Daniel Tate has been collecting classic Toronto concert ads and posters since 2015 on his nostalgia-triggering Instagram account, the Flyer Vault.

He’s spent most of the last half decade working his way through his collection of flyers, collected from his days as a teen raver and later as director of promotions for concert company REMG. But an insatiable desire to connect the dots of the city’s live music history sent him into the archives, sifting through microfiche and eventually linking up with music historian Rob Bowman (who wrote a cover story for NOW about Jackie Shane in 2017).

The two found common ground in their obsessive documentation of local music history and eventually decided to turn the Flyer Vault into a book – a ridiculously ambitious one.

“There are some good books about different Toronto scenes,” says Tate over the phone, highlighting Denise Benson’s club history Then & Now and the recent history of Toronto hardcore, Tomorrow Is Too Late. “But I think what really differentiates ours is the breadth of it. We’re not just specializing in one scene – we’re really trying to cover the gamut of all genres and sub-scenes that have sprouted up over the last century and a half.”

In an attempt to pinpoint the most important Toronto concerts, promoters and venues, The Flyer Vault: 150 Years Of Toronto Concert History (out now via Dundurn) is split into genre categories – from minstrel troupes to early rock and roll, classic rock, punk, hip-hop, rave, calypso and reggae, the Queen Street scene and more – each of which is traced from its earliest days until the cut-off point of 2000.

It’s also filled with flyers and first-hand accounts of classic concerts. Telling a fulsome history with both words and images led Tate to illustrator Dave Murray, who charts urban space with word maps. (You’ve probably seen his posters hanging in your urbanist friends’ apartments.) They commissioned him to create a map of Toronto music venues, and it jackets the book.

With the city in the midst of a venue crisis, Tate and Bowman felt it was important to highlight the impact of physical spaces on Toronto’s cultural history.

In back-to-back phone interviews, they picked a few of the most important venues in Toronto’s history and gave us a classic show flyer for each.

The Casino Club

Both Tate and Bowman chose this long-demolished venue first, mentioning it in the same breath as better-remembered (and still alive) venues like Massey Hall, El Mocambo and the Horseshoe Tavern.

The club, which stood around Queen and Bay, was most active in the 1940s and 1950s and was demolished in the early 60s to make way for the new city hall and Nathan Phillips Square.

“This was a time when Toronto was considered a lily-white, uptight, conservative city,” says Tate. “But right downtown there was this seedy little club, and it had everything. The [promoters] probably didn’t know it at the time, but they were bringing in the top American artists of the century, artists who have defined popular music.”

In the tradition of vaudeville, Casino would usually combine music and film, along with other performances.

“They’d have an amazing country show, then another week, a great jazz show, then R&B,” says Bowman. “Like, holy moly. They clearly had no genre policy but were just bringing whatever they thought was hip for a week at a time.”

An astounding list of musicians played there, from Dizzy Gillespie to Gene Vincent, Hazel Scott to Josh White. Tate gave us a 1950 flyer for Ella Fitzgerald, which bills her as “America’s first lady of song,” and for Johnny Cash, who made his Toronto debut in 1956 at the club with the Louvin Brothers, right around the same time he got his start at the Grand Ole Opry.

With Shea’s Hippodrome (a theatre that also hosted some legendary jazz concerts) basically next door, the area that now hosts Nathan Phillips Square was once a musical hot spot.

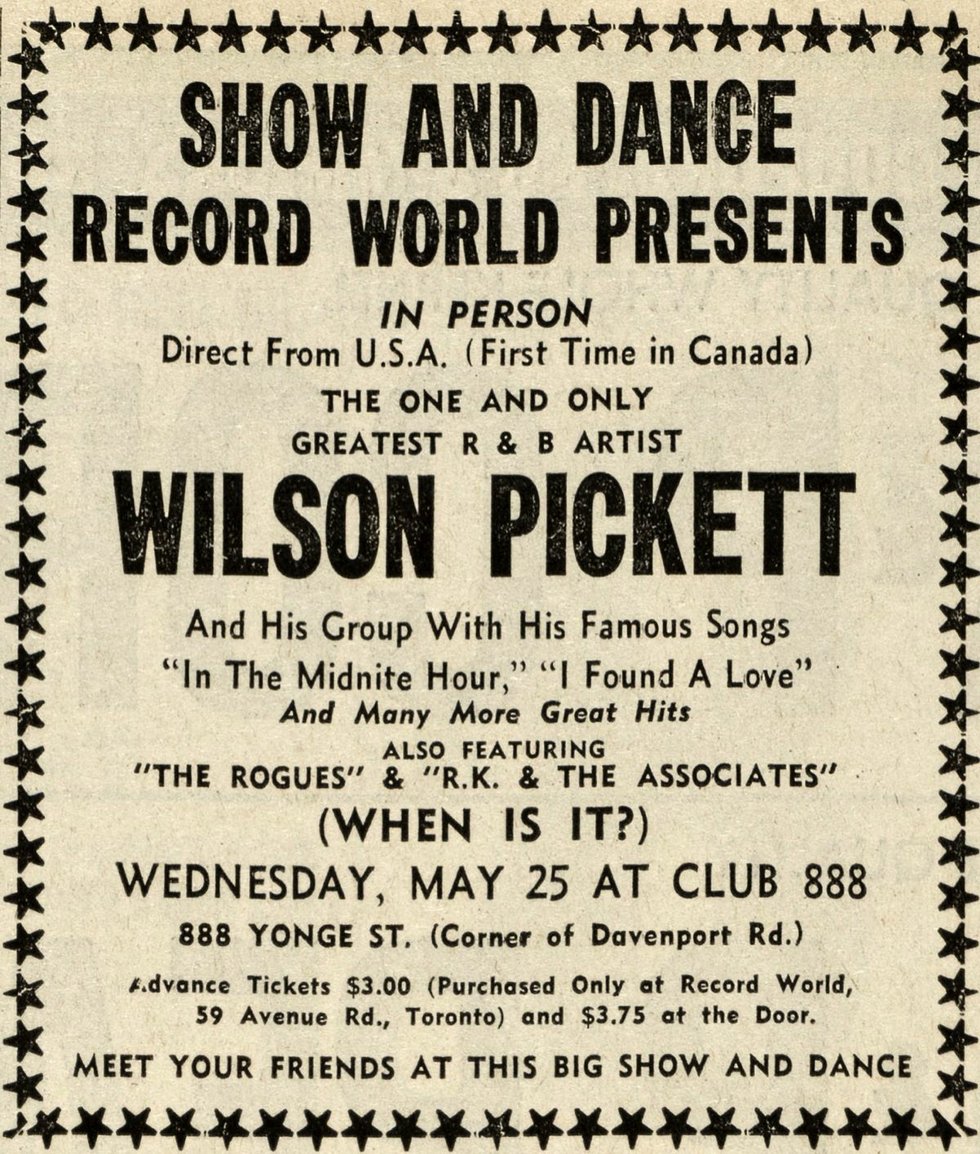

Wilson Pickett with an uncredited Jimi Hendrix at Club 888 (aka the Masonic Temple aka the Concert Hall) in 1966.

The Concert Hall

This venue at 888 Yonge, alternately known as the Concert Hall and the Masonic Temple, is now the office headquarters of Info-Tech, but it still hosts concerts over 100 years since it launched in 1918. That’s a minor miracle.

“It was very close to being demolished in 1997 to make way for a condo, and then it was saved by its heritage status,” Tate recalls. “I think we should be very thankful it wasn’t. That building is hallowed ground.”

The venue hosted the first demonstration of the then-new gramophone in 1918, so its legacy spans the entire history of popular recorded music. It’s hosted legendary concerts in almost every genre, from Motown to disco.

As the Rockpile in the late 60s, it attracted some of the biggest names in classic rock: Rod Stewart, The Who, The Grateful Dead, many, many others. Geddy Lee, who wrote the forward to the book, saw Led Zeppelin there and was inspired to start Rush. It’s now a Toronto Jazz Festival venue and even hosts events for the Hillsong mega-church.

But to Bowman, the biggest revelation was a Wilson Pickett show in 1966, when it was known as Club 888. While researching the book, he discovered the soul singer was supported by drummer Buddy Miles and a then-unknown Jimi Hendrix on guitar – something no other Hendrix scholars knew about.

“We had Hendrix authorities around the world telling us we were crazy,” he says. “But I found several people who saw the gig. A Black guitarist playing left-handed upside-down and played behind his back and with his teeth? Who else would it have been? And then I talked to Mike McKenna, who played in Luke and the Apostles, and he said all the guitarists were talking about it for weeks afterward. Then a year later when Hendrix was world-famous and playing here, they’re all going, ‘That’s the goddamn guy!’”

An ad for Rap Fest ’92 at the Concert Hall

As for Tate, the venue should be noted for its hip-hop legacy in the 80s and 90s, with DJ/promoter Ron Nelson at the helm – a period covered in our oral history in 2017.

“Today, Toronto is on the hip-hop map. But it wouldn’t be if it wasn’t for what Ron did at the Concert Hall.”

In the 80s, Tate notes, the venue became a de facto home for the city’s Jamaican and West Indian communities, putting on not just hip-hop but also legendary dancehall and reggae shows.

“Ron says in the book that a lot of venues just weren’t interested in hip-hop or were scared off or ignorant,” he says. “But the Concert Hall, not only were the acoustics amazing, but they had a very open embrace of music that other venues wouldn’t touch.”

Nash The Slash at the Edge

The Edge

Gary Topp and Gary Cormier, then collectively known as the Garys, were the punk promoters of the late 70s and early 80s. At venues like the New Yorker and a brief but explosive stint at the Horseshoe, they brought in some of the most vital punk and New Wave bands of the era.

“Gary Topp and Gary Cormier deserve the Order of Canada,” says Bowman. “What they did in terms of their programming and putting their own money on the line changed the culture of this city.”

From 1978 to 1981, after flaming out in spectacular fashion at the Shoe with the legendary punk concert The Last Pogo, they took up residence at a small Gerrard folk club called Edgerton’s and renamed it the Edge.

“It had terrible sightlines, the toilets leaked. The place was a pit in its own way, but, like a lot of places like that, this amazing scene formed around it.”

Bowman remembers a few formative shows: Pere Ubu, with lead singer David Thomas pounding a hammer on an anvil while playing Non-Alignment Pact lead singer Lux Interior hanging naked from the ceiling pipes during a show by the Cramps the Slits “with Ari Up’s hair done up looking like a pineapple.”

The venue had a restaurant licence so it was all-ages, and the Garys would purposely leave the doors unlocked during afternoon soundchecks so those in the know could come watch. And if the show was sold out, they’d set up speakers on the back patio and out front so you could hear it anyway.

“What other promoter has ever done that? What other venue has ever done that?”

A six-room blowout at the Guvernment in 2002.

The Guvernment

This harbourfront mega-club complex (originally known as RPM) hosted some of the city’s biggest electronic parties in its main venue and sub-venue the Warehouse (later called Kool Haus) until it was sold to developers and demolished in 2015.

Tate cites this “glorious playground” as one of his most formative venues, and he digs into it in the rave chapter but couldn’t go as deep as he would’ve liked due to the year 2000 cut-off. “To me, it was the club of the new millennium,” he says.

As one of the thousands of people dancing there from 1996 to 2015, he caught a ton of big rock and rap shows at the Guv: Oasis, Mac Miller, A Tribe Called Quest, Nas, Wu-Tang Clan, MF Doom. He was also a regular at the multi-room mega-raves Charles Khabouth used to host with DJs and producers like Tiesto, Armin Van Buuren and David Guetta.

Now, the space is home to the massive condo complex Daniels Waterfront – City of the Arts and its Artscape Daniels Launchpad arts complex, which houses the Imagination Catalyst, the Remix Project, Manifesto, the Weeknd’s creative incubator Hxouse and more.

But Tate is skeptical about putting Toronto’s cultural legacy in the hands of real estate developers, which is happening more and more – like with the Silver Dollar Room, whose heritage status means it will eventually be rebuilt within the Spadina condo complex that demolished it.

“But do the developers even know what the history is?” Tate asks. “Are they even adequately qualified to understand the impact of the influence that a particular building or piece of land had? Usually the answer is no. Because, frankly, developers don’t really give a shit about that kind of stuff. They care about maximizing profits. They’ll reach the sky, hand off the building to its new ownership and then take off to work on their next development.

“They’re not in the heritage game, they’re not in the history game, they’re not in the culture game. So when you make culture dependent on them, it’s a recipe for disaster.”

@trapunski