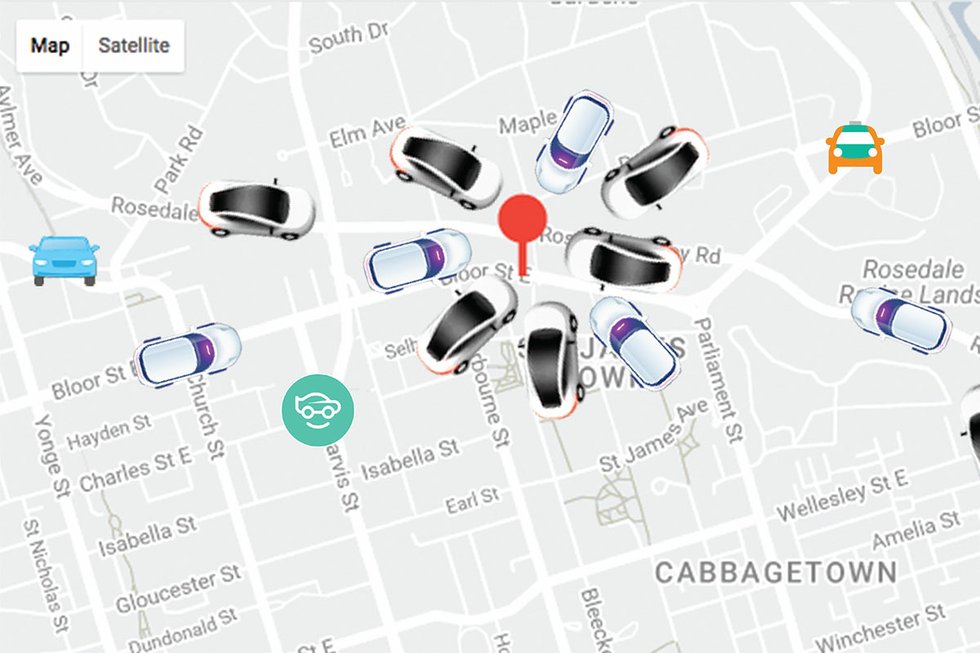

When a power outage knocked out subway service on the Bloor line last week, Uber did what Uber does. The ride-hailing giant ratcheted up surge pricing, to a flurry of angry tweets.

Of course, Uber is used to being hated on. The Twitterverse was ablaze with #deleteuber hashtags virtually every week of 2017.

Now, a year after hundreds of thousands of Uber users ditched the app after its drivers continued operating during taxi driver protests against President Donald Trump’s first attempt at a travel ban, Lyft and two other ride-hailing apps have answered T.O.’s call for a new ride.

Those of us who’ve scrubbed Uber from our phones want to know, are Lyft, and new options InstaRyde and Facedrive, really more ethical?

America’s second-largest ride-hailing app is angling itself as “a better boyfriend” – the kinder, socially progressive alternative to its scandal-plagued rival. Its 33-year-old president, John Zimmer, told Time last winter, “We’re woke. Our community is woke. The U.S. population is woke.”

To prove it, Lyft pledged to donate $1 million to the American Civil Liberties Union over the next four years to help fight Trump’s travel ban and defend the constitution. Three months later, Lyft started allowing passengers to round up fares to the nearest dollar and donate the cash to orgs like the ACLU, World Wildlife Fund and Girls Who Code.

A Lyft rep tells NOW that since May over $2 million has gone to charitable causes and, as of this month, the company will allow Canadians to round up and donate to Sick Kids hospital.

Of course, it’s hard not to look shiny when parked next to Uber. Besides a string of privacy violations (including “spying” on Beyoncé) and last week’s US$3 million settlement to New York City drivers for docking excessive fees from their fares, Uber headquarters has been known for its misogynistic “trickle-down asshole” culture. Sexual harassment complaints by one former Uber engineer led to the firing of over 20 employees, and Uber drivers seem to be enmeshed in one high-profile sexual assault case after another.

Last June, bro-in-chief Travis Kalanick was forced to resign from the company he once creepily nicknamed Boober, the same week Uber’s marketers embarked on “180 days of change.” By November, the company pledged $5 million to seven orgs working to prevent sexual assault. But in the two months since, another dozen drivers have been accused of sexual assault in the U.S. alone.

Uber Canada rep, Susie Heath, tells NOW that “while Uber has revolutionized the way people move in cities around the world, it’s equally true that we’ve got things wrong along the way.” She adds the company will now “run our business with humility, integrity and passion.”

To be fair, Lyft isn’t always a progressive bastion. It, too, has had plenty of sexual assault claims against drivers. It also fought against unionization in Seattle. It’s got a handful of Trump pals as major investors (namely Peter Thiel and Carl Icahn).

During the power outage on January 8, Lyft slapped steep surge pricing on stranded Torontonians as quickly as Uber did. And on driver message boards you’ll find complaints against both companies, though so far, Lyft drivers have a better retention rate than Uber drivers according to app-use analyzers at Apptopia.

Unlike Uber, which fuelled a no-tip culture until it added a gratuity function in June, Lyft has always allowed passengers to tip drivers in-app. Lyft reps tell NOW that to date, drivers have earned over $350 million in tips.

While some polls say Lyft drivers can earn about $2/hour more than Uber, transport planning expert and associate prof at Ryerson’s Ted Rogers School of Management Murtaza Haider isn’t convinced that tips and charitable donations are enough to make Lyft an ethical option.

Haider, who authored a paper called To Uber Or Not To Uber, says the problem is that Lyft’s fundamental business model remains the same as Uber. Both offer mostly part-time gigs (which half of drivers bail on within a year), while an entire sector of professional working-class cab drivers is being, as he puts it, “decimated.”

“The question,” Haider asks, “is which option is better for society: to create a class of workers who struggle to live while you and I benefit from a ride that is a couple of bucks cheaper, or do we [support] people who provide essential services to us and are able to earn a living wage while doing so?”

Trouble is, nailing average driver incomes for cabbies or ride-hailing is tricky. Last checked, StatsCan found that full-time cabbies in Toronto made around $21,680 a year in 2010, after expenses. Hardly a living wage, but since Uber added 50,000 registered drivers to the road (and most averaged just $3,125 during the company’s first year in Toronto), one iTaxiWorkers Association rep says that cabbies have seen their income slashed in half and that Lyft will slice up the pie even further.

iTaxiWorkers Association’s paralegal Patricia Reilly says the city was already oversaturated with 5,000-plus cabs on the road. “Now it’s 55,000 people sharing the same pie.”

If you’re in the “adapt-or-die, cabbies” camp, Haider suggests considering the planetary impacts of your Uber habit. It’s one thing if you’re using Uber or Lyft’s carpooling features instead of taking a cab, but what happens when ride-hailing replaces a trip on transit? The most comprehensive study of ride-hailing impacts in seven U.S. cities, released by University of California Davis Institute of Transportation Studies last October, found half of ride-hailing trips are ones that would have been made by walking, biking, transit or avoided altogether.

“Would that be ethical in terms of emissions and pollution and congestion on our streets?” asks Haider. “How is it good for society?”

Councillor Glenn De Baeremaeker has been on the city’s licensing committee for nearly a decade and is a vocal Uber critic. “I don’t think Lyft is going to be a kinder, gentler app,” he says. “They’re really not doing anybody any favours.”

Especially since ride-sharing companies don’t face the same restrictions on gas-guzzling vehicles that cabs do. While the city requires all ride-hailing and cab vehicles be no more than seven years old, cabs must have a fuel efficiency rating of at least seven litres per 100 kilometres to help meet Toronto’s climate action plans.

One new Toronto-born ride-sharing app, Facedrive, pledges two cents to Toronto Parks and Trees Foundation for every kilometre ride in one of its gas cars, and offers discounts to electric and hybrid drivers, which is cool.

But with limited numbers of drivers, hailing a ride took me dozens of glitchy tries over two weeks shortly after its launch. It’s also too bad Facedrive’s website overstretches its cred by promising “emissions-free” rides (most of the cars are gas-powered) and a workers co-operative structure. (It’s not a registered co-op, but promises drivers 33 per cent profit-sharing at year’s end.)

Regardless, De Baeremaeker adds that traditional cabs are just plain safer since they now have to be outfitted with cameras. That’s not to say cab drivers haven’t been accused of sexual assault, but it would be nice to see Uber, Lyft and the rest get behind mandatory dash cams. However, Toronto does screen drivers for criminal records, driving history and insurance.

Either way, ask rides-hailing users and they’ll tell you Toronto cabs put a flat in their own tire by charging more than other major cities like New York. Isn’t our archaic, middleman-heavy licensing system undermining driver salaries and inflating rider costs?

“That’s factual,” says Reilly. But, she adds, “That’s a governance issue. That comes out of city hall. They determine what those meters start at.”

These days, meters start a buck lower than they used to, and cab licence rental rates have come down, while Uber prices have risen. That means if you’re chasing the cheapest ride, cabs, Ubers and Lyfts are often around the same price (depending on surge rates, at least).

Enter local newbie InstaRyde, which claims to offer the most affordable option for consumers and the fairest app for drivers by taking just 99 cents off the driver’s cut rather than the 25 per cent plus commission pocketed by Uber and Lyft. InstaRyde, like Facedrive, has yet to tack on surge pricing, which should win over some riders. But amidst the early January power outage, you couldn’t hitch an InstaRyde if your life depended on it. Drivers (who tend to clock onto multiple apps at once) picked up Uber and Lyft riders first to capitalize on the mega-surge in fares. Reps say InstaRyde may soon introduce “dynamic” pricing to retain more drivers.

Expect the market to get even more muddled when Europe’s Taxify rolls out in Toronto this month. It too claims to be cheaper and more ethical than Uber. And if the iTaxi Workers Association manages to launch its own registered co-operative app for beleaguered cabbies mid-March, it may officially win the fairness prize by offering, as Reilly says, “lower-priced fares in a safe environment, with highly trained professional taxi cab operators.”

Or, you could just use one of the city’s current cab company apps.

As to whether any of the indies can afford to go head-to-head with Uber for long, it’s anyone’s guess. The only sure thing is, if we really want to ride the most ethical option, we should probably just wait for the streetcar.

Ride-hailing vs Ride-sharing

Think Uber, Lyft and friends are ride-sharing services? The European Union’s Court of Justice ruled last year that Uber is a transportation service – not ride-sharing. The Associated Press Stylebook for journalists also considers the word misleading and, in 2015, started instructing journos to use the term ride-hailing instead, which, you know, has nothing to do with genuinely uncommodified sharing. So if you get paid by Uber to drive people around in your car and call that sharing, you’re “share-washing,” honey.

Cost vs Price

What is the true cost of ride-hailing? Depends how you calculate environmental and social impacts. As for the fare? Well, final prices and quotes vary wildly depending on surge pricing, traffic and driver distance. Wait times vary heavily, too, for smaller companies like InstaRyde and Facedrive. But for an off-peak 6.5-kilometre ride to the downtown core pre-tip, here are the fares NOW was quoted:

Cab: $22

Uber: $15.66

Lyft: $15.85 (quote was $35 during rush hour three hours earlier when a cab would have been much cheaper)

InstaRyde: $13.28 (fair estimate was $8-$11, plus service fee & tax)

Facedrive: $16-$26 (estimate varies since closest driver was 15 minutes away and the driver gets paid to drive out of his/her way to pickup location. If the ride started downtown going in the opposite direction, estimate is $10-$23 with a one-minute wait time).

ecoholic@nowtoronto.com | @ecoholicnation