ROOTS OF THE 6IX: MAESTRO, MICHIE MEE, DREAM WARRIORS, DJ RON NELSON as part of CANADA DAYS at Nathan Phillips Square (100 Queen West), July 2, 3-11 pm. Free. See listing.

“Toronto’s Apollo,” “a mini-Caribana,” “the matriarch” of Toronto’s hip-hop scene.

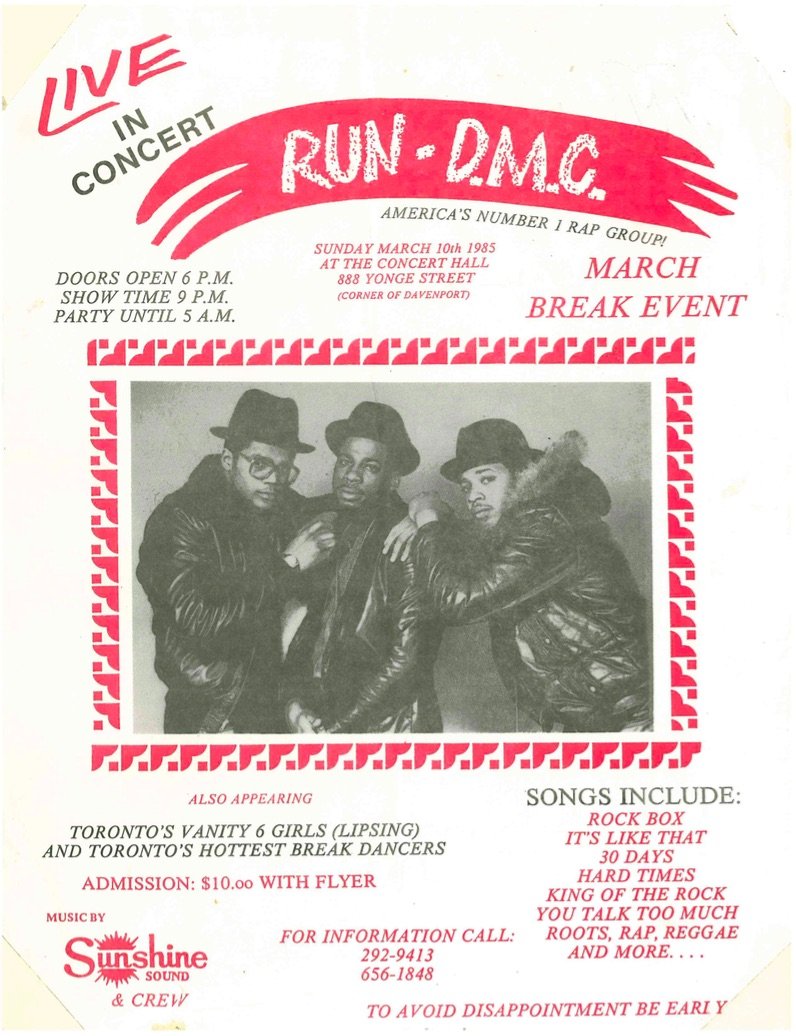

Storied live music venue the Concert Hall is most often associated with 60s rock acts like Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones. In the 70s, 80s and 90s it was the place to see punk, new wave, funk, dancehall, reggae and grunge.

Much less talked about in mainstream media is the pivotal role the 100-year-old venue at 888 Yonge played in laying the foundation for Toronto’s currently thriving hip-hop scene.

In the 80s and early 90s, hip-hop parties were dispersed around suburban neighbourhoods in community halls, schools, basements and rental places. The crowds and musicians were young, primarily Black first- and second-generation Canadians. But as the scene grew, the venue housed in the centrally located Masonic Temple at Yonge and Davenport became hip-hop’s mecca.

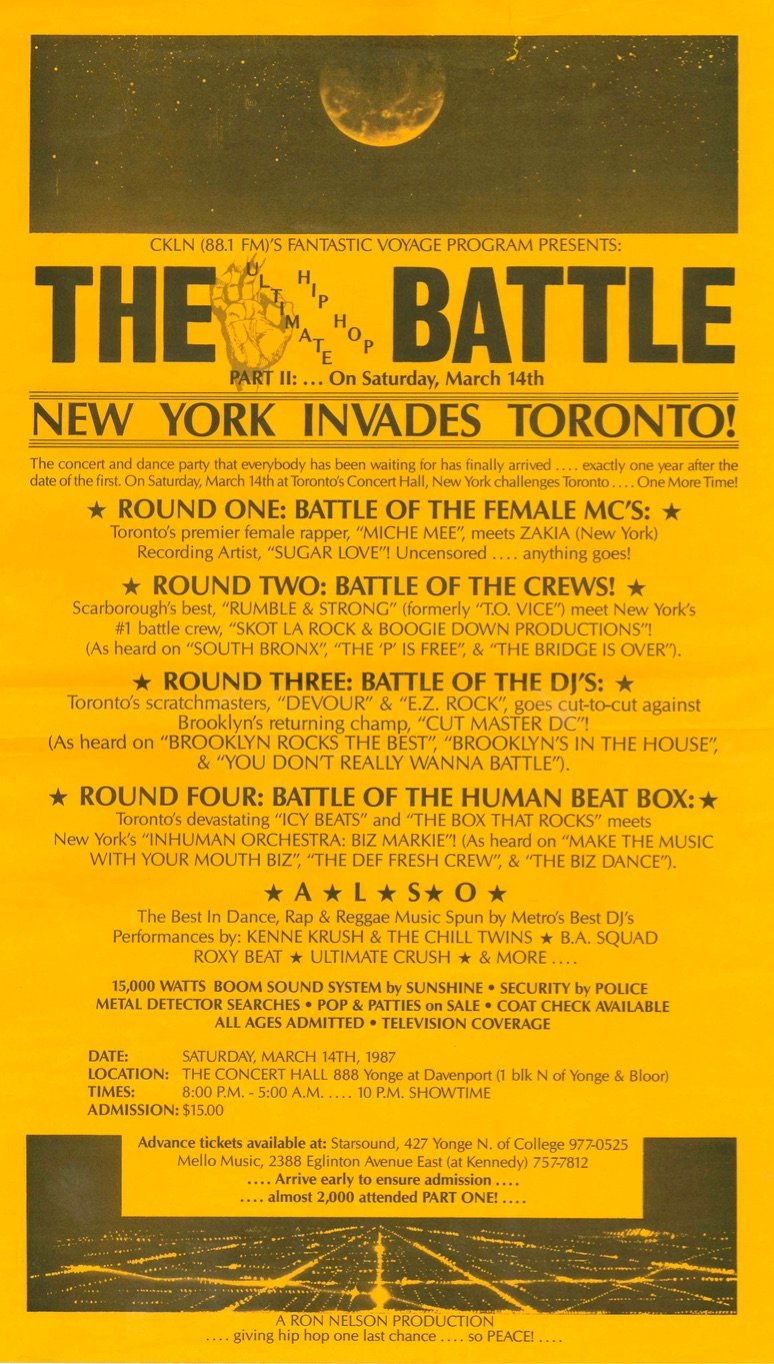

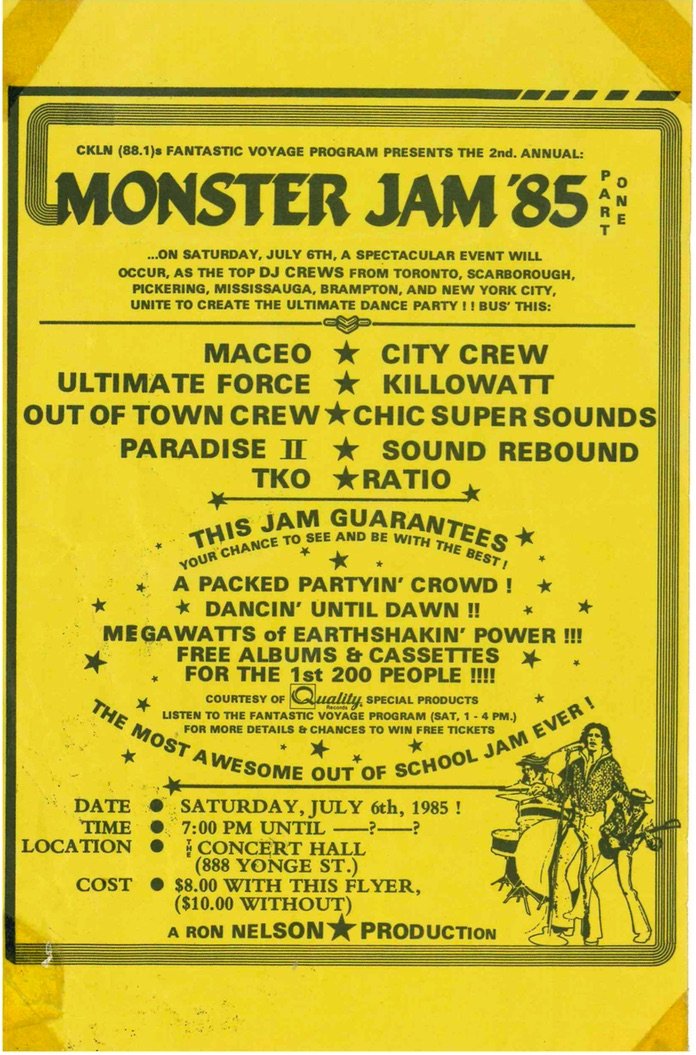

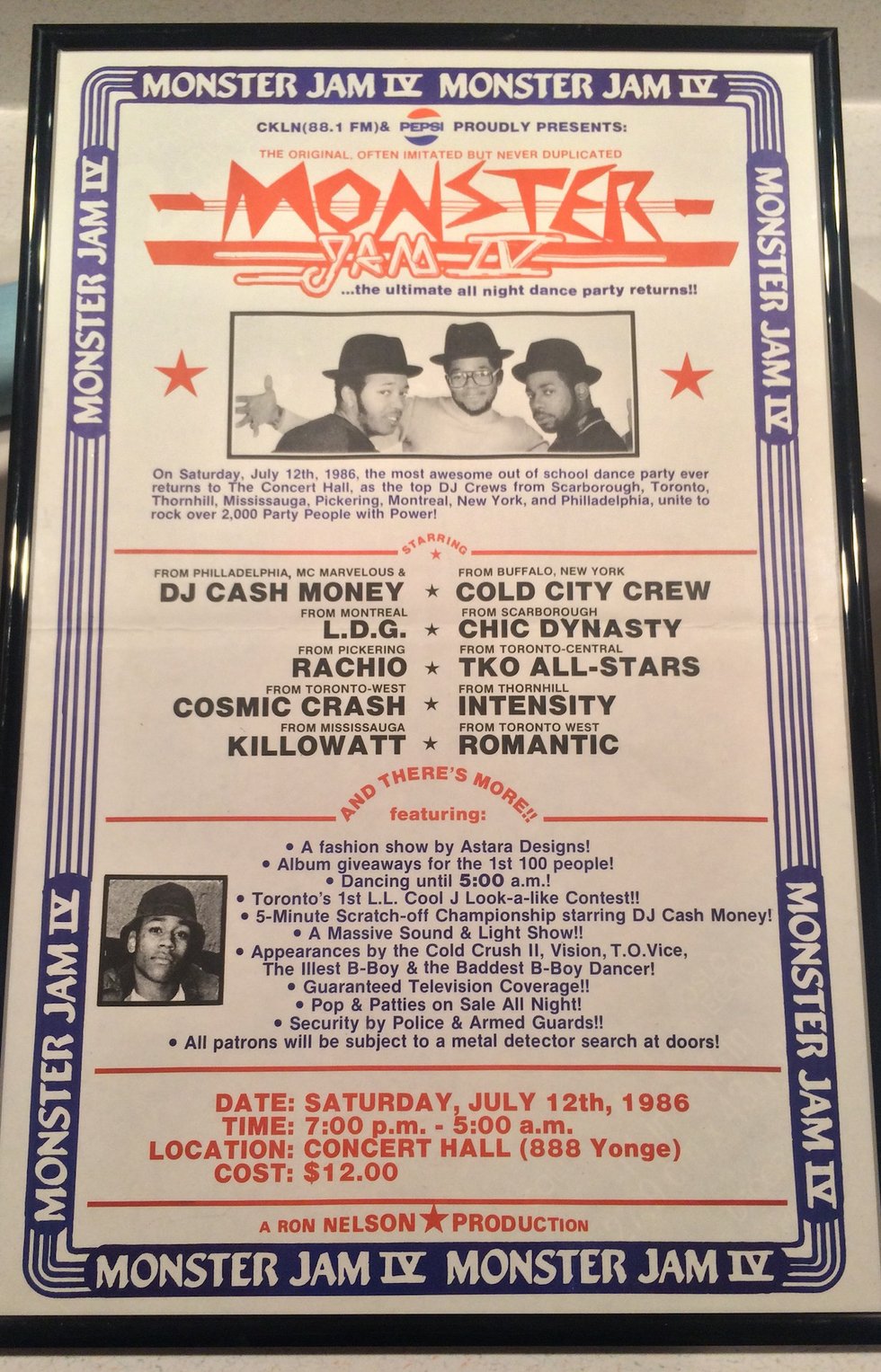

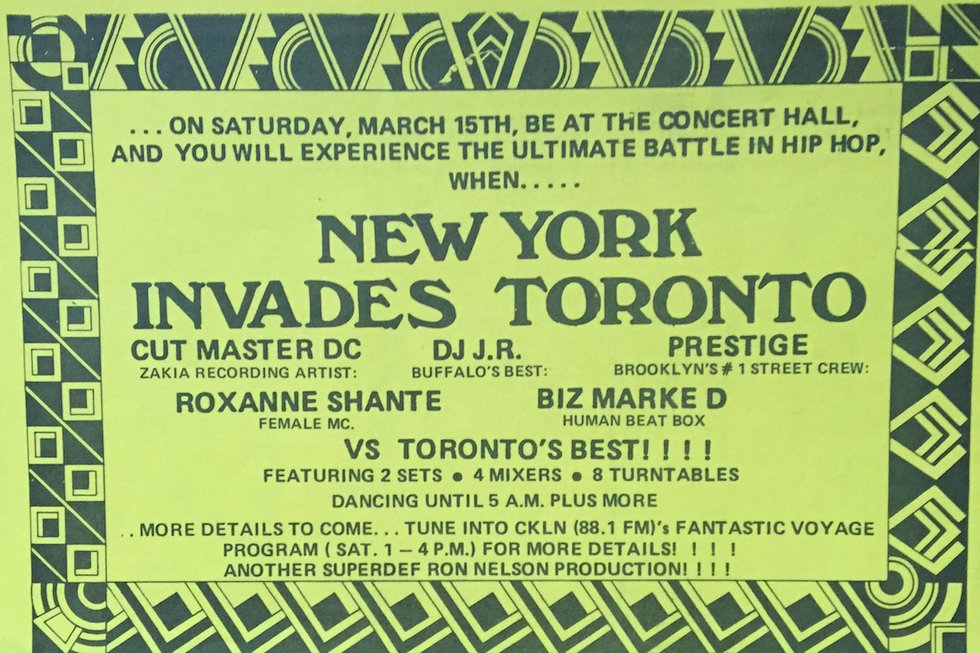

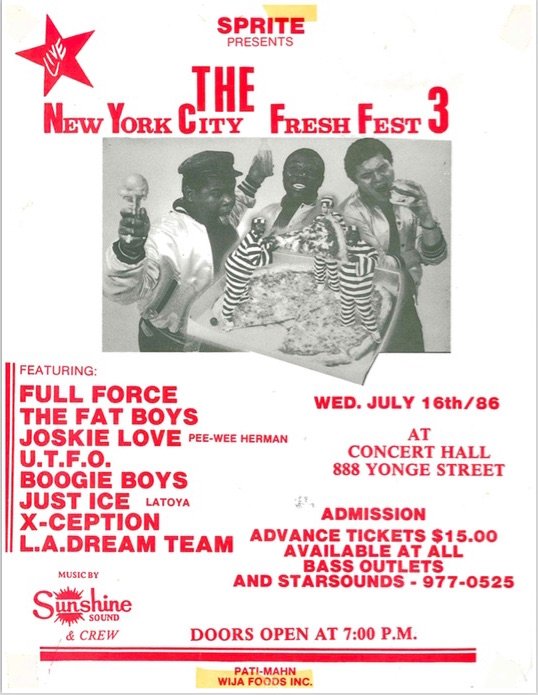

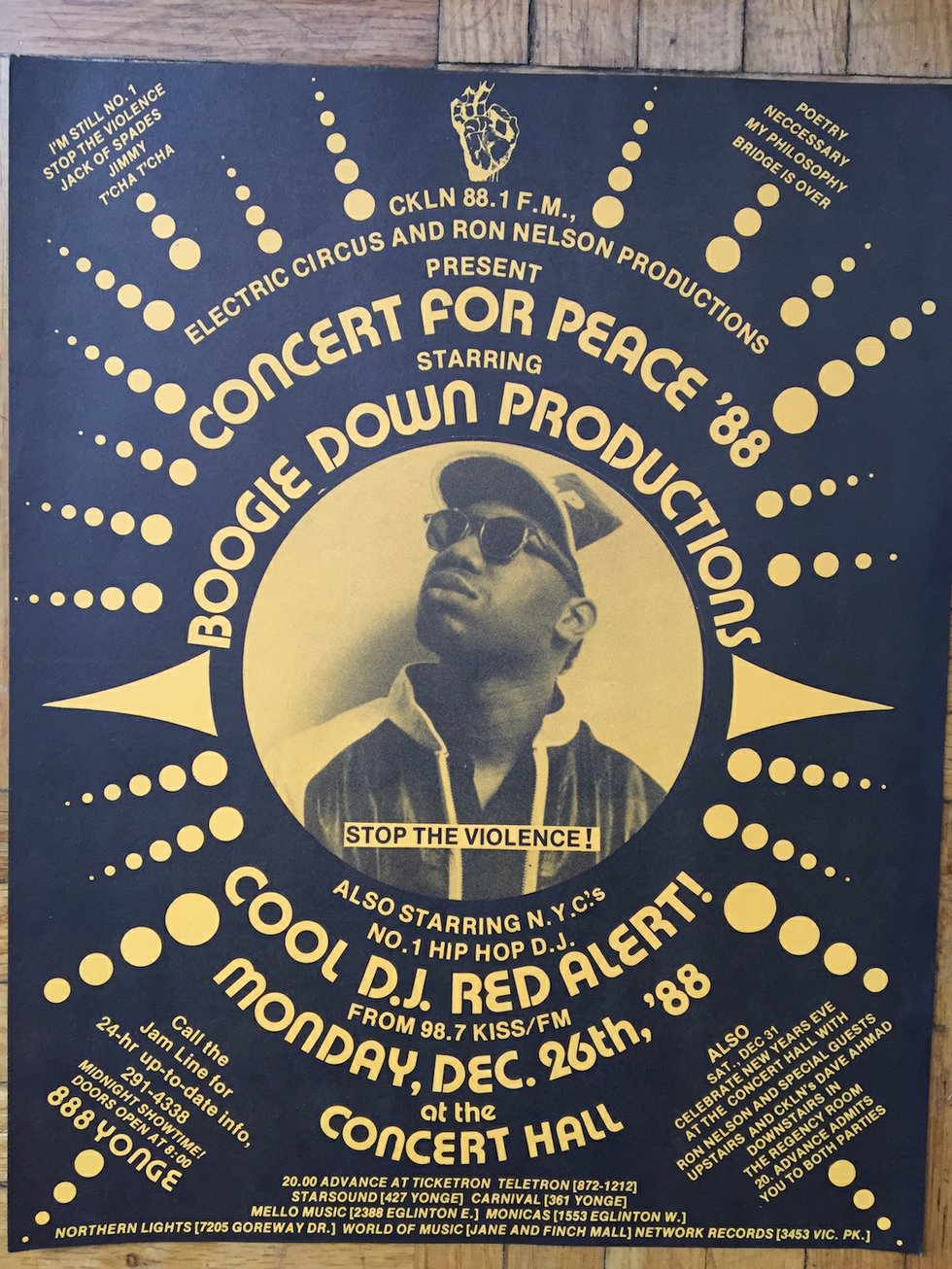

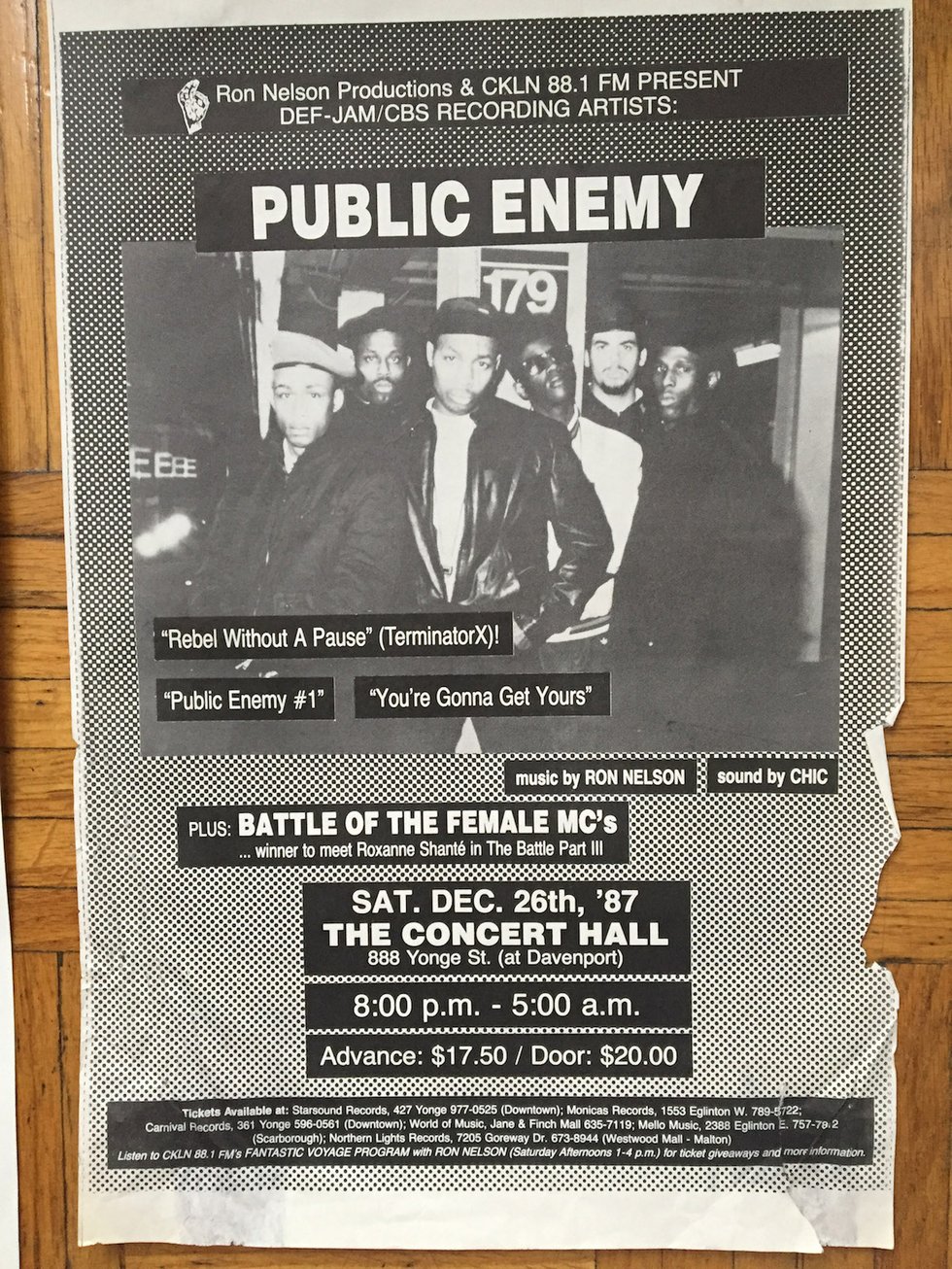

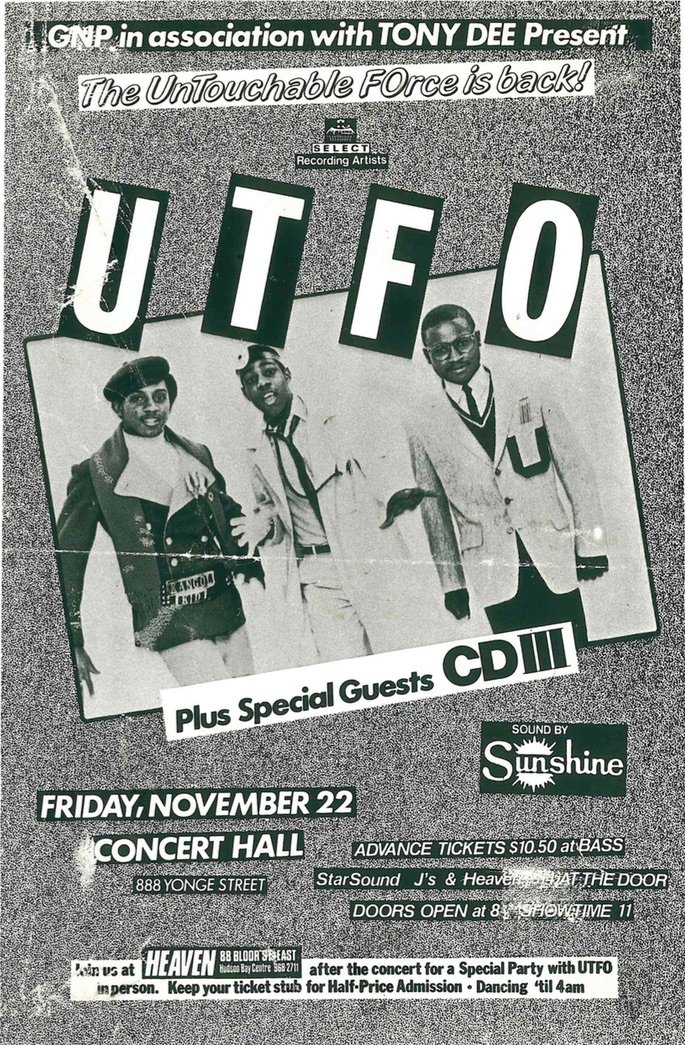

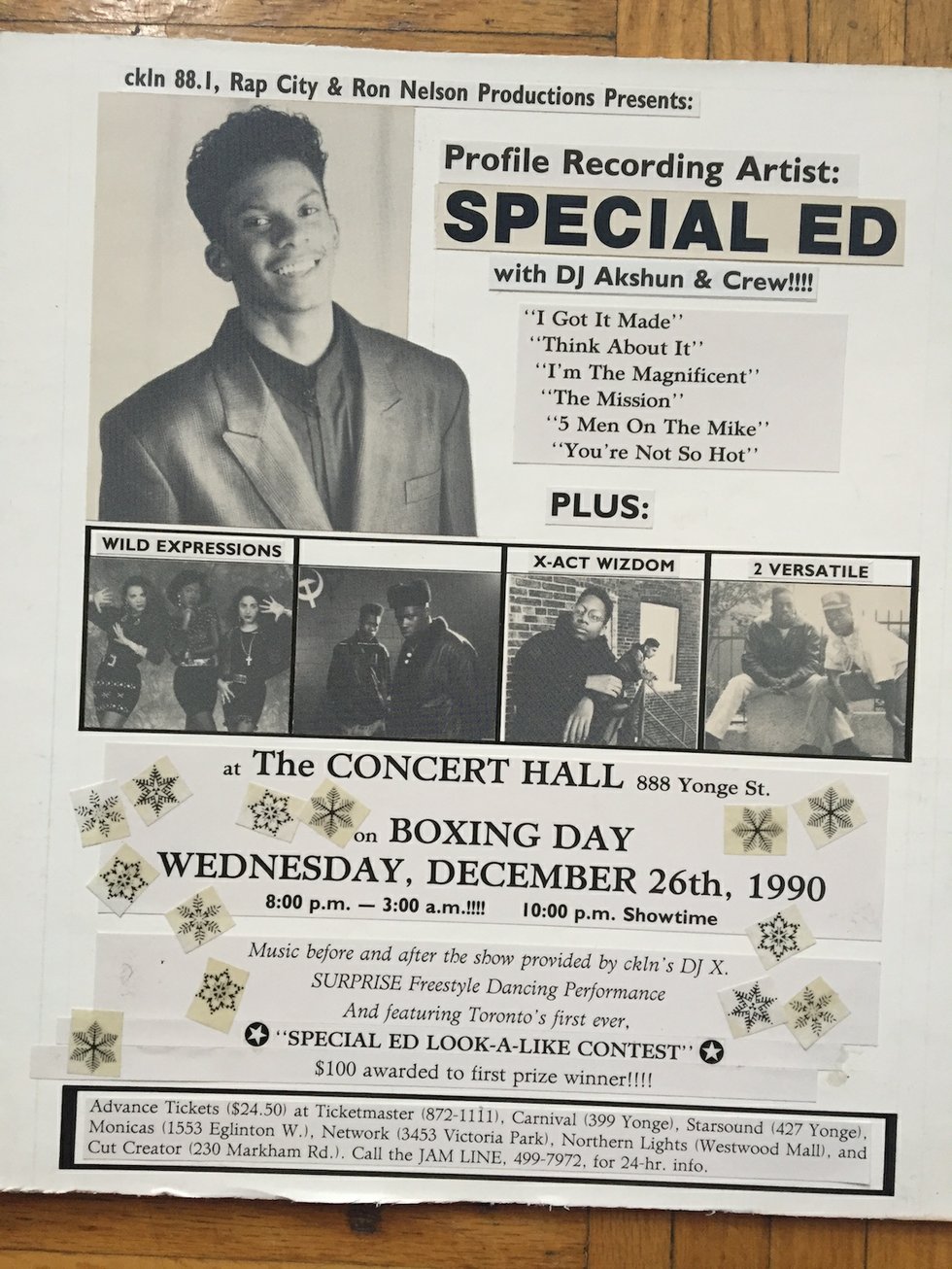

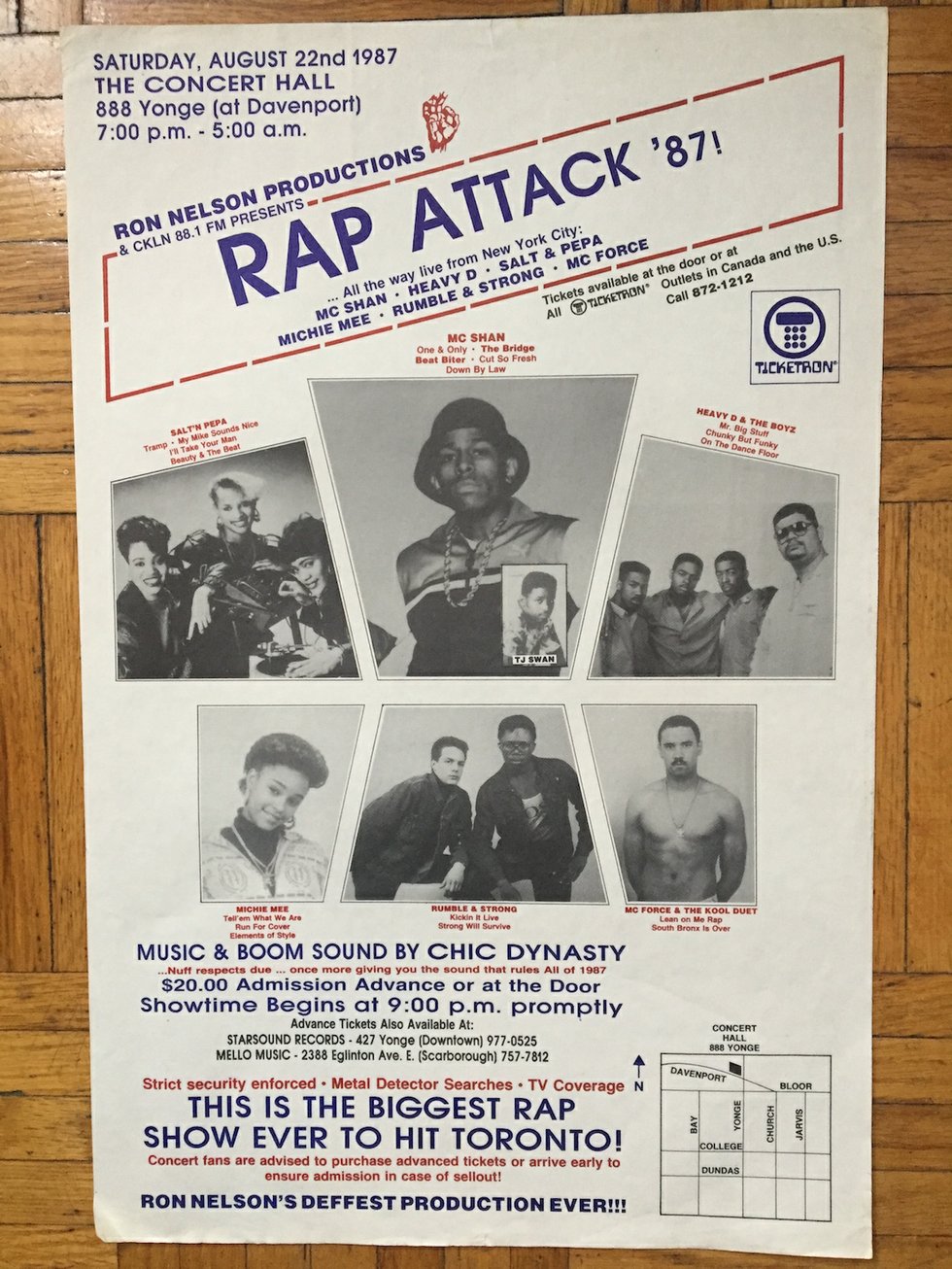

CKLN radio host and DJ Ron Nelson was the best known hip-hop promoter in the 80s, responsible for bringing Public Enemy, Boogie Down Productions, Roxanne Shanté, Salt-N-Pepa, Eric B. & Rakim, Ice Cube and Queen Latifah to town. Hip-hop shows had happened at the Concert Hall prior to Nelson’s first show there, but he took the scene to a new level with multi-artist bills and rap battles between Toronto and New York artists.

Maestro, Michie Mee, Dream Warriors and many others established themselves on its stage, while the sound was supplied by sound systems and DJ crews like Sunshine, Kilowatt Sound and Chic Dynasty.

The confluences of these artists and sound systems also laid the groundwork for the mixing of hip-hop and dancehall that helped set Canadian rap apart from the New York scene. The sound has evolved into a chart-topping force thanks to hometown superstar Drake.

The Masons owned and managed the building until financial troubles led them to sell it in 1994. Nelson left hip-hop and moved into reggae/dancehall promotion with his company Reggaemania. Meanwhile, the building’s new owner failed to win city approval to redevelop it into condos. CTV scooped up the property in the late 1990s and later operated MTV Canada there, before London, Ontario-headquartered Info-Tech purchased it in 2013.

Info-Tech is installing a new sound system and relaunching the Concert Hall as a venue during Toronto Jazz Fest later this month. In anticipation, NOW spoke with artists, promoters and hip-hop fans about one the Concert Hall’s most enduring legacies.

The biggest stage in hip-hop

Christopher “Thrust” France, rapper: The Concert Hall was like the Apollo of Toronto. That stage made every prominent artist in our scene. If you couldn’t perform at Concert Hall, then you couldn’t get the stamp of approval from the city.

Motion (poet/MC/broadcaster): Hip-hop was very much an underground culture in Toronto at the time. The Concert Hall provided the space for people to come together and assert who they are, what they love and show how big the Black and people of colour community was across the city. It was key in growing the culture.

King Lou (artist/Dream Warriors): It was like a mini-Caribana. The Concert Hall became the ideology of growth for people in project neighbourhoods. That’s where we all went to meet other people like us from other environments.

Michie Mee (artist/MC): If Concert Hall was a girl, it’d be the matriarch of our scene, of our family.

Paul “Mastermind” Parhar (DJ/broadcaster): There was nothing glamorous about the venue. I was 13 or 14 at the time, and it was a little scary because the crowds were huge and obviously older. But once we got inside, we would just go upstairs and sit on the padded seats.

Jonathan Ramos (promoter, Ink Entertainment): Ron Nelson was the epicentre of that whole hip-hop scene. Not only was he the biggest and most reputable promoter, he was also a DJ and hosted the biggest radio show, Fantastic Voyage, on CKLN, from 1 to 4 pm on Saturdays. The entire scene revolved around college radio. CIUT and CHRY also had shows.

Kardinal Offishall (artist/MC/A&R exec, Universal Music Canada): I was a kid so Concert Hall was this mythical place where hip-hop existed. They would do an audio recap of the week before during Ron Nelson’s radio show. I can still see myself sitting in my living room listening to what happened at Concert Hall. The Choclairs, the Socrateses, Kardinals – we were influenced by Concert Hall in an aspirational way. You lived your life hoping one day you’d be able to rock that stage.

Ron Nelson (promoter/broadcaster): I was basically the first radio DJ-celebrity who also had the ability to play out live. I was booked because of my notoriety.

Hip-hop was so new, there weren’t a lot of promoters doing concerts. When things got elevated to a point where you needed a venue that could hold between 1,000 to 2,000 people, there wasn’t really much choice.

Ramos: Nobody wanted to give hip-hop promoters Friday or Saturday because the events were all-ages and there was stigma about violence. So concerts always ended up in non-traditional spaces. There was a place on Church Street called the Party Centre, but the bigger shows were at the Concert Hall.

Nelson: The all-ages thing was part of the reason why the whole thing worked. It allowed everyone to gather in this venue that was centrally located, and it wasn’t all about selling alcohol to divide up the people who were most enthusiastic about this uprising culture.

Dalton Higgins (publicist/author/journalist): Hip-hop back then was about crews. You’re from Flemo – Flemingdon Park – or from Jungle – Lawrence West – Regent Park or Marlee Avenue. There was always this thing about staking out territory.

Thrust: Concert Hall was really the only large place that would rent to a Black promoter on a regular basis. It was the best because it was right downtown, and downtown was the middle ground.

Craig Mannix (A&R manager, Sony Music Entertainment Canada): In the 80s, the music scenes were much more segregated [than now]. You were either a b-boy or a punk or a mod or a rocker. Everybody had their categories.

Capital Q (artist/Dream Warriors): All the dancers would go down for the concerts because of the possibility of having battles on the floor beforehand. If there was a dance-off in a neighbourhood beforehand, you knew there was a possibility [the dancers] would meet at this concert.

King Lou: Once you went there, you knew right off the bat where certain guys were from. A downtown person, that’s different from a Scarborough person, that’s different from a west-end person.

Nelson: [The Masons] needed to make money and they weren’t judgmental. They basically let in anyone who seemed to have their ish together and presented themselves as promoters with potential. They gave everybody an opportunity.

Ivan Berry (manager/cofounder Beat Factory Records): Where else were you going to get 2,000 people – the entire hip-hop community – screaming, yelling and dancing at your act because they were there with Biz Markie, Scott La Rock and KRS-One or Public Enemy. As a platform it was massive.

Thrust: Our scene at the time was 95 per cent Jamaican – Jamaicans who were into this new thing call hip-hop. But they still had a Jamaican attitude, which is like, “If you ain’t doing it, we don’t want to see it.”

Motion: As an artist, that was the stage you wanted to conquer. You wanted to be able to say, “Yeah, I did it.”

Michie Mee: It was raw energy. If we weren’t good, they would boo us. It was, “Let me tell you who I am,” and you had to prove it and perform it. You had to act like you had a stylist, because these were the days before stylists. You had to have your hair done. You had to know who you were in order to sell to that crowd, because they weren’t taking BS from anywhere.

Higgins: I saw bottles being thrown, food, miscellaneous items.

King Lou: We didn’t have a lot of money to go out and buy expensive outfits that the Americans would be showing in their videos. Fashion went hand in hand with hip-hop. We would draw, colour and paint on clothes. All these things became expressions. No stores made it – we made it. “Next time you come up, bring me your graffiti jacket and I’ll pay you for it.” It became a meeting place for all different reasons. There was no internet to advertise your stuff.

Higgins: As a child, I didn’t really know what the Masonic Temple was but there were always a lot of rumours in the community about evil things. We never went up on that top floor.

Mannix: I would help set up for parties and I remember stumbling upon the ceremony room and that freaked me the hell right out. There were cloaks hanging on the wall, pentagrams and goat heads. It was weird. As a young kid, I was shook.

Nelson: I was seduced by people who had money and wanted me to take it to that next level. The very first time I did the Concert Hall, one guy who I thought was a pimp and another guy who was my head of security had financed the first Monster Jams. It was a hip-hop showcase of sound systems and eventually artists.

Mastermind: I met Ron at the radio station and became part of his street team. He was way ahead of the curve when it came to promoting. Because we helped him, he would give us tickets, and that’s all we cared about. We weren’t doing it to get paid.

Thrust: Ron promoted his concerts the way labels started doing street promo. It was planned months in advance. We had a grid of the whole city and went from the east and to the west end. We met up downtown to get flyers and hit every major bus stop where high school kids were.

Ramos: I grew up in Brampton. We’d always make the trip downtown, but you took your chances. Would the artist shows up? Would they get paid? Would security be proper? Or the artist would perform for 15 minutes, and it’d end in fights. That’s where Ron came in. I can’t think of a show where Ron never delivered [unlike other promoters].

Mastermind: If it was on the flyer, it happened.

Story continues below…

For more vintage Toronto gig posters, read about Instagram account The Flyer Vault here.

The front steps and the back door

Nelson: To do a Concert Hall event, sometimes you were looking at $8,000 dollars and up. The sound systems were paid $500 each.

Mastermind: I watched what Ron did – the people he hired, what he got those people to do and how he ran security, how he ran his door. He had his parents selling patties and pops. He was also the DJ and the host. DJ X, a protégé of Ron’s, ended up taking over the reins as far as DJing to give Ron more flexibility to run around.

Nelson: I hand-picked and trained my security people. You had to make sure they arrived on time, and by the end of the night you prayed to God everything went as planned – and that nobody robbed you. I had a giant safe I brought with me to lock the money in. You had to do everything yourself. My parents served the food. We had long lineups and we’d go through a hundred dozen patties in one night.

Mannix: There was always a huge crowd outside and a lot of pushing and shoving. The coat check was always a thing.

Motion: The energy started before you even got to the front door. Those steps that led up to the Concert Hall would be full of people, going down the sidewalk into the street. The anticipation built as you tryna get into those two front doors – or the back door, depending on how you rolling.

Michie Mee: As soon as you came out the subway, you’re looking to see how long the lineup is. Who’s at the back door? I loved the back door because I was always one of the cool girls who could get in.

Nelson: The back door was where the gangs would terrorize my events by gathering up in that area and trying to break in. If somebody opens that back door for Michie Mee, then all of Regent Park is gonna jump in.

Mannix: Of course you had your tensions, but back then there was no gunplay. You had your odd fight with fisticuffs.

Nelson: When people line up to get into the Concert Hall, by law they have to line up on Yonge Street going north. When they started to get out of control and gather around the doors, it became a big problem for security, and then the police came into it. I had so many meetings with police regarding the Concert Hall. I had to go to court when they accused me of selling liquor, which I never did.

Mannix: Chic Dynasty were a sound system that also rented out their equipment for parties and events. You’re talking about hip-hop and reggae, so you better have that bottom end.

Paul “Mistaboxx” Jarvis: First time I heard Biz Markie beatbox on the Chic Dynasty system was earth-shattering. Whenever Ron would get on the mic, he’d make a comment about Biz blowing the speakers.

Thrust: When you came out of the subway you would hear the windows shaking from the bass four blocks away.

Nelson: There was a seniors’ building directly adjacent, and when we played sound to the volume our crowd demanded it, that created problems.

Toronto vs New York

King Lou: Backstage were all these different people with abilities and powers, but nobody knowing how powerful or the possibilities of where they could go. Nobody knew the depth of the talent. Maestro would be there. Nobody was running around snapping pictures and recording things. It was all this talent going around, and nobody knew how to hone it.

Nelson: Hip-hop has always been mostly guys. Motion was representing [for women] back in the day. D-Shan, Fly K, Mischievous C, Cool K from Kilowatt sound system.

Berry: Michie’s secret weapon in a battle was to start breaking down to dancehall or reggae because the Americans wouldn’t do that. The DJ would change the music from a hip-hop to a dancehall beat and the crowd would go berserk. [The song] Jamaican Funk sounds the way it does because it came out of the concept of battling.

Michie Mee: When we did our set, the reggae would be so prominent you could hear the transition even louder through the system. You’d feel that the reggae bass was different than hip-hop. It added another layer. So I was a female rapper, number one, and then here we were with this reggae bass. The show was always full of energy.

Berry: The battles were the epitome of emotion because you had something to say. That’s where you had beef. That’s where you had your fight – through battle.

Michie Mee: The New York vs Toronto [battle] was the most famous event at the Concert Hall. There was nothing for the audience to gauge you by, so you had to entertain. The other female MC [Sugar Love] said – and this is online, too – “You want this bitch over here to win?” And the whole crowd said ,“Yeah!” I was just happy to get the recognition, to have won, to be a part of the scene and to still go on.

Winning at the Concert Hall really let them know I could battle any American. It let them know I’m Jamaican and I’m Canadian. There was nothing to fear. And female artists are here to stay – all from that one show.

Mistaboxx: Rumble & Strong [from Toronto] faced [the Bronx’s] Boogie Down Productions – KRS-One and Scott La Rock – the hottest group at the time.

Higgins: Strong was a DJ. He was an early turntable champion – a white guy. Rumble had a powerful voice, a powerful presence and Jamaican influence.

Mistaboxx: Toronto’s crowds have historically been fickle to their own. Rumble did a song called South Bronx Is Over, and it just blew up the place. He didn’t win, but I left thinking he should have.

Higgins: At Concert Hall you wanted to be as fly as New York. That meant adopting a faux New York accent and having your beats sounding like how they sounded in New York. The reason Michie Mee later got credit for Jamaican Funk was because it wasn’t so New York-centric. And then Dream Warriors did some jazz sampling. That’s when it felt like, okay, Canadian music is coming of age.

Kardinal Offishall: The first time I heard the [hip-hop/dancehall] mash-up was organically from Michie. That’s just a fact. Dream Warriors used to put it in certain songs as well. I don’t know if that’s the line in the sand that separated Toronto from New York. A bunch of American acts used to combine hip-hop and reggae as well, but that became the norm for Toronto.

B-Boy Destruction

Nelson: I was playing out all over the place and doing a lot of big events. Another promoter had an event at Flemingdon Park Community Centre and unfortunately afterwards a young man, Clinton Marshall, was chased down and murdered by a group of people who may or may not have been at that event.

People assumed it was my event so I got bad press. But instead of running and hiding and complaining, I took ahold of the situation. I invited the mother of the youth who passed away and the pastor who did the ceremony at the church to be part of the radio show. We talked about the violence in the community and afterwards I took it to another level and put out a record called B-Boy Destruction.

Berry: There was a time when there were just too many fights happening. Ron, as a promoter, felt that had to stop. He wrote a very long message – a rap – and we said, “Why don’t we record it?” So he came into Beat Factory Studios and we recorded it and I made a vinyl and we put it out.

Nelson: It spoke against violence in the community. If we don’t curb the problem and find solutions then we’re gonna lose the privilege of hip-hop that we have. My doors are getting rushed and the gangs were terrorizing my whole thing. Back then there was no therapy or groups to seek advice from. I had to do a lot of this stuff on my own.

Berry: Ron performed the song at Concert Hall.

Nelson: Boogie Down Productions were in the house and right after their performance I did this crazy dance. I had my hand between my legs and I’m feeling my crotch when I’m dancing and KRS-One came up to me and was like, “Yo, Ron, man! We gotta market that, man. That’s a crazy dance!” He had the “make money” look in his eyes. I didn’t take it seriously, but I still gave it my all.

King Lou: When you have a promoter who’s going to such lengths to actually keep the peace by performing, we all gave him a certain kind of respect. Like, maybe we better smarten up a little. Or take it outside or don’t do it. Don’t jeopardize this thing that’s going on.

Berry: The violence was because of other things – not music. Concert Hall was a congregation to celebrate hip-hop and there was a congregation of gangs at these concerts because that’s where the music lived.

Nelson: I remember the crowd was just mesmerized. They clapped afterwards, but it was like being in church almost. But they didn’t boo me.

Hip-hop goes mainstream

Nelson: I respect the rawness of hip-hop done in its skeletal form. We are against what the rock band stands for, which is the whole stage of production: guitars, keyboards and drums. We do it with one MC and one DJ. Rakim and Eric B. were great examples of that.

Ramos: One of the more memorable shows was Cypress Hill, Chubb Rock, Pete Rock and CL Smooth and the Fu-Schnickens. It wasn’t a real touring package deal back then. Ron had put it together, so it was Cypress Hill’s first show in Toronto. It was also rare to see so many acts together.

Mel Boogie (DJ/broadcaster): My older brother is Maestro, so I lived vicariously through him. One of the key concerts my brother did was opening for Big Daddy Kane on Christmas Eve in 1989, so when he came home after that show, I got the blow-by-blow account. I felt like I was missing out and I definitely was.

Motion: When Public Enemy came, I was part of the Unity Force, a Black youth organization. Ron would have us come up and speak to the crowd and address what was taking place in the city – whether it was police shootings of youth, different protests, riots on Yonge Street.

Mistaboxx: Everything was about having a good time, so when Public Enemy came out it was like, whoa, here’s a group that’s actually saying something and starting a movement. I’ll never forget that show because we were second row and probably the only two white dudes in the place. I remember looking around, being like, yo, this is intimidating, man.

Mannix: The Public Enemy show [in 1989] was different because it was the first hip-hop show at that venue that I went to that was not primarily Black.

Nelson: I promoted the way I usually did – exclusively to Black people except for NOW Magazine. I put an ad in and they did an article, as well. I had 1,100 people in attendance, but what shocked the hell out of me was that no more than 100 were Black. And this was Public Enemy, a conscious Black group designed to make Black people feel better about themselves.

King Lou: It was one of those concerts that had a lot of people who weren’t into hip-hop there – not just white people, but Black people who weren’t into hip-hop but were into equality.

Higgins: I noticed a bunch of multi-tattooed people wearing leather jackets with insignias. We were thinking at the time it was a bunch of white radicals.

Nelson: I didn’t understand why a guy came to me after the show and said, “Are you Ron Nelson?” I said, “Yeah.” And he handed me a cheque for $7,500. “What’s this?” He goes, “For T-shirts.” Every single white kid had bought a friggin T-shirt. Black people didn’t do that. We didn’t have that kind of money. That was the first realization to me that there was a brand new market. The reason it switched was because of music videos, I believe.

King Lou: Public Enemy were such a turning point in the world and in how we looked at ourselves. Public Enemy gave us a perspective of, like, c’mon, be better than what they think you are. Ron Nelson was constantly trying to keep that vibe alive at Concert Hall.

Motion: It was really great that, promoter-wise, we were seeing this type of recognition that all of these things – music, dance, education – were part of the culture.

Michie Mee: Ron was the common denominator between everybody. He was a DJ. He was the promoter. He had a studio. We depended on him. He was the one who gave us the confidence, specifically me, to be okay with who you are as an immigrant. And we both secretly liked rock ’n’ roll.

King Lou: When I leave the party and go home to Jane and Finch, 95 per cent of the people in the party I’m not going to see until another one comes up. So when we went [to Concert Hall], it became a new world.

Mistaboxx: After the show, everyone would walk down Yonge. It would be like a mob at 3 am. Everybody would stop at the Mac’s Milk that used to be right at College and Yonge and then walk down to the Queen streetcar. You would make friends or talk or go to the after hours.

Kardinal Offishall: By the time we went it wasn’t the same thing. We caught it on its way out. My first show there was Ghetto Concept and Brand Nubian. Just being there was dope. Once you got into the building, you could see all the stories come to life.

Nelson: I did it for as long as I could. It led to me have a reckless life. I was never employed fully. I was always self-employed for so many years and trying to make it on my own with my own financing. This was a tough journey.

Ramos: Ron had decided he didn’t want to do rap shows any more and started getting more into the reggae scene. The venue was used less and less. That was also a reflection of the industry growing up. When I started promoting shows in 93, you could do it in a [licensed] club. My first show was at the Opera House.

King Lou: It wasn’t that the Concert Hall was fading. We became aware of the rest of the world. You had the Internet. You had people travelling and getting into pagers and cellphones. The world just opened up and people from abroad could see what Toronto was like.

Samuel Engelking

MTV Canada and beyond

Brad Schwartz (president of Pop/former MTV Canada president): The history goes that somebody had bought the building and put together plans to turn it into condos, but they couldn’t get it approved by the city. So [former CTV CEO] Ivan Fecan went and bought it.

When CTV did the deal with Viacom to bring in MTV to Canada, it was like, oh my god, we have the perfect venue because this building was right downtown with a built-in concert hall.

Mannix: When it became a TV studio, that was a total mind-blow. It was like, “I can’t believe they turned this place into this.” It was cool, but not the same because the studio’s capacity was so much smaller than it was before.

Schwartz: When were getting ready to launch MTV Canada [in 2006], we needed to make a statement. We had spent a lot of time renovating that building so it could be an office but also renovating the Concert Hall to bring it back to its glory. We wanted to make a big splash.

I went to all the labels and said we need a big act to break in this venue and bring it back. Randy Lennox and Tony Szambor at Universal said Kanye West was on tour. We said to the team, “What does everybody think about Kanye West?” The response took, like, half a second. It was the quickest yes of any business meeting I’ve ever had – if we would be so lucky. And so they got him. He brought his orchestra and his DJ, A-Trak.

Mastermind: I started working for CTV Bell Media when they still owned the building. They threw a lot of corporate events, but they also did radio station events. I was in a group that performed at one of Ron’s Monster Jams when I was 15 or 16, so to host an event on the same stage years later was – I don’t want to say “surreal.” But it was a cool feeling.

Schwartz: Kanye came in the day before [the launch] and went through all the songs and visuals on the stage. He ran through everything himself to see how it played in the room. The night before the concert he fired his video guy, brought a new guy in, changed everything up and had everything fixed by morning. Some people could say, “What an asshole,” but I wish every artist was that dedicated to his craft.

Kardinal Offishall: I did the launch party for the Kardi Gras album at Concert Hall [in 2015]. We did a live, almost two-hour podcast about the history of Toronto upstairs, and the record release was on the main floor. I also had archivists scan flyers, blow them up and put them around the building. I wanted to bring those vibes into a modern time.

Higgins: Today, the venue scene in Toronto is a disaster when it comes to the live presentation of rap music as part of an extension of hip-hop culture. I’m talking small- to mid-sized, not the ones big American hip-hop acts play.

Mel Boogie: As a performer and an attendee, I can say a venue like Concert Hall is definitely needed today. There are so few stages that will take hip-hop bookings that actually have good acoustics and good staff. Most smallish hip-hop events are at either Mod Club or Revival. There are so few stages for performers to do their thing.

Kardinal Offishall: Hip-hop is woven into the fabric of our society now so it’s not really a big deal to keep up with the culture. In the Concert Hall era, you couldn’t passively be a fan. You had to make sure your antenna was in the right place, stand at a certain angle in the room and stay there just to be able to record some songs off the radio. Whenever I think of Concert Hall, I think of the passion that one had to have if they were involved in hip-hop.

Nelson: At Concert Hall, people in Toronto were able to see hip-hop live as if they were Americans going to shows in the U.S. at a time when the music was establishing itself. The Concert Hall separated Toronto from the rest of the country. The rest of the country did not have Ron Nelson doing hip-hop like a drug addict does drugs. Year after year after year, it became an integral part of people’s lives.

kevinr@nowtoronto.com | @kevinritchie