“I feel like I’m swimming through mud here,” Steve Munro says over the phone as we near the one-hour mark of plowing through transit reports in search of answers to what should be basic questions.

Even semi-coherent transit plans are necessarily contingent on a dizzying number of variables, and Munro – the city’s pre-eminent citizen expert on the subject – is superhuman in his ability to recall and tie together such details.

But late in the evening before March 9, when city council’s executive committee would meet to consider several interrelated plans (including Mayor John Tory’s signature SmartTrack) even Munro seems more than a little stumped.

About the only thing that’s certain, as one report casually mentions, is that “all train services occur in space and time.”

So how often would SmartTrack trains come?

SmartTrack has always been a nebulous concept at best, something built on top of GO Transit’s Regional Express Rail (RER) plan that the province, through Metrolinx, was executing anyway. GO is already in the process of converting much of its network from a commuter rail service into an all-day, two-way transit system SmartTrack would piggyback on this by adding new stations in Toronto.

But for a long time it remained stunningly unclear whether SmartTrack would actually be its own service with its own set of trains running on the same tracks as the RER.

All we knew was that SmartTrack and RER were each promising trains every 15 minutes – a challenge, since running two 15-minute services on the same corridor would require new tracks to keep them from crashing into each other. Those tracks would be expensive to build, if there were space for them at all.

Only recently did staff from the city and Metrolinx acknowledge this.

In a February report examining how to “integrate” RER and SmartTrack, they looked at several scenarios for coexistence [pdf]. They concluded that whether the trains run as parallel services on separate tracks or as express and local services sharing much of the same track, the cost of new infrastructure would be prohibitive. Instead, both Metrolinx and city staff suggested, SmartTrack should be limited to the service already planned for RER, albeit with four to eight extra stops plopped in along the way.

In other words, SmartTrack would be the city and federal government kicking in money to build new stations that wouldn’t otherwise exist on the province’s RER lines. It would have neither its own trains nor its own schedule. The fares would be consistent with whatever Metrolinx decides to charge to ride the RER.

The original proposal for SmartTrack also included a new heavy-rail spur out to the airport, but that was a terrible idea for all sorts of reasons and will now be a westward extension of the Eglinton LRT instead.

SmartTrack, Metrolinx’s report states, will be held to “funded and committed GO RER frequencies in the peak and off-peak: 5- to 10-minute peak service [and] 15-minute off-peak service.”

The question that puzzled Munro and me on the phone that night: since when is RER supposed to be that frequent?

In report after report in 2014 and 2015, Metrolinx described RER as offering “15 minute two-way electrified service within the [greater Toronto and Hamilton area] urban area” [pdf] and “15-minute frequencies in core areas” [pdf]. The last three provincial budgets referred to RER as being “as frequent as 15 minutes,” having “about 15-minute frequencies” and having “15-minutes frequencies,” respectively.

But in this February report, the RER’s peak frequency was suddenly three times that, at up to five minutes – coincidental with a recent ridership study that found five-minute frequencies to be a necessary condition for making SmartTrack attractive [pdf].

What Munro eventually figured out was that these better-than-15-minute frequencies represent GO’s calculation of the total number of trains passing through a corridor in the peak direction in the peak period. That is, in the corridors relevant to SmartTrack, 15-minute all-day service on the busiest part of a line will be supplemented by a handful of additional trains heading from the outskirts of the GTA toward Union in the morning rush and in the opposite direction in the afternoon.

So if there are four 15-minute trains on the Stouffville corridor running from Union Station to Markham’s Unionville station, plus three 20-minute trains from Union all the way out to Lincolnville in the afternoon rush, that’s a total of seven trains an hour, or an average of one every 8.6 minutes.

Metrolinx

The agency confirms their thinking in a statement to NOW: “As part of the RER program, on many corridors peak service has always been planned for better-than-15-minute frequencies. We already offer better-than-15-minute frequencies through a combination of local and express services during peak hours on the Lakeshore East, West and Milton corridors and will continue to grow to meet demand and RER service levels.”

So if all those trains to and from Lincolnville make all local stops, and you’re travelling in the correct direction during the correct time window, then people at a new SmartTrack station might be able to take advantage of frequencies better than 15 minutes.

But even that would fall short of the five minutes that’s apparently required for substantial ridership.

Can all this stuff even fit into Union Station?

Every workable transit plan consists of a staggering assortment of factors that have to be brought into near-perfect alignment.

“Changing from an up-to-15-minute service to 15-or-better has immense implications for the scale of fleet size, yard requirements, signalling, Union Station operations, blah blah blah blah blah,” Munro says, “which would accelerate the point at which Union Station fills up to an earlier date than currently foreseen.”

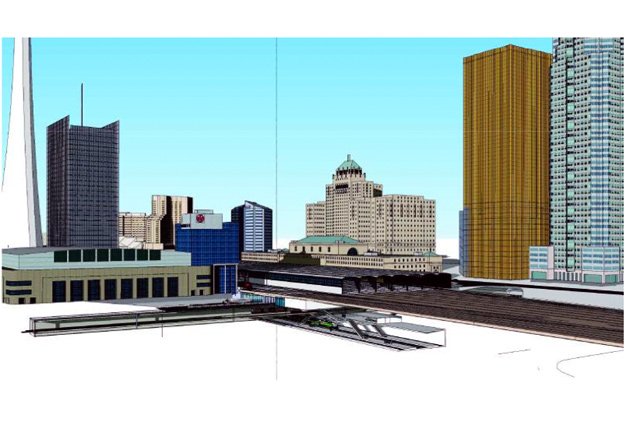

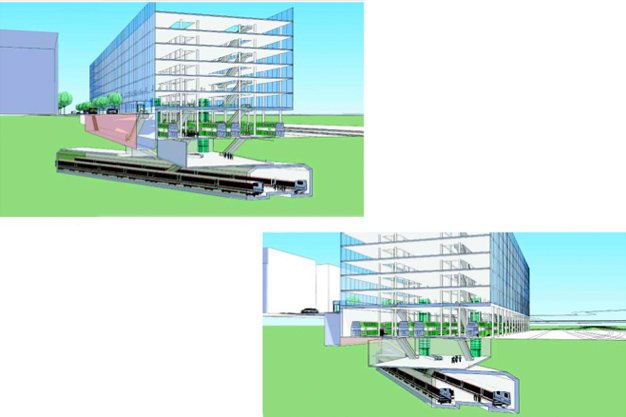

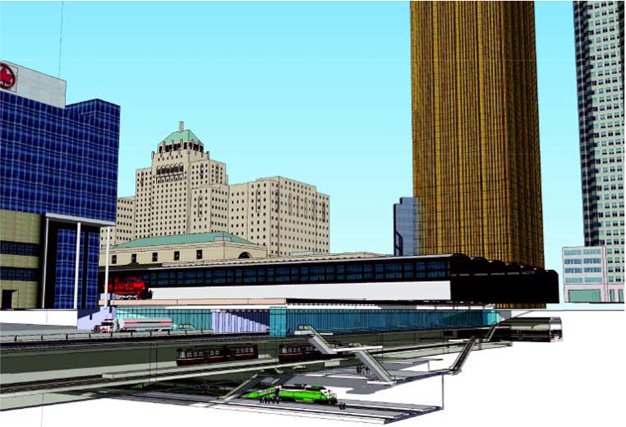

That’s because Union is going to run out of space in about 10 years’ time. There are related conundrums concerning the movement of passengers through the station, but here we’re just talking about the trains and the fact that there isn’t enough room to keep building tracks – particularly just west of Union where the rails are squeezed in next to the Rogers Centre.

Back in 2011, Metrolinx commissioned AECOM to study the capacity of the Union Station rail corridor and how it could be maximized. They came up with a host of medium-term solutions to make more efficient use of existing infrastructure, and those are now being implemented.

For the longer term, however, AECOM found that a whole second station will need to be constructed. One option they proposed was a new underground station a little east of Union that would handle trains from the Lakeshore East and West lines. That would cost at least $1.3 billion.

A second possibility was a new “satellite” station at the Bathurst North Yard that runs between Bathurst and Spadina just south of the current Globe and Mail offices on Front. The Barrie and Georgetown lines would terminate there instead of continuing to Union. But while this would be an order of magnitude cheaper than the underground option, the concept was premised on the notion that the TTC’s Downtown Relief Line (DRL) would connect that location to the core.

At last week’s executive committee meeting, however, councillors endorsed the DRL route now preferred by city staff, which wouldn’t see that subway make it any farther west than Nathan Phillips Square.

“We’re confident that we have the capacity over the 10-year horizon to meet the needs for GO Transit and RER and for Union Pearson Express,” Metrolinx CEO Bruce McCuaig told reporters at a February 23 board meeting. “We are looking at the longer term because we know that our vision right now is going out 10 years. But we know that if we think of 15, 20, 25 years, we do need to think about how we rely on a single facility of the nature that Union Station is.”

But given that it would probably take five to 10 years to build a new station, shouldn’t they be starting pretty soon?

McCuaig said they’re “doing initial planning work” on the strategy for Union and haven’t made any decisions yet, but it’s “one of those very active projects” that they’re looking at.

In an email, Munro imagines the nightmare scenario of SmartTrack service being too frequent to be handled by Union but at the same time too infrequent to divert riders from the Yonge subway.

“The Relief Line becomes more important much sooner,” he writes.

But as usual, that key piece of Toronto’s transit future, and the one experts agree is the single most crucial, is the only element that remains 100 per cent unfunded.

jonathang@nowtoronto.com | @goldsbie