Architecture is one of those professions that everyone fancies him or herself an expert on, so test yourself. Check out these examples of facadism (visit them if you can – many will be open during Doors Open, May 28-29) and marvel at these relics of Toronto’s architectural heritage of all eras.

GIANTS OF FACADISM

Toronto Design Exchange (234 Bay)

The circa-1937 Toronto Stock Exchange building was sucked into the fourth “neo-Miesian” tower of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s TD Centre in 1983. Eleven years later it was restored and remodelled by Kuwabara Payne McKenna Blumberg Architects and reopened as the Design Exchange. Today its facade stands proud, like a flag, on a building enjoying a creative and intriguing retirement.

Concourse Building (100 Adelaide West)

Developers of the Concourse, completed in 1928 by architects Baldwin and Greene, knew back then that heritage attracts tenants, even when that heritage is new. Its ad read: “The Concourse Building introduces colour for the first time in downtown Toronto. The austerity of eternal grey which pervades our streets is relieved in this building with a lovely warmth of gold. An office in this building will be more than an office.”

Its replacement, the 40-storey Ernst & Young Tower, with “bits of the historic facade grafted onto it,” was labelled “facodomy” by the Star’s former urban affairs critic, Christopher Hume.

Harsh? Restoration architect Chris Borgal wants us to know that “the historic bits grafted on” are the entire two most ornate south and east faces of the Concourse building. Mosaics by J.E.H. MacDonald of the Group of Seven and his son Thoreau are preserved, as are geometric reliefs on the east side. Long-lost features will be replicated: stencils inside the lobby by Lawren Harris that were buried under layers of paint, vanished iron doors that will be reproduced from old photographs. Reconstruction is still partly hidden behind hoardings, but if you look up you’ll see the pinnacles at the top in their original splendour.

National Building (333 Bay)

Designed by Chapman and Oxley, architects of the Princes’ Gate at the CNE, the Sterling

Tower at Richmond and Bay and Sunny-side Bathing Pavilion, the National Building was dismantled in 2009 to allow construction of the 51-storey Bay Adelaide Centre West. Now its facade, also by Chris Borgal, is back, wrapped around the corner of Bay and Temperance. When asked about it by the Star, Borgal was sanguine about his work, which had to respect city decisions made before the 2005 amendments to the Ontario Heritage Act. “I took the attitude it was a done deal when I accepted the job, so… the objective was to preserve some ambience of the Bay Street canyon.”

HERITAGE FRAMED

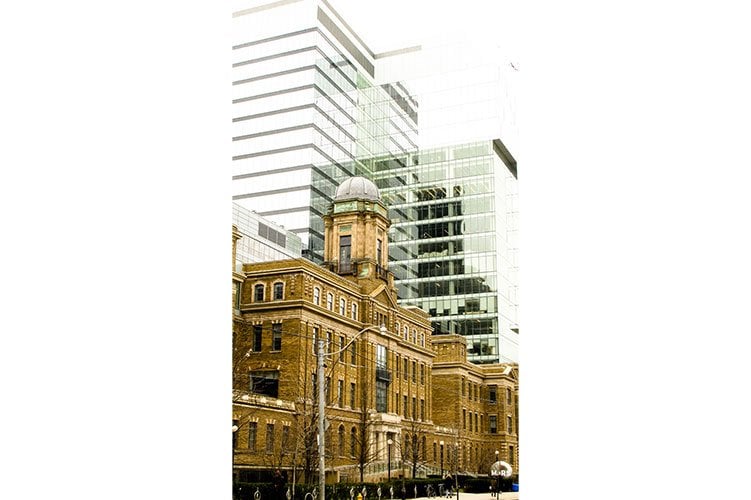

Toronto General Hospital, MaRS Discovery District (101 College)

Behind the facade of the third TGH building (conserved by the Ventin Group), the original atrium remains along with considerable depth of the original building that is now offices. Equally striking is the massing of MaRS. its glass towers bookend the hospital, rising to just eight storeys to the south, allowing the 1913 building to stand proud in its 21st-century glass frame.

dual HERITAGE

Bishop’s Block (192 Adelaide West)

One of “five upscale Georgian row houses” built in 1829 “for speculation” by Joseph Bishop, a butcher, it was home to author Anna Jameson. In the 1850s the block housed the Adelaide Hotel, and in the 1970s the Pretzel Bell Tavern. In 2007 the block was dismantled to allow construction of the 63-storey Shangri La Hotel. During excavations, Archaeological Services Inc. found a “complex process of construction, enlargement and demolition since the land patent was granted in 1801,” and objects that included children’s toys, writing slates, smoking pipes, glass and ceramics, some of which bore the stamp of Glover Harrison’s China Hall on nearby King West. It’s now Soho House, one of an international chain of members’ clubs.

CONSERVATION FRUSTRATION

Westinghouse Building (355 King West)

The Westinghouse Building’s Chicago-style construction, which was adopted after the great fire of 1871, depends on steel skeleton framing rather than load-bearing masonry walls and allows large window openings. Heritage Preservation Services recommended conservation of all four walls, with the building’s defining internal structure, but that was rejected by city council. The building’s steel framing has been removed, and only the two most prominent walls will be saved, to become the facade of a hotel at the base of a twin-towered, 48 and 44-storey condo, King Blue.

FORWARD-LOOKING facodomy

R.S. McLaughlin Building (832 Bay)

Dismantling for eventual reassembly is among the least-favoured of conservation options, but in the case of the 1925 neo-Gothic McLaughlin Building, the showroom of Canada’s first automobile company, it worked. The 48-storey Burano building is set back far enough to form a backdrop that resembles a waterfall behind the limestone jewel.

ALICE IN CONDOLAND

Tableau Condos (117 Peter Street)

The intimidating but impressive podium of the 36-storey Tableau tower at Richmond and Peter might have been inspired by the architecture of the age of great dictators: on its west flank is all that remains of its demolished predecessor, the art deco portico of 117 Peter Street that might serve as a peephole for Alice in Condoland.

sticker facadism

John Lyle Studio (1 Bedford)

Born in Ireland in 1872, John Lyle grew up in Canada to become one of Toronto’s leading architects, whose many landmarks include Union Station, the Royal Alexandra Theatre, Runnymede Public Library, the Dominion Bank at Yonge and Gerrard (now the Elephant & Castle pub), 11 Austin Terrace, (home of John Maclean, founder of Maclean’s magazine) and the Thornton-Smith building at 340 Yonge (now Champs Sports) that won him the Ontario Association of Architects Gold Medal in 1922. Between 1919 and 1943 his studio was located at 230 Bloor West. Today it’s facade, removed, rebuilt and reduced to a sticker on the face of the 32-storey Bedford condo, is all that remains.

John Kay & Co. Store (11 Adelaide West)

“One of Canada’s largest retailers of linoleums, carpets, rugs, draperies, wallpaper and furniture” was built in 1898. Its architect was Samuel G. Curry (also responsible for the Bank of Montreal that is now the Hockey Hall of Fame.) It was originally located at 36-38 King West and ended its life there as the office of Wood Gundy. When the building was demolished, its facade was dismantled and reassembled one block north, at 11 Adelaide West (on the site of the Grand Opera House that was owned by Ambrose Small, who vanished in 1919 and was never seen again.) The facade of John Kay’s store is now incorporated into Scotia Plaza, as the facade of Winners.

MICRO-FACADISM

John B. Reid House (24 Mercer Street)

Designed in 1857 by John Tully, for lawyer John B. Reid, it’s the sole historic survivor on what is now a bleak strip between Front and Wellington and John and Blue Jays Way. In 2012 the city rejected a plan to demolish 24 Mercer and replace it with a narrow 21-storey tower. The impasse was resolved by Scott Morris Architects, who will conserve the original first two storeys 24 Mercer’s facade while they demolish the dilapidated original structure behind it to allow the construction of three new floors of business space.

HISTORY ON THE MOVE

Commercial Bank of the Midland District, BCE Place

Architect William Thomas emigrated from England to Toronto in 1843. His many achievements through the remaining 16 years of his life include Brock’s monument at Queenston Heights and, in Toronto, St. Lawrence Hall, St. Michael’s Cathedral and the job that killed him, the Don Jail.

His first project was the Commercial Bank of the Midland District, built in 1844. It was dismantled and its facade reassembled in 1992 inside Santiago Calatrava’s Allen Lambert Galleria between Bay and Yonge. The Galleria’s soaring vault that enchants Torontonians is itself an example of facadism and, among purists, of structural “decadence.” Those lovely hyperbolic arches are entirely decorative the real work of roof support is done by the barely visible shallow steel arches above it.

APPLIQUÉ FACADISM

Royal Ontario Museum (100 Queen’s Park)

Facadism doesn’t always mean building new inside, behind or on top of heritage. Old buildings have been given new facades for centuries, not always with happy results. Storefront renewal has disfigured almost all of Toronto’s shops and businesses and, at the high end, there are more spectacular examples of “appliqué” facadism.

The original building of the Royal Ontario Museum, in Italianate neo-Romanesque style by architects Pearson and Darling, opened in 1914. It’s neo-Byzantine east wing, by Chapman and Oxley, opened in 1933. In 2007 the ROM acquired 100,000 square feet of new exhibition space, a new entrance and a new facade: Daniel Libeskind’s Michael Lee Chin Crystal. It also acquired an interior that still needs some figuring out and the kind of controversy that may last generations. But, love it or hate it, we cannot ignore the ROM, with its appliqué facade, and for a museum, being unignorable is rarely a bad thing.

Royal Canadian Military Institute (426 University)

Built in 1907, the building was deemed to be in such poor condition that there was no option but to trade it in when plans for a 26-storey condo were proposed for the site in 2007. The RCMI reopened in 2014 with a facade that replicates the original but made of new materials that make it look like a death mask.

HERITAGE mishap

Grand National Hotel (251 King East)

Where setback of new construction behind is not an option, the results for heritage preservation can be overwhelming.

GRAVEYARD OF LOST FACADES

Guild Park (201 Guildwood Parkway)

In 1914, General Charles Bickford built a manor house called Ranelagh Park on the Scarborough Bluffs. In 1932, Rosa and Spencer Clark bought it, renamed it Guildwood and made it the home of their arts and crafts collective. Starting in the 1950s, they began collecting fragments of Toronto buildings demolished during a modernist building boom, when there was little concern for heritage architecture.

Sixty years later, what is now Guild Park is a graveyard of Toronto’s architectural past. Fragments of lost facades include sculptures by Frances Loring, Florence Wyle and Jacobine Jones. Most impressive are the remains of the Bank of Toronto designed by Carrère & Hastings of New York, modelled on the Paris Bourse and completed at King and Bay in 1913.

In 1967 it was demolished to make way for the black towers of Mies van der Rohe’s TD Centre. At Guild Park the remains of the Bank of Toronto’s Corinthian columns and arches, with heads of Hercules in the skin of a lion, are reassembled into a Temple of Heaven that provides a stage for weddings and Shakespeare performances. Death with dignity, rebirth or reincarnation?

Richard Longley is past president of Architectural Conservancy Ontario.

news@nowtoronto.com | @nowtoronto