On a wintry evening in mid-December, a handful of people gathered in north Etobicoke’s Thistletown Community Centre to decide on the future of Toronto city council.

It was the sixth public meeting of the Toronto Ward Boundary Review, and organizers admitted that the sparse turnout — a dozen people divided evenly between members of the public and paid staff on the project team, plus a councillor — had been typical. The crucial and historic initiative to redraw Toronto’s wards and potentially increase (or even decrease) the number of councillors had yet to creep beyond the realm of the municipal wonks to whom such an exercise was catnip.

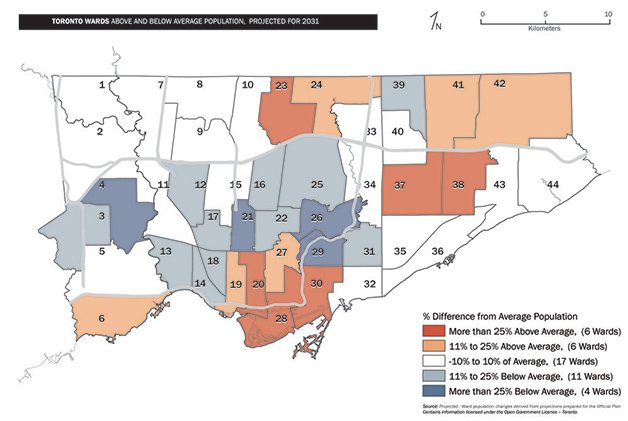

Toronto’s wards are out of whack. As it stands, the most populous district (Ward 23 Willowdale) has about twice as many residents as the least populous (Ward 18 Davenport and Ward 29 Toronto-Danforth). The disparities will continue to grow. The city’s population is projected to swell by about 20% over the next 16 years, and if the current boundaries were kept in place, the most heavily populated ward would have nearly three times the people of the least.

(Meetings in the Toronto and East York district kick off tonight, before heading up to North York next week. You can also fill out the survey online.)

Given that the current borders are effectively based on population numbers from 1991, this is not terribly surprising.

When the six municipalities of the former Metro Toronto were forcibly amalgamated by the provincial government in 1998, the new megacity kept the 28 wards of the old Metro council but stuck two councillors in each, making 56 in all. That year, the new city undertook a major review to forge new single-member wards that made greater sense, and council adopted a proposal to switch to a 57-ward system as of the 2000 election [pdf].

But over the course of two weeks in December 1999, Mike Harris’s Progressive Conservative government abruptly introduced and rammed through the Fewer Municipal Politicians Act. The new law micromanaged Toronto city council, mandating 44 single-member wards whose boundaries required approval from the Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing. The government further made it known that the wards should be based on the existing provincial ridings, which had themselves been brought in line with their federal counterparts drawn from 1991 census data.

Council assembled a three-councillor committee to hastily bisect the 22 ridings into the 44 wards we have today.

The city’s current project, branded Draw The Lines, is therefore the first proper effort to rationally delineate wards for Toronto (not counting the earlier attempt scuttled by Harris).

In Thistletown’s multi-purpose room, the floor adorned with hopscotch lines, the consultation focuses on the city’s western quadrant and what might be done to keep its wards at a roughly even population through the next four elections.

Consultant Beate Bowron goes through the Etobicoke York district one ward at a time. “Are there any issues regarding the boundaries of Ward 1?” she asks, adding, “And if there aren’t any, that’s okay.”

Sitting at the back, the ward’s councillor, Vincent Crisanti, suddenly tunes in and asks her to repeat the question. She does, and he replies with self-conscious curtness: “No. Ward 1 is good. Thank you.”

He has a point. Ringed by the Humber River on the south and east and by the city limits on the north and west, there’s not much that could be done. Although voter parity is the foremost consideration in drawing electoral boundaries, a 1991 Supreme Court decision stated that factors such as — but not limited to — “geography, community history, community interests, and minority representation” may also need to be taken into account. That is, in Canada the concept of “effective representation” outweighs the importance of absolute parity, such that it’s okay (and perhaps even desirable) to group people within a single district just because they share the same side of a river.

“Every time you draw a boundary, as you’re researching, you have to say, ‘Which communities have been split? Can you do that?’” explains Gary Davidson, another consultant leading the project.

Bowron says they won’t make the “same mistakes” as the recent federal redistribution whose new boundaries cut through neighbourhoods like St. Lawrence and Chinatown.

Part of it is about keeping neighbourhoods and other coherent cultural groups intact. But part of it is also about councillors’ capacity to represent their constituents, a rather more subjective concept.

Because the courts have said that effective representation involves making sure politicians are able fulfill their “ombudsman” function (i.e., solving issues for constituents), a councillor’s anticipated workload is another factor being considered by the project team. A ward with an influx of development applications could be allowed to have fewer residents, for example, not just because of coming growth but because the councillor’s time would be sucked up handling those projects.

And this leads in to what will surely be the most contentious element of any eventual proposal: the number of wards, and consequently the number of councillors, that it will take to effectively represent the residents of a growing city.

Toronto Ward Boundary Review

Ward population projections.

The average ward population was estimated to be just under 61,000 last year, going up to almost 74,000 by 2031. Consultation participants and those taking the web survey are asked what they think the population of a ward should be in order for a councillor to effectively represent it, as well as how many wards are necessary.

Out of an abundance of caution, however, council didn’t include any directions to that effect in the consultants’ mandate. Because any new ward structure is subject to an appeal to the Ontario Municipal Board, council would’ve left itself vulnerable had it appeared to be prejudging the outcome.

“We have not been told anything,” says Bowron, in response to a question from a meeting participant. “We have not been told even that we have the ability to increase or decrease or something. We are supposed to look at this completely objectively from the outside. So there haven’t been any instructions.”

Once the consultations wrap up later this month, the project team will hunker down and develop a series of options on which they’ll solicit feedback, including at a second round of meetings this fall. The final report, to include “a specific recommendation,” will go before council in early 2016, with a view to implementing the changes as of the 2018 election.

Asked how many or how broad a range of options they expect to present, Bowron says, “We honestly don’t know. We haven’t got a clue yet.”

At this point, the future of council remains open to suggestions.