I’m headed to the opening of Anser’s new show at #Hashtag Gallery. Twenty minutes after opening it’s already packed.

Established art buyers mingle with artists, art critics, and a mass of excited young fans. It’s a little overwhelming.

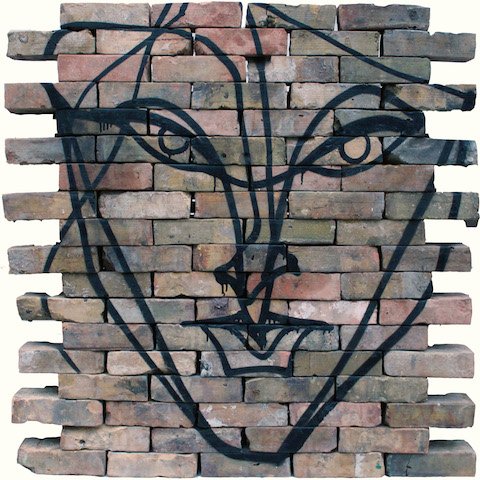

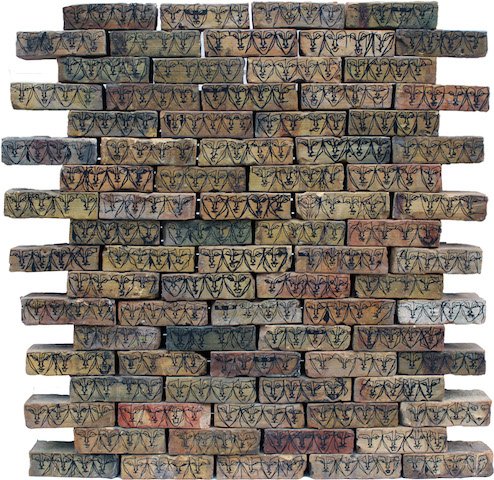

An installation of bricks bearing the artist’s signature graffiti face, Mysterious Date, hangs in the window. The graffiti bomb is one that Anser has painted on walls around the globe, from Shanghai to Montreal, New York and Berlin. On this night, it’s one of a number of pieces incorporating materials that have been recovered from demolition sites and abandoned factories across the GTA for the artist’s latest exhibition Surface Salvaged.

I catch up with Anser by telephone a few days later, the anonymous artist calling from an undisclosed location.

Easily one of the most iconic and prolific graffiti writers this city has ever produced, you can’t help but be struck by the sophistication of the artist’s ideas about the medium.

Q. Why do you paint a face rather than letter-based forms?

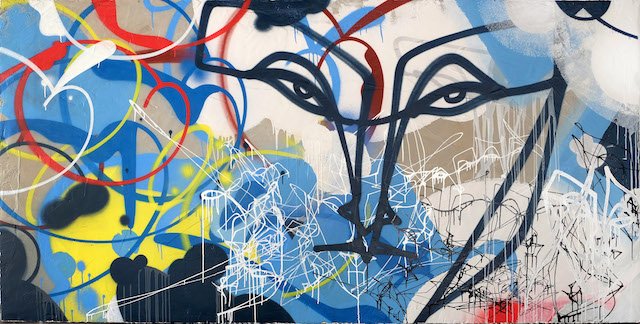

A. One of the major reasons I first started painting is because graffiti is very alienating – it’s difficult for the general public to feel any sort of connection to graffiti. It is largely coded letters created exclusively for other people in the graffiti community. Instead, I use the stylization that comes from letter-based graffiti art to create an icon that people can connect to. That is the power of an icon – its accessibility and the instantaneousness of the message and how easily the message can be communicated.

Q. Do you see graffiti art as vandalism?

A. There’s a constant battle going on within the graffiti world between those who do it for purely aesthetic reasons, such as street artists and muralists, and the more hardcore bombing graffiti artists who write graffiti purely for its destructive quality. But there is a kind of beauty in bombing’s destructive quality. I don’t know if everyone can be thrown into one camp or another, but there’s a definite war out there that’s happening. I don’t really see myself as a graffiti writer or a street artist. My work is very much about trying to bridge the two.

Q. Why do you think it’s important to appropriate private property for your work?

A. I do understand the legitimacy of owning property. But everyone has to interact in their daily lives with what’s around them in their physical environment. When you have a wall that’s facing a very direct and obvious route that everyone passes in their daily lives, that’s where the legitimacy of private property, to me, disappears a bit. I’m always baffled by why people care so much that someone is painting underneath some bridge that is very uninviting. Graffiti artists are trying to make it more beautiful.

Q. Graffiti is also a reaction to advertising culture.

A. You have advertisements everywhere trying to sell ideologies to us, and we have no way of saying what we want to see in public spaces. Graffiti is a way of taking that space back and having our own voice in the public realm.

Q. Can you explain the ways in which your work is consistent with the historical tradition of portrait painting?

A. The historic tradition of portrait painting always involved hierarchy and status. A historical portrait was a way for you to connect to an “important” person. That obviously changed with modernism and postmodernism, which used portraiture as a way to elevate the common person. The way I paint connects to the historic tradition in the sense that it still embodies an idea of connection to another person. I’ve taken away that element of status that defined traditional portraiture by painting images of everyday people and putting it on the streets.

Q. Any other influences with respect to portrait painters?

A. I love a lot of old portraiture. But I wouldn’t necessarily say that that’s where I pull from. I’d say my biggest influences have been other graffiti artists, especially growing up, and the stylization that happens in their letter forms. I took that letter-based style – especially focusing on the importance of the line – and applied it to my general affinity for portraiture.

Q. Recently you’ve been painting more faces wearing hoods. Why?

A. The hooded image was inspired by the death of Trayvon Martin. I was very moved by the power of that story, which to me was very much about how certain images are perceived in the public realm. I mean, it’s basically a kid who was shot because he looked “scary” or “dangerous,” and it’s all because he was wearing a hood and because his skin was a different colour. And I think that’s a very strong, powerful, and scary story that belongs in the public realm for people to reflect upon. It’s also a way of de-emphasizing the insidious aspects of anonymity. All across the world, including in Canada, we have these prejudices towards the way people dress.

Q. For many years you’ve also painted images in a niqab. Is the image about promoting tolerance for the other’s cultural and religious practices, or is your work a critique of the way in which the niqab is a symbol of oppression towards women?

A. When I started painting those I was not trying to make a judgment one way or another. It was more about creating it as a symbol of inclusivity, to reclaim space for images of women who have generally been barred from representation in the public sphere. I think generally that people should be able to wear what they want, but that there is also a highly oppressive aspect to this garb. To me, it’s less about making a statement and it’s more about raising the question. It’s less about finding a right or wrong, but about building a dialogue.

Q. Over the years, you seem to have begun painting more images of men and less feminine faces. Is there a reason for this?

A. I’ve always enjoyed how the face has become a little bit more androgynous. The androgyny is important because the image is no longer specific to one gender, so that anyone can apply what they want to it. It’s more about the public connecting to the face. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a man, it doesn’t necessarily have to be a woman. It can be any face. It’s more about creating a broad icon that anyone can connect to.

Q. Do you think there is a problem with the sexualized objectification of the female in graffiti?

A. Most definitely. That’s a huge thing within graffiti and street art. When I add a strand of hair that suggests a woman’s face, a lot of the time they are staring directly at you, almost confrontationally, and that, to me, takes away from the objectifying nature of the image.

People see an image of a beautiful woman and say, “That’s art.” And in a lot of ways that’s what’s been taught to us by the art market and the art world. Some of the earliest portraiture, a famous example is Johannes Vermeer’s Girl With A Pearl Earring, the main patrons used it as a way of possessing this beauty as a sexual object.

Q. Have you ever considered figure painting?

A. I really do think that there is this longstanding, voyeuristic view of objectifying the naked female body, and that’s something I don’t necessarily want to participate in.

Q. In many of your newer images, including in your new show, there are several faces that appear unfinished – a cheek missing here, part of a forehead missing there. Why?

A. I intentionally leave things out to allow the viewer to complete the image themselves.

Q. What is your reason for repurposing found objects for the graffiti images in Surface Salvaged?

A. It has to do with saving the history that’s there and saving the life of these objects. I feel as though there’s an essence within those materials – there’s an aura that comes from these objects that ought to be preserved.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Anser: Surface Salvaged runs until February 28 at #Hashtag Gallery (830 Dundas West).

news@nowtoronto.com | @nowtoronto