MUSSOLINI’S DAUGHTER: THE MOST DANGEROUS WOMAN IN EUROPE by Caroline Moorehead (Random House Canada, 432 pages, $25.95). Rating: NNNN

A century ago this week, Benito Mussolini and his fascists waged a coup d’état against the existing government and seized power in Italy. His firstborn and favourite child, his daughter Edda (1910-1995), became the model image of what a fascist woman ought to be, particularly after she wed Italy’s foreign minister Galeazzo Ciano. She was her father’s de facto “first lady,” because her reclusive mother, Rachele Guidi, flat-out refused to cop to such duty, frequently scorning her philandering, fanatical husband.

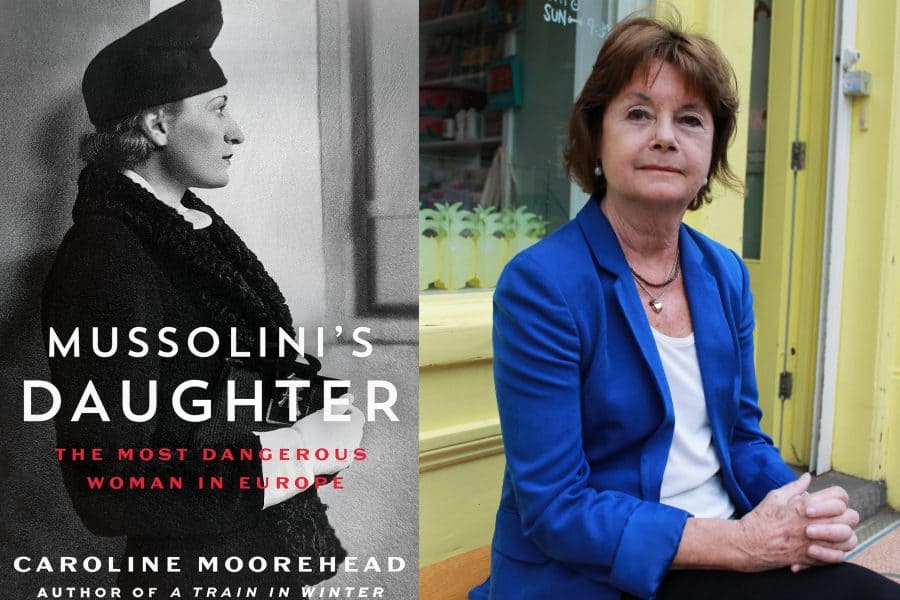

Esteemed biographer and historian Caroline Moorehead (Bertrand Russell: A Life, A House In The Mountains: The Women Who Liberated Italy From Fascism) creates with her trademark narrative elegance and authoritative attention to detail this portrait of a complicated, at times cruel, woman.

She tells us that at just nine years old, Edda was already “like her father, passionate, jealous and possessive, unpredictable and volatile.” It is no wonder that her time at Italy’s most prestigious school for girls – Istituto Femminile della SS Annunziata in Florence – was a complete disaster. At 15, she was miserable, fighting with her classmates and teachers. When her father agreed to remove her, “no one was sad to see her go.”

In 1929, shortly after Edda married Ciano, her father named him Consul General of Shanghai, and the newlyweds moved there for three years, in what Edda considered “a miraculous escape from everything now expected of them in Fascist Italy.” In 1931, Edda gave birth to her first child, Fabrizio, a son who seemed “worryingly quiet and floppy” until she discovered his wet nurse had been giving him opium. Like her father, Edda’s husband was a serial philanderer, and she responded by openly flirting with handsome younger men and by gambling recklessly.

Mussolini recalled the pair to Rome in 1932, where they were expected to publicly preen as the ideal fascist couple: “dutiful, efficient, moral.” It became clear that Edda was the only child of Mussolini’s to treat him like an ordinary father, “challenging his assertions and disagreeing with his opinions.” She was fascinating to journalists because she was “wilful, rebellious, odd and restless.” Yet she was also self-aware. By mid-1930s she told a friend, “We must deprive ourselves of nothing, because we know that the guillotine awaits us.”

After Ciano was made Foreign Minister, Edda traveled frequently on diplomatic missions to Germany, where she met all of the leading Nazis: Hitler, Goebbels, Goering. And once Germany was at war, she encouraged her father to support them, while her husband wanted to avoid such an alliance, complaining that his father-in-law wanted war “like a child wants the moon.”

“Emergencies brought out the best” in Edda, notes Moorehead. For example, after training as a Red Cross nurse, she served on a hospital ship headed for Greece in March 1941. When it was torpedoed, and Edda survived in the icy water, clinging to a life preserver for hours, instead of panicking she looked at the moon, “thinking that it was bright enough to read a newspaper by.” And in December 1942, when she went to Sicily to see firsthand the chaos and misery, she wrote to her father, “They are dying of hunger and cold. Literally… What they are saying here is that the Duce doesn’t know. But now you do know.” As one journalist wrote, “Everyone knows that her father rules Italy and Edda rules her father.”

In July 1943, at a fascist council meeting, Ciano was one of many members who voted against Mussolini, who, as a result, was spirited away and temporarily imprisoned on the island of Ponza, where Hitler sent him the complete works of Nietzsche. German paratroopers rescued him and installed him as a puppet dictator in northern Italy. Ciano himself was arrested and imprisoned in Verona and executed in January 1944. As Moorehead observes, “Mussolini had effectively killed the husband of the child he loved.” Edda, for her part, was heard to say to her father: “It’s all over between us, finished for ever, and if you were to kneel before me dying of thirst, and beg me for a glass of water, I would pour it out on the ground before your eyes.”

Engrossing and enraging, Mussolini’s Daughter is in the end a balanced portrait of a woman who not only benefited from fascist crimes but was also a victim of them. With last month’s election of the far-right Giorgia Meloni as Prime Minister of Italy, it is not easy to forget the fascist Mussolini years and what her leadership might portend. And with the rise of homegrown fascism threatening democracies from Hungary to the United States, attention must be paid to the horrors of the not-so-distant past.

Janet Somerville is the author of Yours, For Probably Always: Martha Gellhorn’s Letters Of Love & War 1930-1949, available now in paperback from Firefly Books, and from Penguin Random House Audio, read by Tony Award-winning Ellen Barkin.