After forming in Manchester in 1976, the Buzzcocks released three records in quick succession, the last of which was released in 1979 – the year I was born.

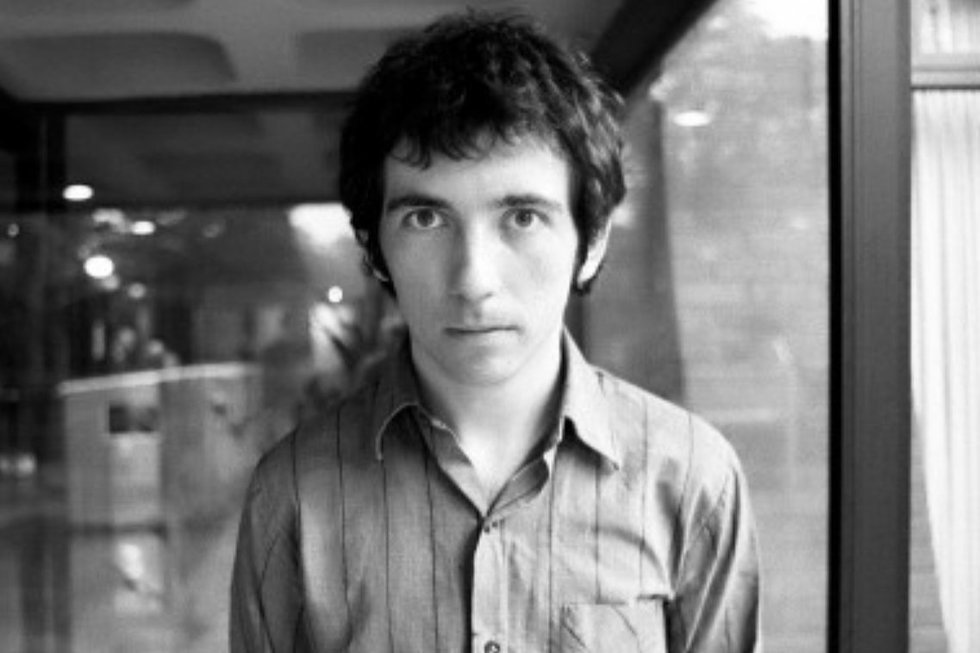

So as I sit writing this in the wake of lead singer and songwriter Pete Shelley’s untimely death this past weekend, it feels a little strange to be eulogizing a man’s career that I didn’t experience as it unfolded first hand. However, the effect his musical output had on me and so many others defies generations.

The Buzzcocks were central to the burgeoning punk and indie scene in the UK, but while their contemporaries the Sex Pistols and the Clash were railing against an antiquated dominant culture in snarling protest, Shelley’s songs were preoccupied with the idea of true human connection. He wrote about love, which was probably the punkest thing he could do at the time.

I truly discovered the Buzzcocks when I moved to the city. As a young closeted gay man growing up in a small town, falling in love with straight friends and the subsequent torment that coincided with it became a regular theme in my life. Pete’s songs articulated that queer desire that wasn’t translatable into my physical or emotional world, and validated those confusing feelings with his unique talent to channel giant ideas into perfectly crafted pop songs.

A certain amount of punk folklore exists believing many of these love songs were directed at Shelley’s bandmate, Steve Diggle, making lines like “it feels so real… so why can’t I touch it?” all the more heart-wrenching. As painful and isolating as unrequited love can be, Shelley framed the negativity with his remarkable, unrelenting wit. That skill is never as apparent as on the anthemic and definitive single, Ever Fallen In Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve) – a tune so flawless it will never age. Then on songs like You Say You Don’t Love Me, he shrugs off a rejection as if having become accustomed to unreciprocated romance, and even settles into the role, while maintaining a trademark wry, comedic twist:

“You say you don’t love me. / Well that’s alright with me cuz I’m in love with you, / And I wouldn’t want you doin’ things, you don’t want to do!”

Shelley’s direct influence is obvious, far and wide. You might even claim the pop-punk genre is his direct legacy. He certainly thought so. In an interview with NOW’s Tim Perlich in 2003, Shelley measured himself against bands like Blink-182 and the Offspring. “This whole ‘godfathers of punk’ thing is a bit strange, but I suppose that’s better than grandfathers of punk,” he said. “If I had my choice, I think I’d rather the Buzzcocks be known as the eccentric uncles of punk.”

His influence is unmistakable in equally iconic artists like Morrissey, whose own craft seemed to borrow heavily from Buzzcocks songs. It’s clear from the shared sardonic self-deprecation, to the way they tangled out conversations about sexuality and loneliness in their mutually simple but brilliantly avoidant poetry.

Shelley was ahead of his time in his use of gender-neutral pronouns in his songs. But it never felt coy or like he was hiding anything about himself, rather it seemed to only expand the universalism of his songs.

Shelley chose to remain vague about his sexuality, describing himself as fluid or bisexual. But the fact of his queerness, and his ability to navigate painful experiences with humour had a profound effect on my personal path of surviving those tricky years, as I’m sure it did for anyone who encountered his work, no matter their orientation.

In his post-Buzzcocks solo career, Shelley’s song Homosapien was banned in his home country for overt references to gay sex with lines like “Homo superior – in my interior!” – yet that song somehow became a top 10 hit in Canada. The inclusivity inherent in his punk origins allowed for these bold moves, and yet, depressingly in 2018, journalists still frequently rely on terms like “unapologetically queer” when describing LGBTQ artists, which suggests something to be ashamed of in the first place. That’s a disservice to the legacy and work Shelley did by remaining visibly queer long after the original punk scene he inhabited had passed.

Shelley’s queerness alone didn’t define him. More so, it was his effortless ability to navigate life’s many unrelenting heartbreaks by way of his distinctive twisted humour set to a perfect chorus that remains his greatest gift to us all.

I hope Pete found the love he was looking for. I know I haven’t, but thanks to Pete Shelley and the legacy he leaves in his songs, I do believe in it.