Pride Toronto has come a long way from the community-based committee that organized the first “Pride” festival and march that marked queer Toronto’s big coming out in 1981.

A lot has changed, including the version of history offered by the organization on its website as it celebrates 40 years. BLM-TO’s 2016 pause of the parade, for example, is nowhere to be found on Pride’s timeline. Other moments are missing, too. Like the shift of Pride festivities to the Gay Village in the early 80s and what that meant for BlPOC.

The origins of Toronto’s Pride movement go back further than the 80s, and though LGBTQ2S+ have fought and won many rights victories, there are still issues that remain outstanding and misunderstood today. Here are a few grassroots moments time forgot – and others worth remembering – as told by some of the artists and activists who were there.

We also want you to tell us the moments from Toronto Pride history that you think are important to remember. Email us at letters [at] nowtoronto [dot] com and we’ll publish a selection of responses – online and in the paper.

The first picnic celebrating Pride hits Hanlan’s Point (1971)

Before it became Toronto’s only clothing-optional beach, Hanlan’s Point was a notorious gay cruising ground, so it’s little surprise that it would play host to Toronto’s first unofficial picnic celebrating Pride. In her just-released book The Queer Evangelist, Cheri DiNovo recalls the emergence of a thriving gay scene in Toronto at the time and lesbian nightclubs masquerading as “Ladies’ Baseball Leagues” to avoid police raids.

The Body Politic is published (1971)

The monthly dedicated to queer self-determination was more than just a magazine – it was part of a movement. Run by a collective, it quickly gained a reputation for tackling controversial issues, including older men having sex with young boys.

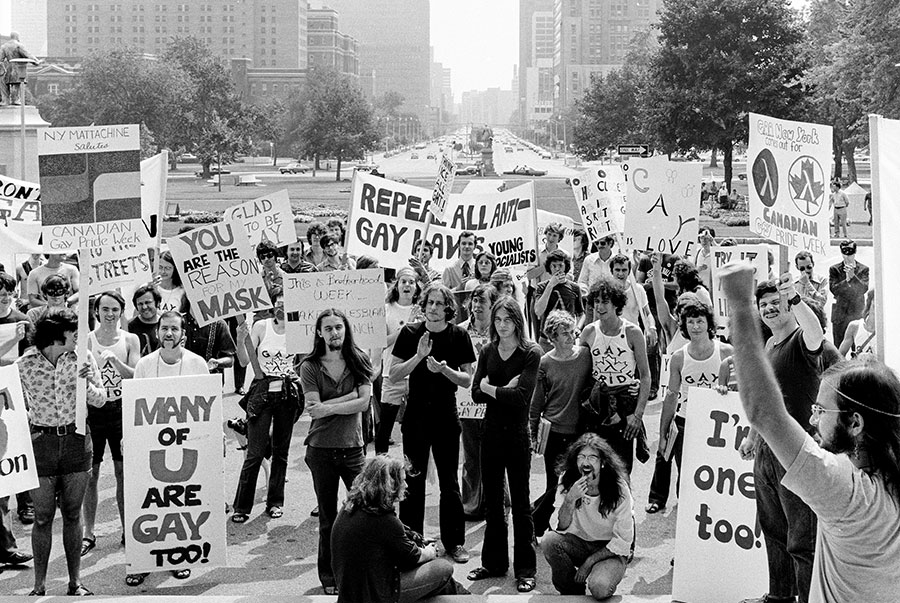

The first unofficial Pride march in Toronto (1972)

Pride Toronto was officially incorporated in 1981, according to its website. But the first Pride march in Canada, says author and activist Tim McCaskell, actually took place almost a decade earlier, in August 1972. It started at the new CHAT centre on Cecil Street, went over to Nathan Phillips Square and then up to Queen’s Park. McCaskell says the event was “to celebrate the We Demand demonstration in Ottawa held the year before, which in turn was timed to coincide with the promulgation of the decriminalization changes in 1969.”

The Criminal Law Amendment Act reforms to the Criminal Code decriminalized anal sex and gross indecency (broadly defined by police as oral sex), but only in “private” and involving two people over 21. Police used these and other laws, including the bawdy house law, to arrest gay people in public places – including parks, bars and bathhouses – for the next 40 years.

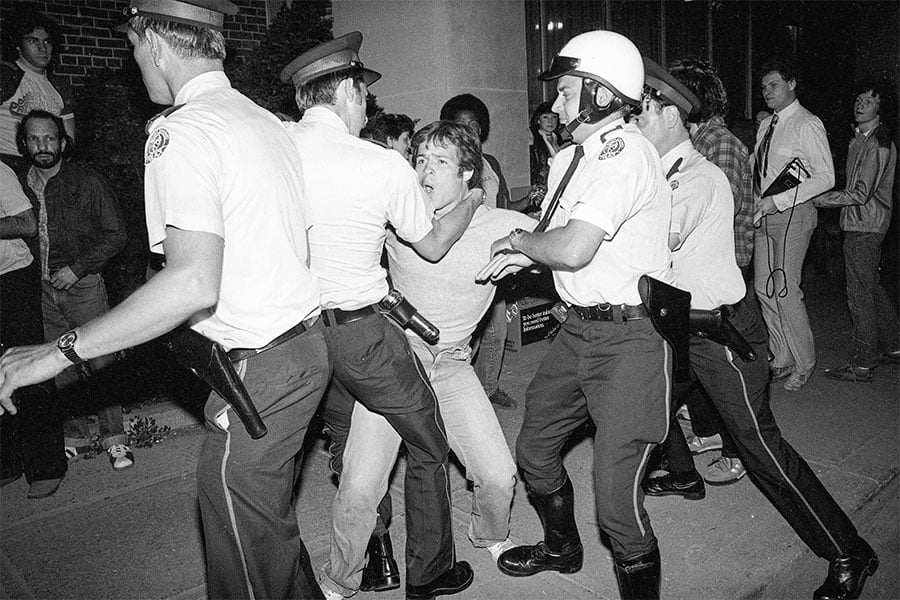

Bathhouse raids (1981)

The police called it Operation Soap, but when it was done it would also be known as one of the largest mass arrests in Canadian history at the time, second only to the mass arrests that followed the FLQ crisis in Quebec. A major demonstration closed down Yonge and Wellesley the next day. Barbara Hall, the future mayor of Toronto, was working for the law firm that was providing pro bono support for the “found-ins” arrested during the raids. The protest was not just a coming out for -LGBTQ communities in Toronto, Hall says “It was a learning of its strength.”

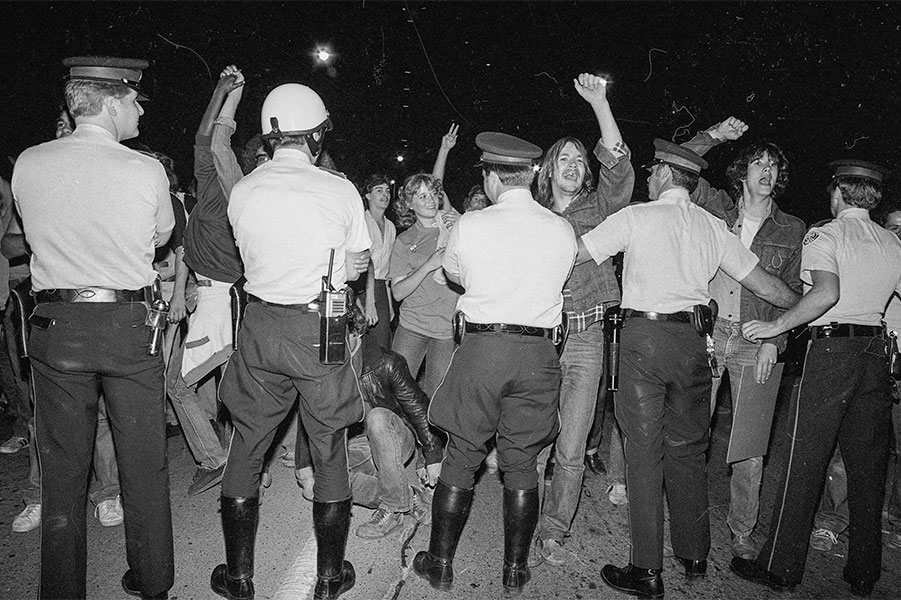

The battle of Church Street (1981)

“June 20, 1981 is a date that is often overlooked but is central to Pride Toronto’s founding,” says historian and York University professor Tom Hooper. “The police, even in the face of all this condemnation over the bathhouse raids in February 1981, doubled down on their attacks against the community. It was a police riot. Police showed up with billy clubs and drove a police car into the crowd, sending [The Body Politic editor] Ken Popert to hospital. The emergency room was full. The battles continued in the streets, and that extends to June 2016 when Black Lives Matter decided they were going to remind us of this history.”

The day 800 people chanted “Fuck You 52!” outside 52 Division (1981)

Gary Kinsman, who was actively involved in organizing with the Lesbian and Gay Pride Day Committee in 1981 and was the coordinating marshal for the June 28 march (Pride’s first), says Pride would not have happened without the mass resistance to the police that followed the bathhouse raids that brought LGBTQ- communities out onto the streets. It was a seminal moment. As Kinsman recalls in Radical Notes, “‘Fuck You 52!’ was very popular that year, along with ‘Enough is Enough!’ and ‘No More Shit!’’’

The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a “convent” of gay men who dressed as nuns “to target the moral conservative right-wing,” performed an exorcism of the police. More than 1,500 people gathered that day in Grange Park.

Pride festivities shift to the Gay Village and the beginning of Pride’s corporatization (1984)

Pride festivities moved to what was then called Cawthra Square Park. The group would take its first corporate sponsorship two years later. U of T professor Beverly Bain, a member of the No Pride In Policing Coalition, says “Pride became less political and more of a big party. The whitening, homonormativizing and pinkwashing of the Pride space made it difficult for Black, Indigenous and racialized queers and trans people to participate.”

Maggie’s Toronto Sex Worker’s Action Project is founded (1986)

Sex worker Peggy Miller and gay activist Danny Cockerline, formerly a writer for monthly gay magazine The Body Politic, among others, founded Maggie’s as a support network. The organization would become the first to acquire government funding to support sex workers with assistance, whether for emergency funds, harm reduction or drop-in spaces. Maggie’s organizer Ellie Ade Kur says that “There was a lot of overlap between street-based sex workers in the Downtown east and gay sex workers particularly in and around the village.”

AIDS Action Now! burns Jake Epp in effigy (1988)

Led by Michael Lynch, a long-time gay activist, writer and person living with HIV/AIDS, a meeting is held in the fall of 1987 to look at problems of medical access to drugs faced by people with HIV in Toronto. In May the following year, the group leads a demonstration on a national AIDS conference taking place in Toronto. Minister of Health Jake Epp is burned in effigy, making national news and putting the AIDS crisis on the federal agenda.

Pride gets its first parade Grand Marshals (1988)

Karen Andrews and Svend Robinson are named Pride’s first Grand Marshals. It’s 1988, and AIDS is on the rise. A temporary AIDS memorial is set up in Cawthra Park. Outside Toronto General Hospital, AIDS Action Now holds landmark demonstrations to protest drug trials that were delaying the release of lifesaving Pentamidine to AIDS patients.

Publication of Makeda Silvera’s book Silenced (1989)

Published in 1989, the Kingston, Jamaica-born novelist’s interviews with Caribbean domestic workers shone a light on a troubling chapter of Canada’s immigration system. Silvera would go on to cofound Sister Vision Press and edit Piece Of My Heart (1991), the first North American anthology of literature by lesbians of colour. Activist and educator Rinaldo Walcott says, “As a lesbian activist she wrote the most important work in that period on the fight for domestic workers to get landed immigration status.”

Toronto elects its first out gay councillor (1991)

Kyle Rae’s election marked a historical achievement in Toronto politics. But the first out lesbian councillor, Kristyn Wong-Tam, wouldn’t be elected until almost two decades later, in 2010. Wong-Tam notes that “Toronto is 187 years old and we’ve only had two out politicians during those years.”

City council proclaims Pride Day for the first time (1991)

Barbara Hall, who would become the first Toronto mayor to march in the parade years later, says “politicians were afraid to acknowledge the LGBTQ community. There was this sense of fear that it would destroy your political career. Back then church groups would organize protests along the parade route.” That same year, the Supreme Court rules that gays and lesbians cannot be excluded from entering the Canadian Forces.

Gay men banned from donating blood (1992)

In Canada, men and some trans people who have sex with men are banned from donating blood after thousands of Canadians become infected with HIV in a tainted blood scandal. It’s no longer a lifetime ban, but the rule still stands despite Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s promise to scrap it. Gay men are at a higher risk of HIV transmission, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada, but medical experts have called for a gender-neutral screening policy, arguing the chance of HIV getting into the blood supply is low.

So what’s the hold up? Trudeau’s government says Ottawa doesn’t have the legal authority to overturn the ban, but a federal judge recently disagreed. Years of legal wrangling in the human rights tribunal lay ahead unless the Liberals make good on their promise.

MPPs defeat Bill 167 recognizing same-sex spousal benefits in Ontario (1994)

NDP Premier Bob Rae puts the issue to a free vote, but after stating publicly that her party would support the bill, Liberal opposition leader Lynn McLeod flip-flops. Progressive Conservative leader Mike Harris opposed the bill.

The Toronto Rape Crisis Centre booth in the community fair (mid-90s)

The issue of gender violence arrives at Pride. Activist and educator Anna Willats remembers “painting people’s finger and toe nails in the colours of the rainbow as a fundraiser. Jack Layton spent part of his day painting people’s nails with us, one of many times he came out to support our work.”

Die-ins and kiss-ins: AIDS activism gets fierce (late 80s and early 90s)

Artist Luis Jacob recalls a time when gays and lesbians self-identified as “fags” and “dykes.” And artists like G.B. Jones and Bruce LaBruce railed against segregation of the sexes and veiled misogyny in queer spaces in their zine J.D.s, which helped spawn the homocore and later queercore movement.

“I remember attending a die-in protest organized by AIDS Action Now!” he says. “We gathered on Yonge Street – blocking traffic as we lay down on the pavement – to call attention to the AIDS epidemic the government and media refused to take seriously, because it was mostly ‘disposable’ people (homosexuals and intravenous-drug users) who were affected. I remember attending a kiss-in protest organized by Queer Nation.

“Having been alerted that the homophobic owners of a restaurant had recently kicked out a queer couple on a date, we took over the restaurant en masse – kissing and making out in front of all their clients – promising to return every day if they ever acted that way again. In response to the growing corporatization of the Pride Parade, I fondly remember the Queer Nation chant, ‘We’re here, we’re queer… we’re not going shopping!’”

We’re Funny That Way Festival has its coming out (1997)

Back in the mid-90s, it was acceptable for comics (usually guys, who dominated lineups) to take the mic and say “That’s so gay!” or call each other fags. Maggie Cassella’s festival featuring stand-up, sketch and character comics helped change all that.

Finding talent all over the continent, the fierce, fearless Cassella – who’s also a lawyer – introduced adoring crowds to a pre-Orange Is The New Black Lea DeLaria, iconic drag queen Christopher Peterson, homegrown fave Elvira Kurt and other legendary comics like Bob Smith and the Nellie Olesons.

The festival ran for 15 years, helping amplify the voices of future stars like Gavin Crawford, and returned in 2017 more diverse than ever, giving mic time to rising comics like Brandon Ash-Mohammed, whose Ethnic Rainbow show is one of many that continue to spread the word that queer comics can be funny any way.

Blockorama is born (1999)

The corporatization and homonormativizing of Pride turned a lot of BIPOC off. Blocko provided a safe space. Says Beverly Bain: “For those of us who struggled to find space in the Pride celebrations, this event brought back many of us and new BIPOC queers to the space.”

Mel Lastman brings his super-soaker to Pride (1999)

Lastman by most accounts didn’t want to march in the parade, but as the first mega-city mayor he was left with little political choice. He brings a distraction to the proceedings to ease him through – a giant soaker. Lastman gives as good as he gets.

Pussy Palace raid changes the face of Toronto policing (2000)

While the bathhouse raids helped set in motion a gay rights revolution in Toronto, the Pussy Palace raids carried out by cops less than 20 years later would change policing. As part of a settlement won by the Toronto Women’s Bathhouse Committee at the Ontario Human Rights Commission, the Toronto Police Service were required to enhance their efforts to recruit gay officers and adopt a “gender-sensitive” policy.

The Globe and Mail declares Pride parade okay (2001)

The Globe declares the Pride parade “a Canadian institution.” Another first: the city’s Official Proclamation of Pride Week includes bisexuals, transsexuals and transgender persons.

The founding of Trans Pride Toronto (2004) & Trans March (2009)

When Monica Forrester launched Trans Pride Toronto, the group became the first official trans contingency to march in the Pride Parade. Looking back, Forrester says trans people could finally feel like they were an integral part of something bigger. “That really changed people’s attitudes towards trans people – to recognize, yeah they are people and have a resilient community,” she says. Having worked for community agencies and having felt frustrated and silenced, Forrester started the collective of trans and Two Spirit people to offer more robust services, including counselling, outreach for people experiencing homelessness, and harm reduction.

Five years later, Karah Mathiason and Diane Grant started the Trans March, an unofficial Pride event that attracted around 100 people, and which has evolved into one of the largest of its kind in the world. In the future, Forrester wants to see trans people have more grassroots control over services and Pride events. “We see a lot of agencies getting money for trans health and trans programs, but when it comes to advocacy and standing up for the rights of trans people, they’re not doing that work,” she says. “If you look at the history of resistance it has been trans people who have been at the forefront to bring change.”

Legalization of gay marriage (2005)

Ontario and BC became the first provinces to recognize same-sex marriage in 2003, opening the door for the passage of the federal Civil Marriage Act in 2005. By the 2016 census, there were 72,880 declared same-sex couples in Canada.

The Blue Devil Posse makes its debut at Pride (2006)

The dance and performance troop organized by Natalie Wood to spread the message of justice in the Caribbean through the slave-era tradition of “Blue Deviling” arrives at Pride, inserting some Trinidad and Tobago Carnival spirit into the proceedings.

Pride puts up barriers along the parade route (2008)

“This added a huge layer of bureaucracy to its organizing and subtracted a huge layer of spontaneity that allowed people on the sidelines to tap into their inner queer and join the march,” says NOW contributing editor Susan G. Cole.

Cyndi Lauper’s True Colours tour headlines Pride (2008)

Pride’s first star-studded lineup features the B-52s, Rosie O’Donnell, Indigo Girls, and the Cliks. Former Spice Girl Melanie C performs on the main stage and Sandra Bernhardt hosts the annual Pride Toronto Gala and Awards.

Blockorama confronts Pride (2010)

After Pride Toronto moved Blockorama from the Wellesley parking lot to smaller locations around the Village, Blackness Yes! organizers had a meeting with Pride at the 519 Community Centre that resulted in the event returning home. By this point, the party was attracting thousands and booking buzzy local and international talent.

“That really changed the perception of Blocko to Pride and also our perceptions of ourselves,” says Blockorama DJ and team lead Craig Dominic. “It’s really cool to have a party and have people dancing but it’s even better when you see those people speaking up for you. Anyone can dance, but there’s a collective energy that comes from talking about how the work you do has affected their lives and the friends they’ve met there.”

The first Take Back The Dyke March (2010)

It was organized in protest to give lesbians more space, but it was also one of many demos and actions that eventually forced Pride to back down on the decision to ban use of the term “Israeli apartheid” at Pride events. It was an intense time in Toronto politics.

Toby’s Law enshrines “gender identity” and “gender expression” in the Ontario Human Rights Code (2012)

The landmark law championed by NDP MPP Cheri DiNovo – and named after Toby Dancer, a trans person who was street-involved when they walked into DiNovo’s Emmanuel Howard Park United Church looking for a meal one day – made Ontario the first jurisdiction in North America to recognize gender expression. Dancer died of an accidental overdose before the law was passed. They were buried in a mini-skirt under her trademark jeans. A stained-glass panel of Dancer playing piano adorns one wall of the church.

Kathleen Wynne becomes Ontario’s first out premier (2013)

When she came from third to win the Liberal leadership and become premier, it seemed that a new day had dawned in Ontario politics.

Not only would the new Liberal leader win the election that followed in 2014, she’d do it being open about her sexuality. “I don’t believe the people of Ontario judge their leaders on the basis of race, colour or sexual orientation – I don’t believe they hold that prejudice in their hearts,” Wynne said in her leadership acceptance speech. Only she would become the target of a right-wing vilification campaign that begat Doug Ford. There’s still a long way to go for women in politics, doubly so for those who happen to be gay.

Rising up against RadFems (2013)

Writer and activist Chanelle Gallant was among the women – both cis and trans – that rallied against the RadFem Rise Up! conference in Toronto. “The RadFems called sex workers, trans women and Two Spirit people ‘extreme terrorists,’” says Gallant, adding that the RadFems called the police twice on Toronto’s trans community and allies, falsely claiming they had made death threats. “We carried on and organized a public panel,” says Gallant, recalling the counter-event that brought together Métis artist and activist Mirha-Soleil Ross, Mohawk artist Aiyyana Maracle, the Eagle Woman Singerz and panelists micha cárdenas, Monica Forrester and Kim Katrin.

World Pride comes to Toronto (2014)

Toronto’s international place in the fight for gay rights is cemented when it becomes the first city in North America to host World Pride.

Black Lives Matter takes over Pride (2016)

The day BLM-Toronto turned activism as we know it on its head is not noted in Pride Toronto’s official timeline commemorating 40 years. How could anyone forget? BLM-TO, the year’s honoured group, halted the parade to make a list of demands. Most media focused on a call by BLM for an end to police floats at the parade. Some critics tried to argue that was “discriminatory.” But the demands were also about inclusivity in Pride as an organization. As BLM-TO co-founder Janaya Khan wrote in NOW, “We are not all on a level playing field fighting for the same equality.”

Pride adopts Black Lives Matter’s demands (2017)

Sex workers’ and prisoners’ rights activist Moka Dawkins calls BLM-TO’s action a pivotal and courageous moment for Black, queer, trans and non-binary people who organized it. “It was a very important moment of history for Toronto.

“We’re still taking to the street,” she says. “We realize that Black people have been suppressed for so long. We don’t ever acknowledge the strength that was put into removing these suppressive barriers.”

No Pride In Policing Coalition is formed (2017)

The No Pride in Policing Coalition, formed to back BLM-TO’s demands, led a rally at Nathan Phillips Square in June 2020 to demand the defunding and abolishing of police after the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. The global reckoning continues. On June 27 this year, NPPC will hold its second rally and march at Nathan Phillip Square.

The death of Alloura Wells (2017)

A defining issue for trans activists over the past two decades has been violence against trans people, particularly trans women. Trans Pride Toronto founder Monica Forrester has continually called for justice for murdered trans women, recently Alloura Wells, who was found dead in a ravine in June 2017.

“It is really frustrating that some three years later, not only is there is no justice for Alloura, there’s no answers as to how or why she died,” says Justin Ling, an investigative journalist and host of the CBC podcast The Village. “There’s no updates in the investigation. There was a thin apology from the Toronto Police Service, but nothing else. That’s galling to me.”

Bill C-66 doesn’t go far enough to expunge historical injustice (2018)

Bill C-66, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Expungement of Historically Unjust Convictions Act, took effect in 2018. Despite the RCMP identifying 9,000 potential cases, only nine criminal records have been expunged for either gross indecency (repealed in 1988) or buggery (renamed anal intercourse and repealed in 2018).

“Nine is a complete embarrassment. They need to overhaul their expungement legislation from the ground up,” says professor Tom Hooper, explaining the application process is restrictive, complicated and puts the onus on applicants to track down old documents. The law also doesn’t include people who were discharged.

“The discharge thing is important,” Hooper adds. “The purpose wasn’t to charge people with gross indecency and throw them in prison. The purpose was to charge them with gross indecency, humiliate the hell out of them and send them walking back home. A discharge meant nothing to the cops and prosecutors. They got what they wanted.”

Strapped is unleashed (2019)

The party catering to queer women and non-binary folks of colour was meant to be a one-off, says founder Marisa Grant. Two hundred people came out to what turned out to be the first event at the now shuttered Club 120, which had a leather-and-lingerie theme and became a monthly event that continued into the COVID-19 pandemic as an online event, collaborating with Club Quarantine.

COVID changes the game for queer bars (2020)

The COVID-19 pandemic led to the closure of long-running hotbeds of alternative queer music and culture, namely Club 120 and the Beaver. But while the fate of physical spaces to gather feels precarious, promoters got creative by shifting online. Pride Month, in particular, is a time of year that many queer artists rely on for income so the impetus to get creative online was extra real. Not only did Club Quarantine and Strapped became online staples during COVID, but Glad Day Bookshop and much of the city’s drag scene – growing in popularity thanks to Canada’s Drag Race – did the digital pivot to keep the tips coming in on Twitch.

The virtual strip club Strap House is founded (2020)

Started by Strapped and Maggie’s as a Halloween event featuring Black queer sex workers, it has evolved into something more permanent. “We just kept rolling it out month after month,” says founder Marisa Grant, “working with different Black queer women and trans folks to make them some virtual cash for shaking some virtual ass.” The Strap House has been collaborating with Pride Toronto – recently hosting a virtual porn festival – which founder Grant admits is a change from past years, when the Black queer and sex worker community have felt marginalized within the annual celebration. “When people think about queerness, it’s very white and it’s very cis.”

“Systemic discrimination” in Toronto police leads to failings in McArthur case

In April 2021, an independent review into the Toronto Police’s handling of missing-persons cases – including Tess Richey, Alloura Wells and the eight men serial killer Bruce McArthur pled guilty to murdering in 2018 – found systemic and “overt” bias led to missteps, including victims from marginalized communities receiving less priority.

Former judge Gloria Epstein found some officers had stereotypical ideas and misconceptions about LGBTQ2S+ people that impeded investigations and fostered mistrust between officers and community.

Journalist Justin Ling believes police will need to go further than Epstein’s recommendations and listen to community members, particularly trans sex workers, who say they are over-policed. “The community wants effective missing persons investigations. The community wants murders to get solved, but fundamentally they also want to be free from over-policing.”