Weird, but I get bummed when I see people gleefully setting up Halloween graveyards peppered with plastic skulls on their front lawn.

[rssbreak]

Like, it’s morbid. And wildly incongruous given our cultural tendency to regard death as something to be avoided by taking antioxidants.

And actually, I don’t like being frightened either. This wasn’t true when I was a teen and watched the Nightmare On Elm Street movies obsessively, which probably says more about me than I care to think about. But now I’m allergic to scariness.

Death and fear. Halloween is the day we honour them both. How far can it go in soothing our deep-seated angst?

“Modern Western culture doesn’t usually help people deal with loss in a healthy and effective manner. There’s no public and socially channelled grieving process. It’s considered gauche or declasse to actively grieve. Even funeral parlours have a separate room where you can break down. For Wiccans, [Samhain] is a time to say goodbye in a ritual setting to loved ones we may have lost over the course of the year and to honour others we have lost in past years as well as our spiritual ancestors. It’s a time and place to consciously take the time to close a chapter in your life and resolve issues you weren’t able to resolve when these people were alive. People get a lot of peace out of it.”

NICOLE COOPER, high priestess, Wiccan Church of Canada, Toronto

“Many societies regard the dead, as still part of the community. Halloween has been celebrated in places linked to Christian Europe it is still strong in Mexico. In many parts of Africa and in China, the dead became ancestors who were worshipped. If anything is unusual, it is our own practice of separating ourselves from the dead and dying. Among the Wari’, a forest group in South America, it was customary to cook and eat one’s dead relatives and was regarded as an insult to leave them in the cold ground. The Wari’ don’t do this any more but told an anthropologist they feel bad that they’re no longer allowed to give their ancestors proper treatment. One reason we remove our death rituals from a central place in society is that it’s rare for people to die before they’ve withdrawn from the mainstream of life, so there’s less of a threat to the core social fabric the ritual must protect.”

HARRIET LYONS, professor of anthropology, University of Waterloo

“Several things contribute to the enjoyment of scary movies, but none of these mean people enjoy the actual experience of fear. There’s an arousal dynamic in watching these films: an adrenaline surge, raised heart rate, systolic blood pressure and muscle tension. There is an enjoyment of the physiological sensation of arousal. When the movie ends, typically on a positive note, it causes an experience of relief and the arousal transfers over to the positive feeling, making it more intense. People leave these films feeling great. Males in particular experience what we call gratification from mastery.’ You sit through these films and say, I endured the gruesome images and made it through.'”

GLENN SPARKS, professor of communication, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana

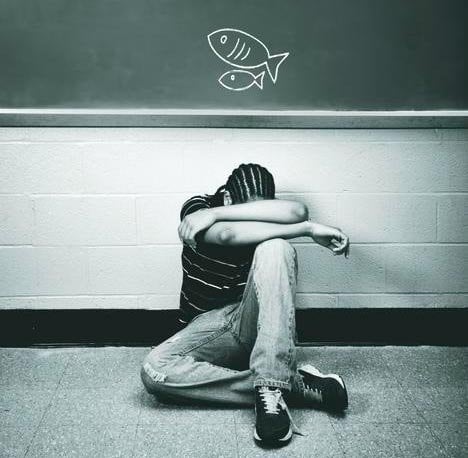

“Halloween is a safe environment in which to be provoked, and on another level it offers a sense of invincibility and mastery over death. It speaks to the simple reality that all of us, on a day-to-day basis, live with the understanding that life can end at any moment. I work a lot with veterans with PTSD, and one of the problems is that they truly have faced the probability of their own death and are unable to shake that anxiety and fearfulness. Symptoms persist, becoming debilitating.”

DAVID RUDD, professor of psychology, Texas Tech, Lubbock, Texas

“This is entirely speculative, but it seems that for children Halloween introduces a separation between our everyday experiences and a scary other world that, if you insert a bit of humour into it, becomes less traumatic or frightening. This can enhance creativity and spur the imagination. It might be a fairly innocuous way to introduce a child to questions at the heart of our mortality.”

JESSE BERING, director, Institute of Cognition and Culture, Queen’s University, Belfast