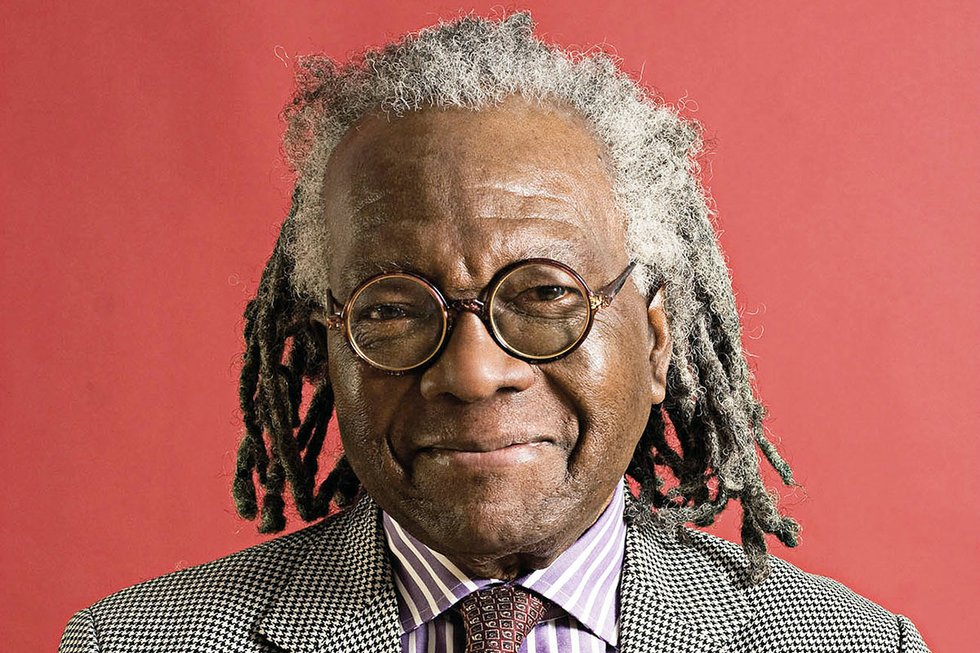

Shame on you if you’ve not read anything by Austin C. Clarke, who died last week. And double shame if you’re ignorant of Clarke’s damning insights into the economic basis of Canadian racialism.

I met Austin – “Tom” – Clarke for the first time in Montreal in May 1980, just after Quebec’s first sovereignty referendum. We were attending a Black Arts conference at McGill University, but he was the cool cat, with his pipe and books, emphatic smile and wily vocabulary. I was 20 and a tyro at writing he was 46, established and carefully cordial.

Austin was legendary for mentoring and being generous to other writers. After reading the manuscript and blurbing my first novel in 2004, Austin invited me round to the Grand Hotel where we – really, he – colonized the bar, ordering bottomless gin martinis (Bombay Sapphire), always with the obligatory triple olives.

Once 1 pm edged toward 5 pm, we retired to his digs on Shuter, where I was privileged to view the mementos of a momentous career while swilling the elite brandy that Austin decided my novel merited. Later, we taxied over to a King East watering hole where Austin ordered more martinis, fortified by hors d’oeuvres. When I left him there, finally, he was cucumber-cool, and I was foolish with drink. Even so, it was a terrific day and evening, and I was overjoyed to have spent it with a hero of my youth, a period when Austin was viewed by most – and saw himself, too – as Canada’s first (and only) Black writer.

Neither of those claims was true. When Austin published his first novel in 1964, his book appeared more than 70 years after Amelia E. Johnson published Clarence And Corinne, a Sunday school novel, in 1890. Nor was he utterly alone as a Black writer here in the 1960s: Haitian émigrés were writing and publishing in French in Montreal. But to the (white) Anglo-Canadian mind, Austin was “the only one.”

No one could be blamed for thinking so, not really. Clarke left Barbados for Canada in 1955, the very year Canada began to relax its negrophobic ban on “coloured” immigrants from the decolonizing world. He arrived at the forefront of a wave of Black and brown immigration that was to remake the old-school Black and Asian-Canadian populations.

Thus, Austin was a pioneer West Indian writer penning stories and essays about the dislocations faced by his protagonists, all easily based on his Caribbean compatriots and on the chilly Canucks who greeted their arrival here with disdain.

Although Austin matured very much as an Anglican in St. Matthias, near Bridgetown, Barbados, he was influenced by the Black nationalist views of Malcolm X and others in the late 1960s and became a one-man fomenter of Black studies programs at campuses from Yale to Duke.

But he was never able to shake his private school elitism or his love of the Latin and good grammar he associated with school and church, or his love of good suits and good drink that he associated with the WASP elite.

But that ability to hobnob with “the enemy” was what made his social critiques so scathing. Austin saw that Canuck racism wasn’t really only anti-Black or anti-Asian (or anti-Indigenous), but was rooted in what he called prepossessiveness: the idea that white Canadians’ ancestors stole everything, then set themselves up as judge and jury about who else was fit to receive some of the booty.

In other words, white Canuck racism was based not so much on allegations of inferiority, but on the fact that others came late to the looting and should be happy to accept and live on the leftovers.

Beyond the power of his fiction and the persuasiveness of his analyses, Austin was also vital as a symbol. He could have said, “Après moi, le déluge,” for it was after Austin, after his example, that so many other Black Canuck writers emerged: Cecil Foster and Esi Edugyan, Lawrence Hill and André Alexis, Dionne Brand and Althea Prince. Arguably, the entirety of contemporary African-Canadian writing is indebted to Austin’s trailblazing. He was our role model.

Now he is immortal.

George Elliott Clarke (no relation to Austin) is Canada’s seventh Parliamentary Poet Laureate. His latest novel is The Motorcyclist (HarperCollins) his latest verse collection is Gold (Gaspereau).

news@nowtoronto.com | @nowtoronto