In Toronto, there are places so mysterious, they might as well be invisible. And there are buildings in plain sight that contain unseen stories, histories, industries, businesses and ideas. For NOW’s third Hidden Toronto Issue, we spotlight 15 worth investigating.

1. JOHN SHELLEY TURNER’S TERRACOTTA JEWEL BOX, 20 Jerome

In the 1890s, 30 years before he began work on the Canadian War Memorial at Vimy, sculptor Walter Allward refined his skills by making moulds for decorative terracotta tiles at the Don Valley Brick Works.

In 1905, John Shelley Turner built 20 Jerome Street and covered it with terracotta tiles. The house was included in the book Terra Cotta: Artful Deceivers, by Alec Keefer, published by Architectural Conservancy Ontario in 1996. One hundred and thirteen years after it was built, the property has been deemed structurally unsound. Its destiny appears to be demolition. And its tiles?

The city, Ward 14 Councillor Gord Perks, the property’s new owners and its neighbours are determined that they be saved.

What will the fate of 20 Jerome Street be? The city’s Heritage Preservation Services (HPS) and the councillor’s office are interested in seeing if the remaining tiles can be showcased or reinstalled somewhere else in the community. An ideal location might be on Dundas, west of Keele, which is the Junction’s main street. Mary MacDonald, senior manager of HPS, says, “We understand how dear this building is to many in the neighbourhood and beyond, and we hope to find an honourable way to commemorate its loss.”

In the meantime, visit 20 Jerome Street and enjoy its beautiful eccentricity while you can.

2. WAR MEMORIALS OF HARBORD COLLEGIATE INSTITUTE, 286 Harbord

At Harbord Collegiate Institute, The Soldier, by sculptor George W. Hill, was dedicated in 1921 to honour “These former pupils who died for humanity in the Great War of 1914-1919.”

Steps to the east is a very different memorial, a sleek, stainless-steel sculpture in the form of a broken H, by Harbord alumnus Morton Katz. Unveiled in 2007, it reads: “To the boys of H.C.I., whose futures were taken in the Second World War, whose memories will be forever in Canada’s heart, this monument is dedicated.”

There are 52 names on the World War II memorial, more than half of them Jewish. There are 78 names on The Soldier, two of them of women. Hidden behind those names are amazing stories that have been researched by members of the Harbord Collegiate History Club.

Among those is the story of Lieutenant Daniel Galer Hagarty, the son of Harbord principal Edward William Hagarty, who toured Toronto high schools urging boys to join his “liquorless” 201 Battalion (in some cases with little regard for their age), until he lost his own son.

Daniel Hagarty was a student of civil engineering at the University of Toronto when he enlisted to fight at age 21 on May 13, 1915. He was killed at Sanctuary Wood, east of Ypres, Belgium, on June 2, 1916, while commanding No. 7 Platoon of the 2nd University Company of Princess Patricia’s Light Infantry. Only three of Hagarty’s platoon came out alive.

Three months later, when principal Hagarty resigned his commission and his 201st Battalion was disbanded, the response of his men was described in a letter by one soldier of the 161st Battalion to his mother: “I saw a mock funeral today up at the 201 Battalion. They are being split up tomorrow as they have less than 600 men. They dug a grave and buried a dummy representing their Colonel. They hated him, he was a whiskey soak, so on top of the grave they put a cross, a whiskey bottle, cig or some branches for flowers.”

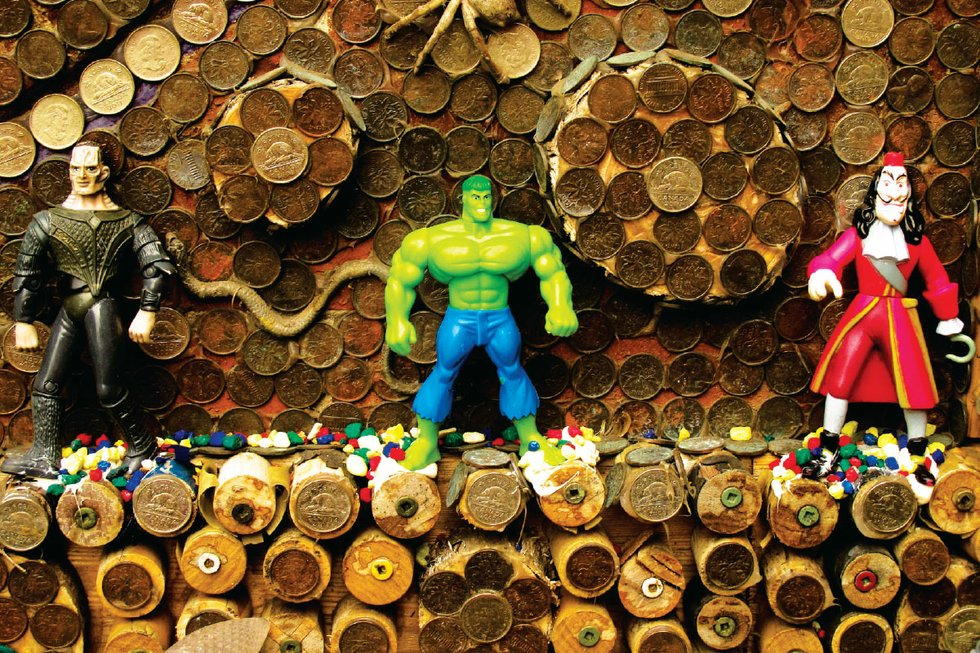

3. ALBINO CARREIRA’S ECCENTRIC GARDEN, 473 Clinton

In 1993, Albino Carreira fell from a scaffold, cracked his head on the way down and broke his neck when he landed on a steel I-beam. After two hours in a coma and 15 days in hospital he was discharged with a bone graft from his leg in his skull and nine screws to fix his neck. Since then he has worked to cover his house – front, sides, rear and his garage and van – with thousands of wood cylinders screwed in place to represent his vertebrae. He’s also decorated them with 180,000 one-cent coins (he has 30,000 more in his basement) and hundreds of toy figures “for the kids.” A certificate signed by former mayor Barbara Hall thanks him for creating the “best eccentric garden in Toronto.”

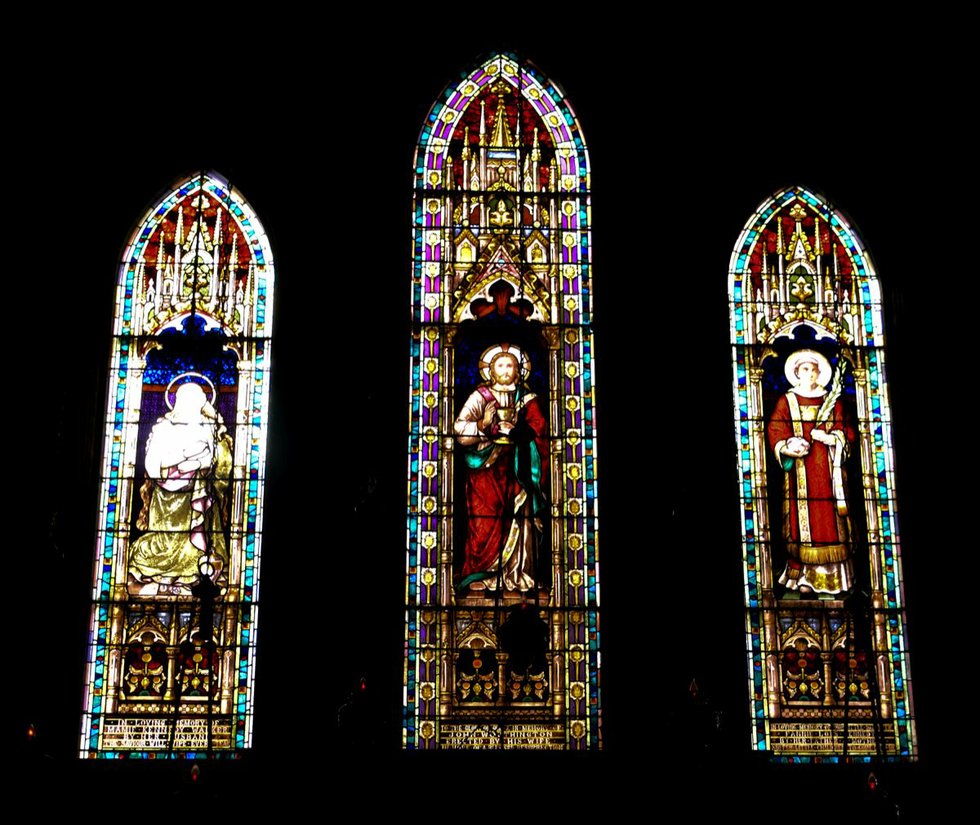

4. STAINED GLASS WINDOWS OF ST. STEPHEN-IN-THE-FIELDS, 103 Bellevue

Stained glass windows were the first lantern slides, the first use of light pouring through coloured glass to tell stories in pictures. In medieval times they were the “Bible of the poor.”

Eve Guinan Design and Restoration have been restoring stained glass windows for 33 years. In their workshop in an old industrial building at Lansdowne and Bloor, Guinan and her team have restored the windows of the University of Toronto Newman Chapel, Osgoode Hall, Holy Trinity, St. Michael’s Cathedral and have been commissioned to restore the windows at Massey Hall.

They’ll also be restoring the windows of St. Stephen’s-in-the-Fields that was “in the fields” when it was built in 1858 west of what would become Kensington Market.

The church that is now famous for being a “poor church that is a caring church with services for the homeless” was restored in 1890 by Eden Smith with stained glass windows by Nathaniel Theodore Lyon, which have since fallen into disrepair.

Heritage Toronto has promised up to $75,000 of the $150,000 cost of the restoration if St. Stephen’s can raise the same amount. Rector Maggie Helwig will be pleased to receive donations at saintstephens.ca.

5. JUNCTION SHUL, 56 Maria, THE FIRST NARAYEVER SYNAGOGUE, 187 Brunswick

Toronto’s oldest purpose-built synagogue, designed by local architect James Ellis and decorated by craftsmen from the nearby Heintzman piano factory, began services in 1913. The Junction’s Jewish population is now mostly dispersed but, restored by Joey Tanenbaum and maintained by other congregants who attended the synagogue when they were kids, the Junction Shul still stands, ready for weddings bar mitzvahs and the annual Doors Open.

The First Narayever synagogue occupies a former Foresters’s Lodge that was built in 1890. It was founded in 1914 as a landsmanshaft, an association of Jews from the town of Narayivv in Galicia.

In the 1980s, services became gender egalitarian downstairs while upstairs they remained Orthodox. This situation prevailed until the Orthodox congregants could no longer sustain a minyan – the minimum number of males (10) over the age of 13 that needed to be present at a service.

Since then, the congregation has drawn so many new members its synagogue must expand or move. Expansion will require raising the 130-year-old building’s upper storey and reconstruction of the facade to allow installation of an elevator. That plan is now with the Ontario Municipal Board. If it’s accepted, the result will be a synagogue that will look almost wholly new. It’s the conservationist’s dilemma: which comes first, built or cultural heritage?

Many of Toronto’s more notable school buildings are in disrepair, and that’s worrying with a new premier bent on “efficiencies.”

6. LANSDOWNE JUNIOR PUBLIC SCHOOL, 33 Robert

The Toronto school board’s chief architect Frederick Etherington was determined to build schools of tomorrow for the children of the post-World War II baby boom. Between 1957 and 1962 he commissioned young British architect Peter Pennington to design 10 schools that would be in stark contrast to their impressive but intimidating predecessors.

They include the City Adult Learning Centre at Danforth and Broadview, Grace Street Public School that’s now École élémentaire Pierre Elliott Trudeau, and Davisville Public School that, in spite of a hard campaign to save it by Architectural Conservancy Ontario, seems doomed to demolition

Pennington was most proud of his coronet-shaped Lord Lansdowne, built in 1961, with its chimney of multicoloured bricks twirling like a candy cane. He used it to explain his design philosophy in Canadian Art in 1962. Under his interesting title, A Gay School For Children, Pennington wrote: “A school gives the designer an excuse to let his hair down, to join the wonderful world of children, to laugh at convention and forget about the tried and true principles of design. At Lansdowne we wanted to create a gay building, a happy school for children. We hope that by creating a school of unconventional shape and using bright colours and a certain flair, we might stimulate the children – and the staff as well.”

More than 50 years later, Pennington’s buildings excite the imagination. But Toronto’s schools are in disrepair. That’s worrying, with a province now bent on “efficiencies.”

7. TORONTO BOARD OF EDUCATION ADMINISTRATION BUILDINGS, 155 College, 263 McCaul

At the southeast corner of College and McCaul, University of Toronto Health Sciences building occupies what were once the administration offices of the Toronto school board. In May 1959, the original 1917 building by architect Charles Hartnoll Bishop was mounted on rails and dragged 40 metres south to make way for its modern successor. The job was made trickier by the board’s insistence that the move be done while its staff carried on working in the building. It was expected to take a week but the move, the biggest at that time in Canadian history, was completed in less than 24 hours.

Peter Dickinson’s Education Centre could not be more different from its predecessor. It dazzles almost 60 years old, it looks as modern as the day it was born. Hidden behind it Charles Bishop’s red-brick, beaux arts monster lurks, trapped in obscurity, dark and menacing as a jail.

8. BLOORDALE UNITED CHURCH, 4258 Bloor West

Sitting like a flying saucer in leafy Etobicoke, Bloordale United Church is far from hidden but it is an amazing surprise. Designed in 1960 by architect John Arthur Layng, its circular form appealed to the minister at that time, Reverend Thomas Head, who noted that “for the first three centuries, Christians gathered around the Lord’s Table, and in Bloordale it will be restored to its original form.”

The church’s interior is spectacular. Its 12 arch ribs of laminated Douglas fir (representing the 12 apostles) converge on a central lantern, which pours natural light down onto the communion table.

The floor slopes gently downward to allow every congregant a clear view of the table and of the raised pulpit behind it. There are no pews. Layng insisted on chairs of laminated teakwood to make the space as light and, in terms of materials, as coherent as possible. To prevent their moving about and making a racket, the legs of the chairs sit in holes in the concrete floor.

Like many works of architectural daring, Bloordale United Church has had its problems. Its original slender metal frame spire that “drew eyes up 20 metres to the cross on top of it” shook so much in high winds that it had to be removed and replaced by a bell-shaped lantern. Its original floor-to-ceiling windows also had to be raised because of flooding, and its exterior is now clad in white siding. But, almost 60 years after it was built, Bloordale remains a startling example of mid-20th-century modern architecture.

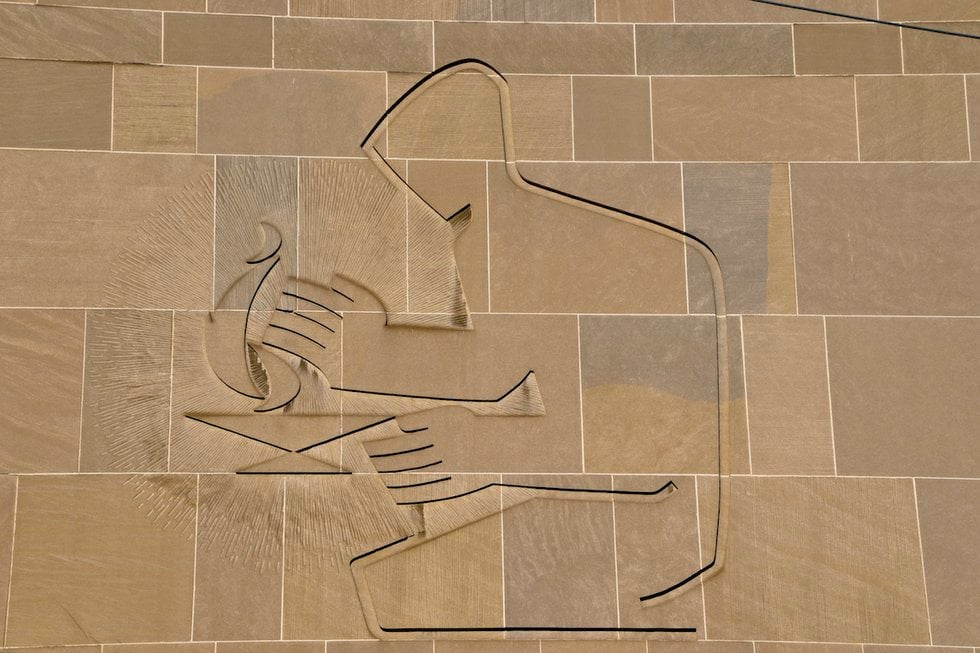

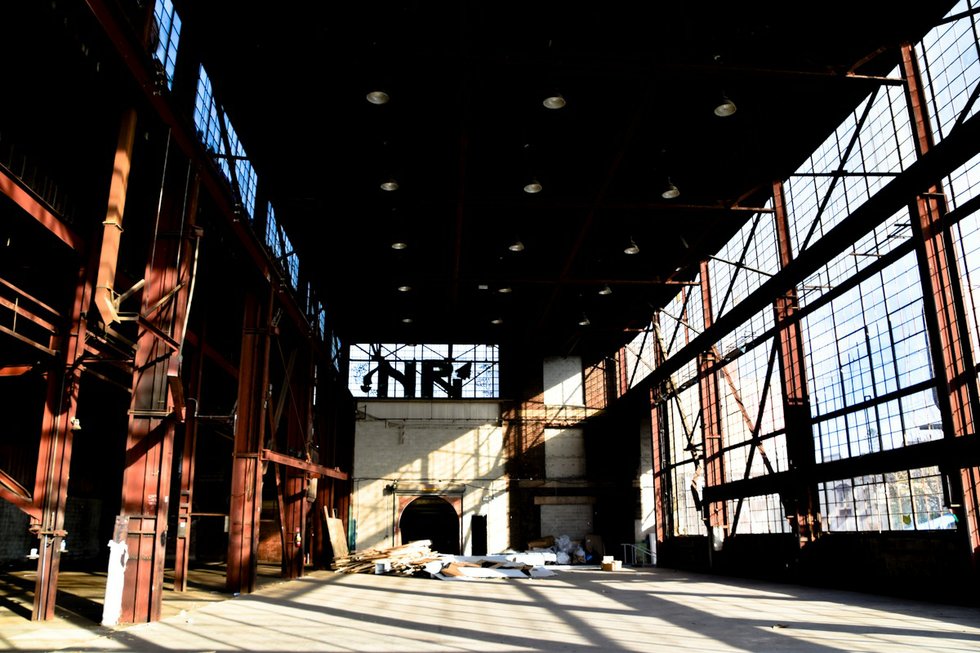

9. HAMILTON GEAR AND MACHINE COMPANY, 950 Dupont

This magnificent specimen of Miesian industrial beauty, which looks like it was cut off the TD Centre, has a muscular history. Founded in 1911, Hamilton Gear produced actuators that opened and closed the locks on the St. Lawrence Seaway, the pilot’s canopy of the Avro Arrow and sliding roof of the Rogers Centre (back when it was known as the SkyDome). Since Hamilton Gear vacated in 1994, the building has been moribund, many of its windows broken and covered with graffiti. Annexed to a furniture warehouse on an artery of Toronto’s former manufacturing heart, it languishes, its long-anticipated restoration and conversion into a Bellwoods brewery still up in the air.

10. WIZZ-BANG CORNER, 1909 Yonge

Today, the south wall of Starbucks at Yonge and Davisville is perfectly blank, a graffitist’s dream, but 100 years ago, in the summer of 1918, it presented a lively picture.

That’s when Stanley Francis Turner painted A War Record where he saw veterans of the First World War relaxing in the sun against the wall of what was then a store and post office.

The veterans, who were fitted with artificial limbs at the nearby North Toronto Military Hospital, nicknamed the corner “Wizz-Bang Corner,” after the scream and crack of the German artillery shells that deafened, maimed and killed so many during the First World War. A wizz-bang flew faster than sound. If Johnny Canuck heard one, it was already gone and he was okay. If he didn’t, he was likely done for.

In 1973 Jack Davis’s store was listed as heritage by the city. In 2013 Councillor Josh Matlow requested its designation under the Ontario Heritage Act. That has yet to happen, but the building’s remaining heritage features are well preserved by the building’s owners and by Starbucks. This year both parties were urged to sponsor a reproduction of Turner’s A War Record on the wall that was once Wizz-Bang Corner, but so far that has yet to happen. The painting is held in the vault of the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, where it can be seen by appointment only.

11. THE DOCTORS’ PARKETTE, Brunswick and College

Fourteen years after agitation began, the job is done. The Doctors’ Parkette, dedicated to honour the medical history of Harbord Village, whose stars include Norman Bethune and Henry Morgentaler, has transformed this once-squalid corner. A design competition announced by Harbord Village Residents’ Association in 2011 to revitalize the site produced 27 entries from eight countries. A panel of professionals judged them and residents voted for their favourites. Their choices, different but compatible, were combined beautifully and practically by landscape architect Henry Veenhoven. One cause of contention: should there be armrests on the benches so homeless people can sleep on them, or not? A compromise was reached to include armrests on some benches, but armrests were installed on all of them. No matter. They are so high, them and backpacks pushed against them can serve as pillows.

12. ST. CHARLES TAVERN, 484-488 Yonge

There was nothing saintly about St. Charles Tavern when it was opened in 1955 by Charles Hemstead, newsman-turned-real-estate-millionaire, horse breeder and winner of the King’s Plate. With its “Oriental Room” that served Canadian as well as Chinese food, the St. Charles drew guests from the Red Lion in the Westbury Hotel at Bay and College, which was better known to its gay clientele as the “Pink Pussy.” The Red Lion lacked the restaurant licence that allowed the St. Charles to avoid the 90-minute “dinner break” that Ontario liquor laws imposed on taverns until 1966. So, when the Red Lion took its break, its barflies moved north to St. Charles and there they stayed.

“Meet me under the Clock,” a reference to the tavern’s clock tower, was a summons for gay community events and cruising, but in those days it wasn’t easy.

At the Halloween “Call me Miss-Ter” revue, drag queens were pelted with eggs, in a city that was less appreciative of difference than it is today. After Hemstead died in 1961 the St. Charles stayed open until 1987, but upstairs a succession of discos and clubs – Empire, Time, Tower, Circus, Maygay, Charly’s and Y-Not – maintained its tradition until 1992.

Until this year, the remains of the St. Charles were imprisoned behind a facade of architectural dreck, but it’s about to get the Cinderella treatment. The almost 150-year-old clock tower has been cleared to allow its incorporation into the podium of a 38-storey condo tower named Halo Residences by architectsAlliance. The Halo, fronted by the St. Charles tower, will be (its brochure promises) “a new illuminating force in luxury” on a stretch of Yonge Street, between College and Bloor, designated a heritage conservation district and that presently boasts six payday loan shops plus the odd massage parlour and fortune-teller.

13. MASONIC TEMPLE CONCERT HALL, 888 Yonge

The Freemasons trace their lineage back to the stone carvers who built medieval cathedrals. Freemasonry was big in Toronto, and though grand masonic temples and lodges still dot the cityscape, most of them have been adapted to new uses. The six-storey Renaissance Revival Masonic Temple at Yonge and Davenport, built during the First World War, doubled as the Concert Hall, whose ballroom hosted Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, Tina Turner, the Ramones, Led Zeppelin and David Bowie.

In 2013 it was taken over by Info-Tech Research Group, which is “focused on building disruptive research and products that drive measurable results and save money.” Info-Tech has maintained the building’s most important heritage features and elsewhere installed offices named after past performers, graffiti walls and a spiral slide for whizzing down from the upper to lower level. It’s a fun place to work, a bizarre combination of brash 21st-century creativity in an envelope of early 20th-century conservatism – a combination that works.

14. BUILDING 191 at GUILD PARK AND GARDENS, 201 Guildwood Parkway, and a future RELIC PARK

Rosa Breithaupt Hewetson Clark was a woman born into wealth, who married wealth and who knew how to use wealth.

In 1917 she married Russell Hewetson of Brampton, who had been persuaded to leave his studies for the priesthood to rescue his family’s shoe business. After his death in 1928, Rosa tried to implement the co-operative ownership and profit-sharing she and Russell had developed together and bought Ranelagh, the 32-room home on the Scarborough Bluffs that Colonel Harold Bickford had built in 1914. It was there, in 1932, that she married Herbert Spencer Clark, who was 14 years her junior.

After honeymooning at Roycroft, the arts and crafts colony at East Aurora, New York, they founded the Guild of All Arts, a co-operative of artists and craftsmen who would share their lives and ideas and pay for their room and board with their works and labour. The co-operative attracted so many visitors, the Clarks added a dining room, gift shop and guest rooms.

During the building boom of the 1950s, 60s and 70s that gutted downtown Toronto of some of its finest architecture, they collected sizeable pieces of its great buildings to create at Guild Park a collection of sculptures, bas-reliefs, carvings, columns and decorative masonry that is now one of the city’s greatest assets.

At the edge of the woods, a few steps from the Guild Inn Estate, is Building 191, built in 1963 for office space and storage. It’s simple but beautiful, with a facade that includes a Margueretta stone from the Toronto Armoury, and bas-reliefs of naked, mounted warriors by Fred Winkler from the Globe and Mail building that was at King and Yonge between 1938 and 1974.

Building 191 will be renovated and expanded, to re-open in 2020 as the Clark Centre for the Arts. But before that can happen, the 900 or so sculptural fragments partly hidden in the vegetation must be removed. What’s to be done with them?

In the garden of Campbell House Museum at Queen and University, some of the finest pieces from the Guild Park stone yard are already displayed as part of exhibit “Lost & Found.”

Ralph Daley and Max Allen of the Grange Community Association have more ambitious plans. They are determined to create Relic Park, a zigzag of boulevards along back streets north of Campbell House toward Toronto police 52 Division and to the corner of the Art Gallery of Ontario on Dundas West.

In those boulevards they would erect monumental fragments from Guild Park and Gardens. In places close to the AGO and OCADU, where public art is strangely absent, it’s a brilliant idea.

Richard Longley is a former president of Architectural Conservancy Ontario.

news@nowtoronto.com | @nowtoronto

Infrastructure Ontario

Pit from 2015 archeological dig near Chestnut where 2,000-year-old spearhead was found.

15. A TOOL FROM ANOTHER TIME, behind former residence at 76 Chestnut

An astonishing and mysterious object appeared amidst the house remains and refuse thrown out by the immigrants who lived in The Ward. One hot day in the summer of 2015, archaeologists excavating the privy behind the former residence at 76 Chestnut Street recovered a 2,000-year-old spearhead from near the bottom of the pit. Made from a chert – a flint-like rock that outcrops along the north shore of Lake Erie between Fort Erie and the Grand River – this Indigenous tool is about 50 millimetres long and 28 millimetres wide. The archaeologists had no idea what it was doing in the privy.

While it is possible the projectile had been found elsewhere and brought into The Ward, it is far more likely that the piece had been discovered on the very lot on which the privy was situated. While now a sewer, the small stream known as Taddle Creek originally wound its way from its headwaters on the glacial Lake Iroquois shoreline near Wychwood Park southeastward through The Ward, to its mouth at Lake Ontario near the Distillery District. Its course across The Ward can be seen on the 1842 James Cane map of the city. But by the 1850s, it had been buried less than one hundred metres from the former location of the creek.

The proximity of the Armoury Street parking lot to the creek is important: almost all of the more than 18,000 Indigenous archaeological sites in Ontario are within a few hundred metres of water. While this is due mainly to the enduring necessity of potable drinking water for small camps and more extended communities, larger streams also facilitated travel by canoe and most water sources represented opportunities for fishing.

If we therefore assume the spearhead had been lost on that parcel of land originally, there are actually several mysteries here. How had the point been misplaced thousands of years ago? How had it been encountered in the 19th century? And why and when was it deposited in the privy?

One possible scenario to explain its original loss would be similar to the hypothesis developed for hundreds of other isolated projectile points found previously in Ontario – a hunting loss. Imagine, about 2,000 years ago, Indigenous hunters winding their way along the creek when, having spotted a large deer, they threw several spears at the animal. Fatally wounded, the deer ran along the stream, where one of the spear shafts and its stone point came loose and fell. When the hunters finally caught up with the animal, they removed their spears, only to find one missing. Having travelled a considerable distance, there was no chance to quickly find it. Besides, the party had more important work: butchering the animal and returning to their camp with the prized pieces of meat and hide.

Excerpted from The Ward Uncovered with permission of Coach House Books. All rights reserved.

The Ward Uncovered digs up the tales of a long-forgotten and much-maligned neighbourhood that was home to Toronto’s earliest Irish, Italian, Chinese, Jewish and Black Canadian communities using well-preserved artifacts unearthed during a 2015 dig of a Centre Avenue parking lot.

Ronald F. Williamson is an associate member of the Anthropology Graduate Faculty at the University of Toronto. He has published extensively on both Indigenous and early colonial Great Lakes history.

news@nowtoronto.com | @nowtoronto