The Brunswick House has been tamed, its floors no longer sticky with spilt beer, its walls no longer brown with nicotine. It’s as clean as it was the day it was born, ready for its new role – and for whatever the future might have in store for it.

Closed in 2015 following decades of conflict with a neighbourhood weary of after-hours madness, drunken fights and sidewalks pooled with vomit, the Brunny had its official reopening April 27 as a Rexall drugstore. What used to be Albert’s Hall upstairs, where jazz greats performed, will become a medical centre, and the third floor will be lawyers’ offices.

There is no denying that Rexall’s director of construction and design, Ricardo Reis, and Daniel Lewis of ERA Architects have done an excellent job restoring the building. Its original features can be seen now more clearly than ever.

A window that for decades was blocked has been reopened, chandeliers have been restored, the tavern’s barrel bar has been converted and behind it a mural of the Brunny’s history covers the wall.

Next fall, Heritage Toronto will mount a plaque to mark the building’s founding in 1874 by Benjamin Hinchcliffe, its rebuilding in 1908 by architect John Siddall (best known for his reconstruction of St. Lawrence Market in 1899 after it ceased to house City Hall) and some of the many talented people who made the Brunswick House famous.

But lovers of the cultural heritage of “Ye Olde Brunswick House” are shattered by its conversion. Some of them wondered for years if it could save itself by becoming the Drake or the Gladstone on Bloor. The hint was never taken.

• • •

Dorothy Willis, great-great-granddaughter of Brunswick House founder Benjamin Hinchcliffe.

One of the benefits of leading a Jane’s Walk is having people join you who know more about your neighbourhood than you do.

On the Harbord Village walk I led last year, I learned the location of the boyhood home of Joe Shuster, co-inventor of Superman. And I met Glenn Townley, who told me, “You should meet my cousin Dorothy.”

Dorothy Willis is a retired teacher who speaks proudly of intimidating schoolboy delinquents from her wheelchair. She’s the great-great-granddaughter of the founder of the Brunswick House, Benjamin Hinchcliffe. She and Townley share a prodigious trove of knowledge about the Brunswick House’s 140-year history.

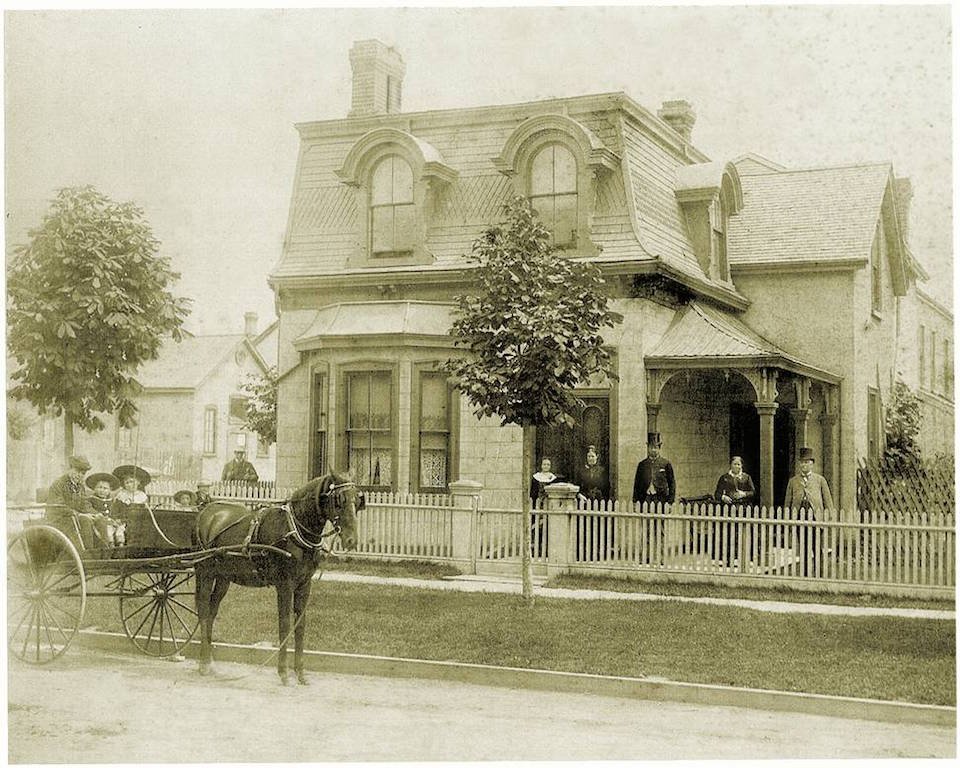

Benjamin Hinchcliffe, circa 1871

Hinchcliffe was born in 1831 in Silkstone, Yorkshire, England. In 1865 he emigrated to Toronto, where he managed a string of hotels, including St. George’s at Yonge and Richmond and the Osgoode House at Queen and York. In 1873 he sold two properties on Chestnut Street to finance his purchase of three pieces of land from Francis Skelton, an optician who lived on Adelaide West. These he assembled into a single 66-by-118-foot lot. It wouldn’t be named until two years later, but that’s where, in 1874, construction of the Brunswick Hotel began.

Its location was strategic.

Bloor Street (named for Joseph Bloore with an “e,” a brewer and one of the founders of the village of Yorkville) was at the edge of the city then, a wagon road that would be transformed in the 1880s by the building boom that created today’s Harbord Village to the south and the West Annex to the north.

There are no known illustrations of the original Brunswick House, but it was described in the assessment rolls as a two-storey, rough stone 15-by-30-foot building with a separate stable.

Among the hotel’s first clients were early immigrants to the area, labourers and wagoners who needed a place to eat, drink and stable their horses.

At times the taproom doubled as a ballroom, and when it was used for meetings it became “Hinchcliff’s Hall” (without the “e”). On August 23, 1880, Mayor James Beaty Jr. spoke there as Liberal-Conservative candidate in the coming West Toronto election.

The Brunswick Hotel seems an odd choice considering Beaty was a prohibitionist, almost as odd as his campaigning as a “Liberal-Conservative.” He won, though, and identified himself as a Conservative for the rest of his political life.

In 1882 Hinchcliffe moved his wife, Susan, and daughter Elizabeth one block west to an elegant house at 207 Borden, where he concentrated on becoming a successful realtor. In 1888 or 89, the hotel and stable were enlarged and sold to Emma Jury, wife of tailor Alfred Jury of Phoebe Street.

In 1907 Edward Jackson bought the property from the Jurys, and it was Jackson who commissioned architect John Wilson Siddall to design the Brunswick House we know today.

The new three-storey Brunswick Hotel with its large windows, moulded decorations and heavy cornice was a bold sign of the influx of wealth and development that had occurred since the hotel’s opening.

When Hinchliffe died in 1911, his assets were valued at $35,000, including the 19 houses he left to Elizabeth and her children. Value today? Almost as many millions.

With prosperity came honours. Hinchcliffe was a member of the St. George’s Society (headquartered at St. George’s Hall on Elm Street, now the Arts & Letters Club) and treasurer of the Sons of England Benevolent Society, which reckoned him “one of the most popular and well-known men who ever held office.” He is buried beside Susan in St. James Cemetery.

In 1920, the Brunswick Hotel was acquired by Kate Davidson, who renamed it “Ye Olde Brunswick House.” This was not the best of times to take over a tavern. The Ontario Temperance Act of 1916 allowed alcohol (that could be obtained with a doctor’s prescription) for personal use by guests in their rooms. It also allowed the serving in “standard hotels” of “light” beer to meet local “needs” and “demands.”

The maximum legal strength of “Fergie’s Foam” (named for then Premier Howard Ferguson) was 4.4 per cent, a problem for Davidson, who was fined several times for serving beer that was too strong. The Ontario Temperance Act was repealed in 1927, but drinking establishments remained famously gloomy.

The hangover of the temperance years ended at the Brunswick House in 1961, when it was taken over by Morris and Albert Nightingale. They turned it into a palace of hijinks, amateur and professional entertainment and enthusiastic drinking of famously cheap beer that sold in greater quantities than at any other establishment in Ontario.

Downstairs, Pickle Alley was the scene of pickle-eating contests, circus nights, a Mrs. Brunswick pageant for older women and entertainment by a cast of locals included Momma Chiklet (aka Mama Chicky), the Queen of Sweden, Carlos the Portuguese, One Tooth Juanita, Mr. Bones, Diamond Lil Shepherd, Ivy the Honky Tonk Queen and Donnie Sinclair, shoeshine boy, Elvis impersonator and occasional bouncer.

Queen of Pickle Alley was Irene Laviolette Aldrich – “Rockin’ Irene,” “Belle of the Brunswick House,” “Queen of the barroom torch singers” and former “Belle of the Silver Nugget Saloon” – who ruled from 1975 to 2002. Accompanied at the piano by Carla or Nate the Great, she shook her tambourine and belted out old songs for 27 years, opening with Julie Andrews ditties and closing with raunchy ballads like Roll Me Over In The Clover.

After she retired, Aldrich reminisced about the Brunswick House in the 1970s.

“The crowd was old. I mean old – if they went to the washroom they could drop dead in there. There were lots of fights, and the bouncers were untrained thugs. I had to control the room when I was on. It was like there were no rules – the crowd was just wild.”

Rockin’ Irene died in 2015, seven months before the Brunny.

• • •

In the late 70s, the Brunswick House stood in for the grubby Las Vegas nightclub Pete’s Place in the TV series Peter Appleyard Presents.

Upstairs, giants entertained among the regulars and one-night stands who performed at Albert’s Hall, “Home of the Blues” – among them: Blossom Dearie, Cab Calloway, Gordon Lightfoot, Oscar Peterson, Muddy Waters, Loretta Lynn, the Climax Jazz Band, Downchild, Blind John Davis, Dr. McJazz, Etta James, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Buddy Guy, Jeff Healey and k.d. lang.

Cover of 1975 book, Toronto, We Love You… “The Brunswick House” by Robert McInnis.

Witness to the shenanigans was artist Robert McInnis. In 1975 his drawings of musicians and barflies were published in the book Toronto, We Love You… The Brunswick House, with poems by Deborah Godin. Albert Nightingale was portrayed on the cover, gazing over his flock.

Forty years later, McInnis remembers his Brunswick years:

“I couldn’t afford models, but the downstairs tavern provided enough interesting folk. I sat and drew, filling a 100-page sketchbook in two weeks. Beer flowed generously. I’d trade a drawing to whomever I drew and then watch them fold it and put it in their back pocket or get it wet, spattered with beer.

“Yes, the Brunswick will be gone, but the great memories exist, as do the drawings. Albert’s Hall upstairs was a different place. Dixieland jazz. I was not into music. But, when [publisher] Simon & Pierre approached me to do the Brunswick book, I ventured there and found a whole new challenge, unlike the downstairs world, which was more suited to my temperament. Albert, the owner, often times provided me with a jug of beer as he presided over the place.”

Beer filled the lake in which the Brunswick House swam – $27 bought a tray loaded with 30 glasses.

But what goes down must come up – and down again. By 11 pm the men’s washrooms could be an inch deep in beer, with a lineup outside.

But love of the high life did not prevent Brunswickers enjoying more sober and occasionally more violent experiences.

There were literary evenings with Margaret Atwood and Irving Layton, celebrations of victories against the Spadina Expressway, singing of feminist anthems and, in 1969, Henry Ford and Nora St. John were wed by Salvation Army Major Arthur Shadgett.

Owner Albert Nightingale walked Nora down the aisle and said afterwards: “This is the first time I have ever willingly given a good customer away.”

Three weeks later, during a dispute over a woman, a man was shot in the lobby. Cal Kelly kept on playing – one man to calm the passengers of a sinking Titanic. It worked.

• • •

Samuel Engelking

Albert Nightingale’s run at the Brunny lasted from 1961 to 1975, when the Brunswick was famous for its wet T-shirt contests, and Molly ’n’ Me, Nightingale’s other venture, featured topless female servers.

In 1982, Nightingale’s inappropriate job interviewing techniques brought him before a board of inquiry that ordered him to pay $220 to the complainant for “loss of employment opportunity” and $100 for “mental distress.” He died six years later, aged 62.

But his departure wasn’t the end of the Brunswick House. Jordy Sharp, son of Four Seasons Hotels founder Issy Sharp, bought it in 1981.

He hired Derek Andrews to run Albert’s Hall.

“I was talent manager, booked artists, did publicity and oversaw all aspects of the music program – hundreds of acts over the five years, virtually all six-night engagements,” says Andrews.

“Jordy had a spirit of adventure and explored several musical directions, including his love of bluegrass. There were a few shows with Shox Johnson, but after Jordy hired me, we went after Eddie ‘Cleanhead’ Vinson and Junior Wells, icons of jazz and blues who helped establish early credibility, magic and a direction that continued for many years.

“We did a one-night stand with the late John Hartford that was a dream come true for him. The music critics at the Star identified me as their favourite flack several times. I promoted music that I could stand behind, and it was successful,” says Andrews. “But Jordy was restless and uninspired by the mundanities of running a big bar, so the building was sold to Joe Badali and Dennis Rawlinson, who had none of the vision or charm we’d seen in the early days.”

In 1986, Newsweek rated the Brunswick House one of the top 10 bars in the world. But in the years that followed, its clientele grew younger and louder. Some might have been the “busloads of innocents from the suburbs” described by Daniel, who’s sold books on the sidewalk outside the tavern since 2009 and lived until this month above the Tilt pinball parlour across the street.

Andrews is less kind.

“Downstairs was a vomit pit. While the Sharps had ethics and good taste, they couldn’t resist letting the wet T-shirt competitions continue. Downstairs was disgusting, while upstairs was bliss, musically.”

Slowly the Brunny sunk to little more than a booze can.

Albert’s Hall became Albert’s Parlor, a venue for off-track betting “located in the heart of the beautiful Annex in Downtown Toronto, with four tellers and 69 large televisions for your viewing pleasure, with televisions specifically set aside to satisfy all of your sports desires.”

And downstairs? By 2015, ClubCrawlers.com was posting scathing reviews:

• “This bar sucks!!! There were 30 people in the place last night. I had to pay 5 bucks to get in. You should be begging me to come inside. Who do I contact to get my money back?”

• “I don’t know what happened to this place over the last year. It’s become one of the worst bars in the city. The crowd is horrible, if there even is one! Security has no control. The staff and management are lost and have no idea what they are doing.”

• “I used to work for this establishment. It’s infested with cockroaches. We’d find them in the dishwasher, ice wells, in the corners of the bar mats, crawling up the pillars, on the lights. If customers complained about cockroaches in their drinks, we’d hand them a new one in hopes they would keep their mouth shut.”

And there were stabbings and shootings blamed on the Brunswick.

Tim Grant, former chair of Harbord Village Residents’ Association, was happy to bid the place farewell.

“While many people remember the Brunny’s golden years, when it was filled with university students and live musicians like Jeff Healey, in recent years police have been called constantly, and there was a regular spillover onto the street after the bar closed around 2 am.”

• • •

In 1985, Katherine Govier opened her short story collection Fables Of Brunswick Avenue with: “Everyone lives on Brunswick Avenue sooner or later.” Govier was never a Brunswick House regular, but she misses it and the great places that have closed on the Bloor strip in recent years: the Hungarian Castle, the Blue Cellar Room, Dooney’s, Book City and more recently Honest Ed’s. For the people who knew them, the loss of each one felt like a lobotomy.

Abbis Mahmoud, last proprietor of the Brunswick House, has his own regrets: “I want to thank the Brunny for all the great memories, all the good times, and for all the epic fights, the fights to reopen the Brunny and stay open against all odds.”

Mahmoud has since left Toronto to open the Moscow Tea Room in Ottawa. One of his cocktails is called Kalashnikov, but there’s no Rockin’ Irene and no topless waitresses.

Meanwhile, back in Toronto, Gus Sinclair, current chair of the Harbord Village Residents’ Association, who fought for years to temper the Brunswick House, has given the building’s owner, Larry Sdao, its Community Builder Award to thank him for persuading Mahmoud to break his lease – and allowing the beginning a new era in the Brunny’s long history.

With thanks to Dorothy Willis and Glenn Townley for their research into the Brunswick House during the Benjamin Hinchcliffe years, and Camille Bégin and Chris Bateman of Heritage Toronto.

Richard Longley is past president of Architectural Conservancy Ontario.

news@nowtoronto.com | @nowtoronto