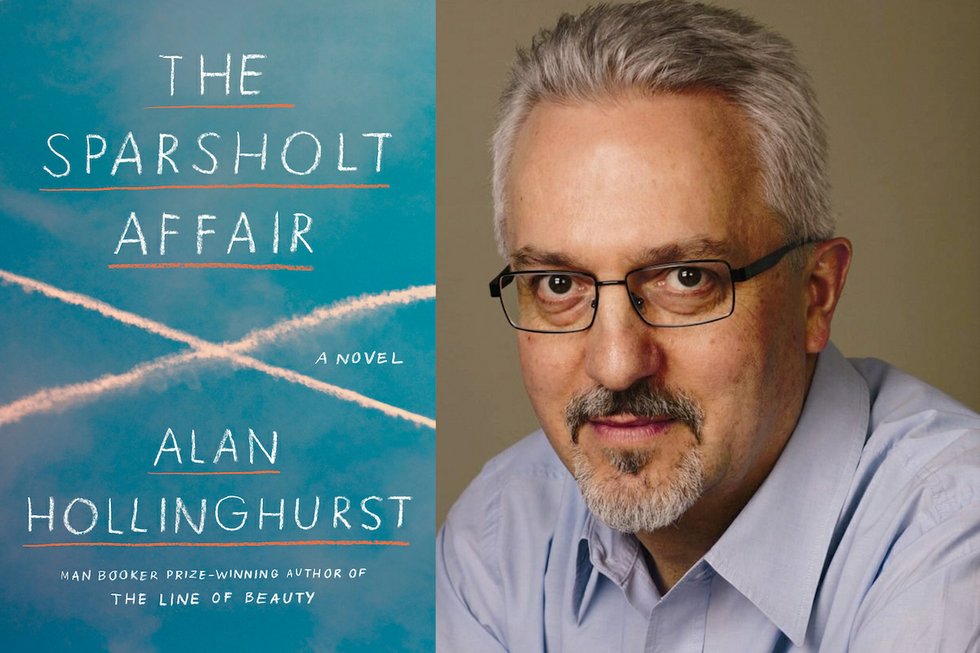

THE SPARSHOLT AFFAIR by Alan Hollinghurst (Knopf), 432 pages. $34 hardcover. Rating: NNNN

As I listen to UK novelist Alan Hollinghurst speak, the sound of David Bowie singing “Ch-ch-changes” fills my head.

Things are dramatically different since the Booker Prize-winning author (2004’s The Line Of Beauty), credited with mainstreaming gay fiction in Britain, released his first novel in 1988. For starters, there were almost no queer novels, let alone a gay canon.

“When I started writing my first book in 1984, I realized no one had [been writing this explicitly in the UK] before,” says the 63-year-old, clad in jeans and a plaid shirt and speaking the Queen’s English in a quiet voice. “Now, it’s to the point where I feel like the gay novel – which I was a part of in the 80s and 90s – has kind of dissolved. It’s not even a category any more.”

And whereas he used to revel in describing his characters’ sexual adventures in delicious detail, he’s now more interested in maintaining some mystery concerning erotic encounters. His latest book, The Sparsholt Affair, could be described as an ode to what’s unsaid and unseen, exquisitely ironic, given that he’s famous for having shed a bright light on the hidden lives of British gay men.

In the new novel, a post-WWII sex scandal has transformed the lives of RAF fighter David Sparsholt and his family. Hollinghurst is never explicit about what actually happened. We know the incident has to do with Sparsholt, a Tory MP and some male prostitutes and that’s about it.

In the first section, we meet Sparsholt in the 40s at Oxford, where he is the object of a group of closeted gay men’s intense erotic interest. One of them, Evert, succeeds in seducing him. The build-up is significant, the payoff, not so much, this from a writer who devotes pages of detail about foreplay in his debut, The Swimming Pool Library.

“The bedroom details interest me less and less – maybe it’s my own flagging libido,” Hollinghurst says with a self-deprecating smile. “I started writing openly about what men got up to together and it was great fun to do but I didn’t think it necessary to repeat it. And a conventional closing of the bedroom door is instrumental in creating a sense of mystery about behaviour, inviting the reader to speculate.”

The aging process has also messed somewhat with his writing process.

“I don’t get swept away by it in the way I did with my second novel, when at the end of the day you had a describable sense of satisfaction that you’d done something you didn’t know you were going to do. Of course, I have lovely days when I get carried away. But not as often. I think it’s a part of getting older.”

Ultimately the new book is the story of David’s son Johnny, who himself is gay and experiences the vast changes in the gay world, from the bar scene after 1967, when homosexuality was decriminalized, to the contemporary days of Grindr and online porn.

“As far as the scandal goes, I was less concerned about what happened then the depressing aftermath. People do a double take when they hear Johnny’s name. It complicates his sense of self now that he can do what his father did in secrecy.”

Then again, some things have not changed at all. Hollinghurst’s descriptive powers haven’t diminished in the slightest. His passion for visual art continues to infuse his work. Here it manifests in elaborate descriptions of architecture and other visual arts. And pursuing his fascination with portraiture, he’s made Johnny a painter of portraits.

“I’ve always been attracted to the very subtle things that a really great portrait can tell you about a sitter, and its survival in the world of the selfie is kind of extraordinary.”

In the new book, he revisits more intensely how young men are attracted to much older men and how intergenerational relationships have become a part of the gay male scene.

“People have sometimes said to me how different this would read in a heterosexual context and how creepy it would be,” he allows “but it’s always been a part of gay male life, the older man a mentor to a younger one and the young one who brings an older man back to life. And there’s the passing on of the wisdom and the lore. It happens a lot in the gay male world without it being the subject of squeamishness or censure.”

Also still going strong is his tendency to write in sections set at different points in time and which tend to end abruptly. The first section introduces us to Johnny’s maybe-gay father at Oxford, but then situates Johnny at different points in his own life.

“I always hope readers are engaged, even seduced by the book – that it takes people in directions they are not expecting it to go. I like writing in this disjointed way. What starts out to be the story of one person turns out to be the story of someone else. I always like it when people say they didn’t want the section to end.

“But readers respond warmly to that invitation.”

“You mean the invitation to think?” I ask.

“Yes, exactly.”

susanc@nowtoronto.com | @susangcole